I’ve always viewed Spain, not Greece, as the quintessential euro crisis country. With Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy’s government balking — rightly — at further austerity, the focus is now where it arguably should have been all along.

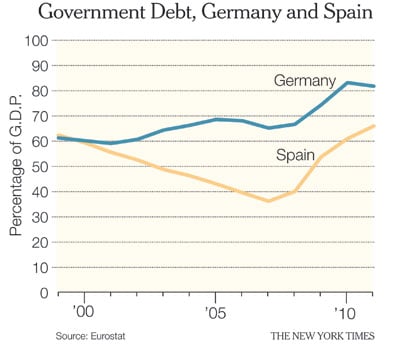

And with Spain now front and center, the essential wrongness of the whole European policy focus becomes totally apparent. Spain did not get into this crisis by being fiscally irresponsible; see the little comparison on the chart on this page.

And with Spain now front and center, the essential wrongness of the whole European policy focus becomes totally apparent. Spain did not get into this crisis by being fiscally irresponsible; see the little comparison on the chart on this page.

And while we say now that the surplus before the crisis was swollen by the bubble, Martin Wolf, a columnist at The Financial Times, points out that in real time the International Monetary Fund judged that surplus structural.

“Consider the structural fiscal positions for 2007, the last largely pre-crisis year, estimated by the International Monetary Fund in October 2007 — in ‘real time,’ as it were,” Mr. Wolf wrote in a column published on March 6. “This was a year when the indicator needed to scream ‘crisis.’ Yet it showed Spain with a large structural surplus and Ireland in structural balance.”

The question is what to do now. Clearly, Spain needs to become more competitive; maybe the labor market reforms it’s trying will do the trick, though I tend to be skeptical; otherwise it’s about gradual relative deflation — or euro exit and devaluation.

What’s clear is that even more austerity does nothing to help. All it does it reinforce the downward spiral, and bring the possibility of real catastrophe nearer.

Losing the Belt

A number of people have asked me for a quick, easy explanation of the difference between a government and a family — basically, what’s wrong with the argument that when times are tough, the government should tighten its belt.

I’m working on it. But maybe we can use Greece as a quick illustration of the point.

After all, you could view Greece as being like a family that overspent, got itself into debt, and whose members now have to do all the things families do when they get in that position: slash spending on inessentials, postpone medical care and other big expenses, quit their jobs and reduce their incomes — oh, wait.

That’s the key point, of course. When a family tightens its belt, it doesn’t put itself out of a job. When a government tightens its belt in a depressed economy, it puts lots of people out of jobs, and this is a negative even from the government’s own, narrowly fiscal point of view, since a shrinking economy means less revenue.

Now, you might argue that slashing government spending doesn’t actually cost jobs — that is, you might argue that if you had spent the past few years in a cave or a conservative think tank, cut off from any information about how austerity was working in practice. For the results of austerity policies in Europe have been as good a test as you ever get in macroeconomics, and without exception big cuts in government spending have been followed by big declines in gross domestic product. So lose the belt; it’s a really bad metaphor.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.