I did not write a critique of the movie Cesar Chavez when it first premiered because I felt somewhat conflicted, and I didn’t feel like jumping on a bandwagon. There appears to be a cottage industry of those who love to critique Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers (UFW) Movement, by people who have little first-hand knowledge of the events in question. From reading the many reviews, most of them seem to be formulaic, critiquing the movie as a hero-worshipping biopic, with deeply flawed acting, etc., etc.

Much of that critique comes from professional movie critics who know movies but who know little about Cesar Chavez and the UFW movement and know even less about the condition of farmworkers in this nation’s fields. Some of the critique is along the same lines as that of his former enemies, many of whom are from the extreme far right and who always equated him or saw him as an enemy of capitalism and an enemy of the state. Some criticism is from the so-called far left, some of which is simply hypercritical, not necessarily wrong, but seemingly unaware of Chavez’s larger role or value to society. Among these critiques, there is also valid and useful critique that comes from people with no ax to grind, primarily from human rights activists who lived that era or who are engaged in human rights struggles today.

What has been particularly troubling is that those who talk or write about the Chavez movie, almost never mention the conditions of farm workers today. It is within that context that I see/saw the movie. A 2007 book: The Farmworker’s Journey, by Dr. Ann Lopez, gives us a glance not simply into the conditions in the fields, but examines the deplorable conditions that force migrants from their homelands to migrate to the fields in the United States. NAFTA, a trade agreement that permits goods, capital and executives to flow freely back and forth, but not workers, continues to be the cause of that migration.

That the movie has failed to encourage a discussion regarding the current conditions of farmworkers is what I saw as its major drawback. Farmworkers today continue not simply to be exploited as in the past – in every respect possible – but also to be shamefully outside the 1935 National Labor Relations Act – a Congressional act that protects the rights of workers. They also continue to be inordinately exposed to cancer-causing pesticides. This should be the time to ask questions, but that has not really happened. Instead, the discussion is about whether the lead actor actually showed passion and whether the director actually understood who Chavez was, etc., etc.

Rather than focus on the lives of farmworkers, the movie appears to have been conceived as an opportunity to wax nostalgic or to rub shoulders with someone associated with the movie.

At the moment, farmworkers are also a primary focus of proposed immigration reform. The Senate (bipartisan) version of the farmworker proposals barely passes the smell test because it actually weakens the protections of the current “guest worker” (H2-A) programs. The House (Republican) version seeks a virtual return to the infamous Bracero program; workers are welcome, but not with any labor or human rights protections. Farmworker Justice provides a summary of these provisions.

The problem with the entire reform bill, however, is that whatever is eventually signed will unquestionably create a legalized underclass without many rights and protections for many years . . . until yet-to-be-agreed-upon provisions that will permit workers to begin their quest for citizenship kick in.

Writing about reality – whether in the past or present – versus a movie, is awkward. Like many from that era, I picketed and partook in many huelga actions, including boycotting lettuce, grapes and Gallo wines for many years and the sustained No on 22 and Yes on 14 legislative campaigns etc. I was also privy to the controversy surrounding Chavez, the UFW and the tension with the urban migrants’ rights movement.

All these campaigns have a story, and much of it, written in blood. A movie, justice cannot make. The real flaw of the movie is that it stops where it should have started; the 1970s was an intense period for the UFW, which saw many battles and even several deaths among its members. In one sense, it culminated with the 1975 California Agricultural Labor Relations Act.

When I first began to read the reviews prior to the premiere, I wanted to ask the critics: Did you ever picket for the UFW in the fields or in the cities? Do you know what it is to face right-wing mobs who hate everything about you and hate everything about farmworkers and everything that their movement stood for? Did you ever have to face riot sticks from law enforcement or intimidation by (anti-UFW) union goons? I would ask if they had ever worked in the fields, but that is unnecessary because the answer is already known and perhaps, at least for me, more important is whether they know about the conditions of farmworkers today.

That’s where the conversation should start and end.

