Martin Wolf is shrill (and rightly so). “Before now, I had never really understood how the 1930s could happen,” the Financial Times columnist wrote in an op-ed published on June 5.

“Now I do. All one needs are fragile economies, a rigid monetary regime, intense debate over what must be done, widespread belief that suffering is good, myopic politicians, an inability to co-operate and failure to stay ahead of events.”

Right on cue, the European Central Bank declined to cut interest rates, or announce any other policies that might help. Because what possible reason might there be to take action?

Survey data suggest that the euro area economy is really plunging now, plus Spain is on the brink. What about inflation? It’s falling fast — which is a bad thing under the circumstances.

I don’t think there’s any conceivable economic logic for the E.C.B.’s decision. It can only, I think, be understood as some kind of refusal to admit, even implicitly, that past decisions were wrong.

Like Mr. Wolf, I’m starting to see how the 1930s happened.

The Urge to Punish

I’ve been hearing various attempts to explain the E.C.B.’s utterly bizarre refusal to cut interest rates despite soaring unemployment, sliding inflation, and on top of all that the special problems of a monetary union that probably can’t survive unless overall demand is strong.

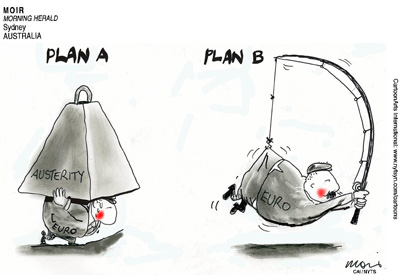

The most popular story seems to be that the E.C.B. wants to “hold politicians’ feet to the fire,” letting them know that they won’t get relief unless they do what’s necessary (whatever that is).

This really doesn’t make any sense. If we’re talking about enforcing austerity and wage cuts in the periphery, how much more incentive do these economies need?

If we’re talking about a broader fiscal union or something, what is it about the imminent collapse of the whole system that the Germans supposedly don’t understand?

Is there any conceivable way that cutting the repo rate by 50 basis points will somehow undermine actions that would otherwise happen?

What does make sense, maybe, is a two-part explanation.

First, the E.C.B. is unwilling to admit that its past policy, especially its past rate hikes, were a mistake.

Second — and this goes deeper — I suspect that we’re seeing the old Joseph Schumpeter “work of depressions” mentality: the notion that all the suffering going on somehow serves a necessary purpose and that it would be wrong to mitigate that suffering even slightly.

This doctrine has an undeniable emotional appeal for people who are themselves comfortable.

It’s also completely crazy given everything we’ve learned about economics these past 80 years.

But these are times of madness, dressed in good suits.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $44,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.