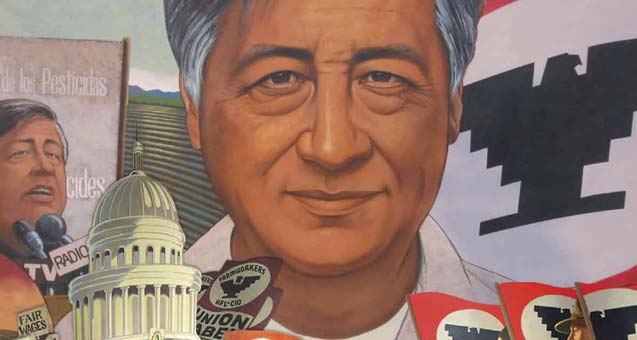

Realistically, unless one has many thousands of words, it would be difficult to meaningfully engage in any of the topics or campaigns mentioned above. Of course, the movie could have been better, in all respects. If anything, there is perhaps one topic that most critics missed and was not actually touched upon in the film. Chavez was never part of the Chicano Movement . . . and yet, for many, this brown man and all that he represented was its inspiration. Twenty years after his death, it is his name that is most associated with that movement and era.

I teach at the University of Arizon,a and my students have made the same observation about Ruben Salazar, the famed Los Angeles Times journalist who was killed by an LA Sheriff’s deputy on Aug 29, 1970. Neither was considered, nor did they consider themselves, to be part of the Chicano Movement, yet they are both viewed as historic icons of that movement.

That may explain why Chavez is held in the highest esteem by many from this community; in a community that has so few historic figures to look up to – because the history books and the media literally whitewash their history away – Chavez stands out.

I once told a harsh right-wing critic of Chavez – who masquerades as a progressive at times – that he knew very little about the inner workings of the UFW, and thus his criticisms were way off. Anyone with knowledge of the UFW could be even more critical toward Chavez and the union, but why? I still feel that way today. Anyone can criticize, but toward what end?

The one area where I never held back was the UFW’s policies regarding the migra (immigration police). Chavez always explained that the UFW policy had little to do with being anti-immigrant, but rather, with being anti-strike-breaker, often explaining that he would oppose his own mother if she were to cross a picket line. Many of his members, after all, he argued, were undocumented, so he wasn’t being anti-immigrant. Those of us in the migrant rights movement of that era were uncompromising about the issue. Labor leader Bert Corona, a giant in the history of the Mexican, Chicano and labor rights movement mediated, and things eventually got settled. It is true that after that, and to this day, Chavez is seen as someone who fought for the rights of all workers, especially migrants. One quote attributed to him and still in use today is: “The migra is the gestapo of the Mexican people.”

There is much more to tell. And many more books will most likely be written . . . perhaps about all the violence inflicted upon the UFW, the lives lost and all the interracial organizing that took place in the fields and in the picket lines.

Several other things need to be added. It was Dolores Huerta who created the concept of “Si Se Puede” (“We Can Do It”). That is a concept that even the president has “borrowed,” I believe, not always with attribution. There will be many books and hopefully many movies about Dolores Huerta one day. She has an incredibly powerful story to be told. But here, one last story about Chavez. I was present when this story was told to family members and close friends. One of the very last things Chavez spoke about right before he passed away was the need for the farm worker’s movement to align with American Indians. That was triggered when he read a book on the coffee table of the home where he was staying in Arizona. Right after that, he went to bed and did not wake up.

It is said that 50,000 people went to his funeral. I was there. I traveled over 1500 miles to be there. I saw the all-night vigils. It was a pilgrimage. Yes, he had many faults. But how do we choose to remember him? Solely for his faults – or for being part of a movement that permitted workers to raise their heads a little higher? Missing today are not heroes, but a mass movement that focuses on that same objective . . . of not simply improving the deplorable conditions in the fields in the 21st century, but also of bringing about dignity to the same workers and their children who daily put food on our tables.

The truth is, the movie indeed is a battle over memory. The question is, who should be in charge of telling that narrative: movie critics or people who actually took part in those historic struggles?

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.