C.L.R. James in Imperial Britain opens up the issue of the Third World struggle in an elegant and memorable way.

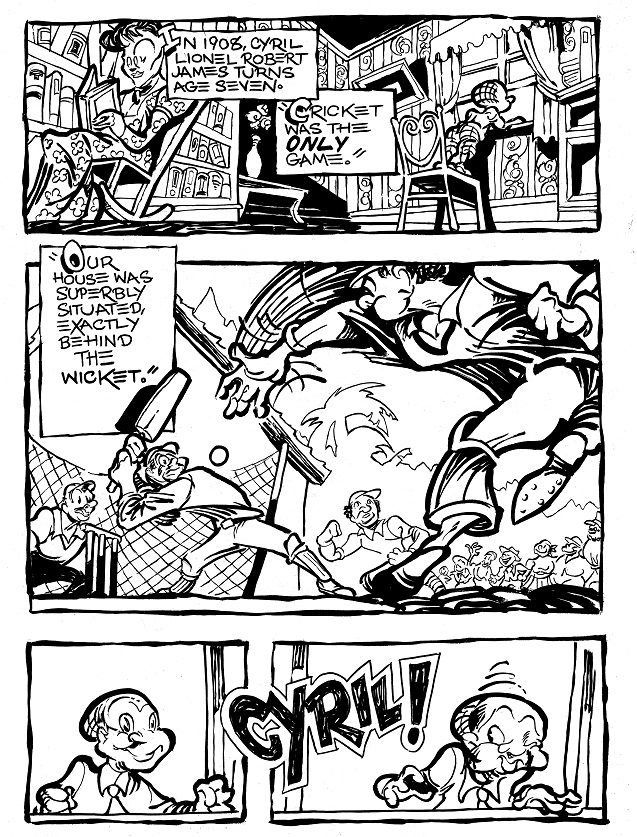

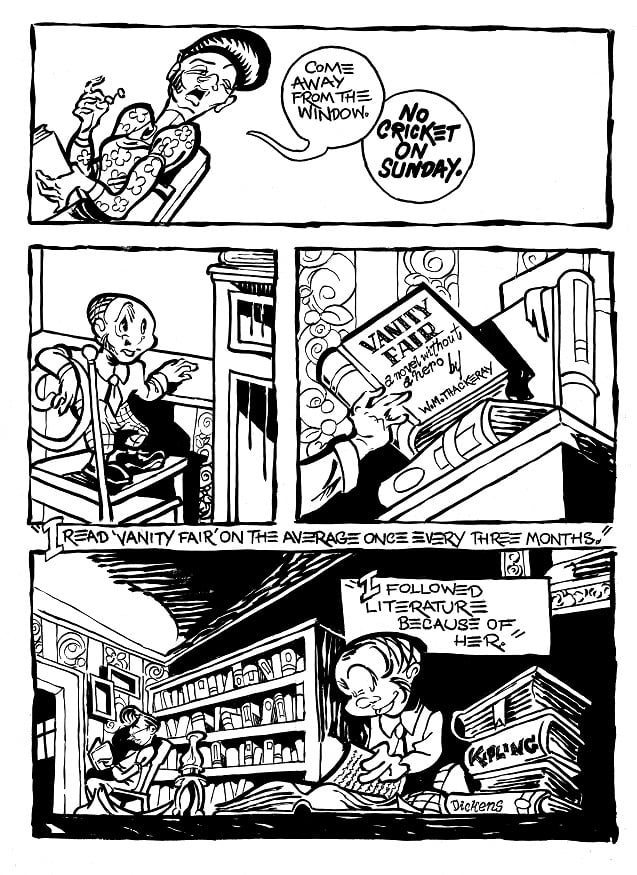

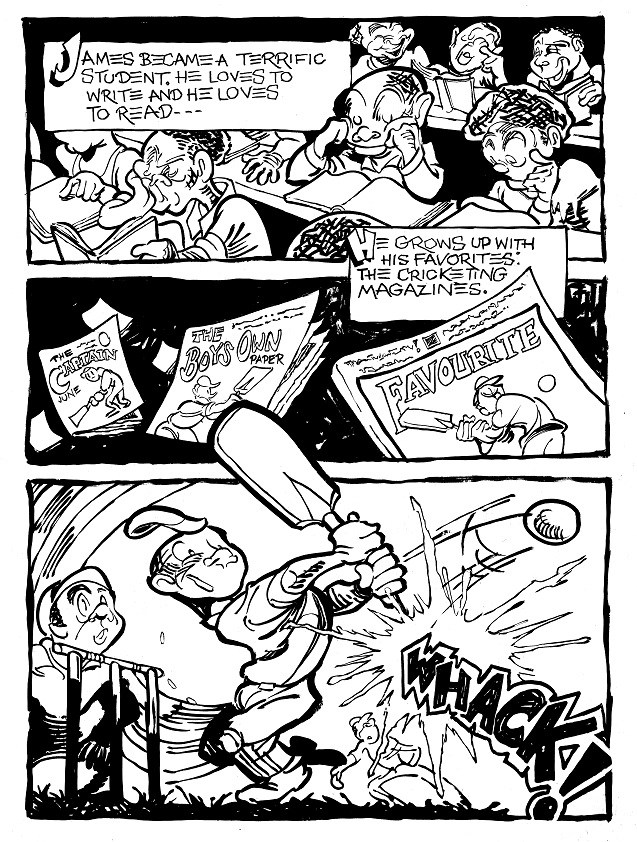

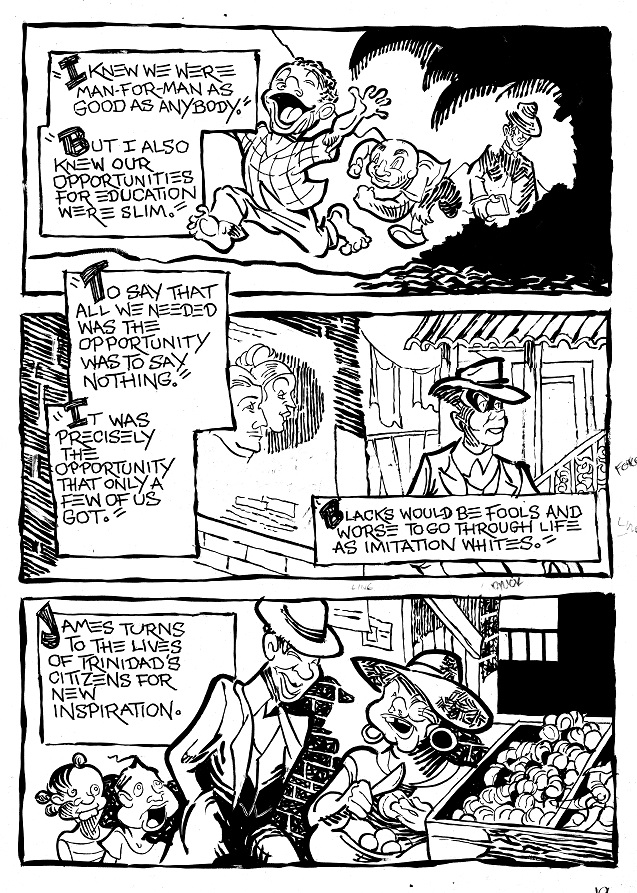

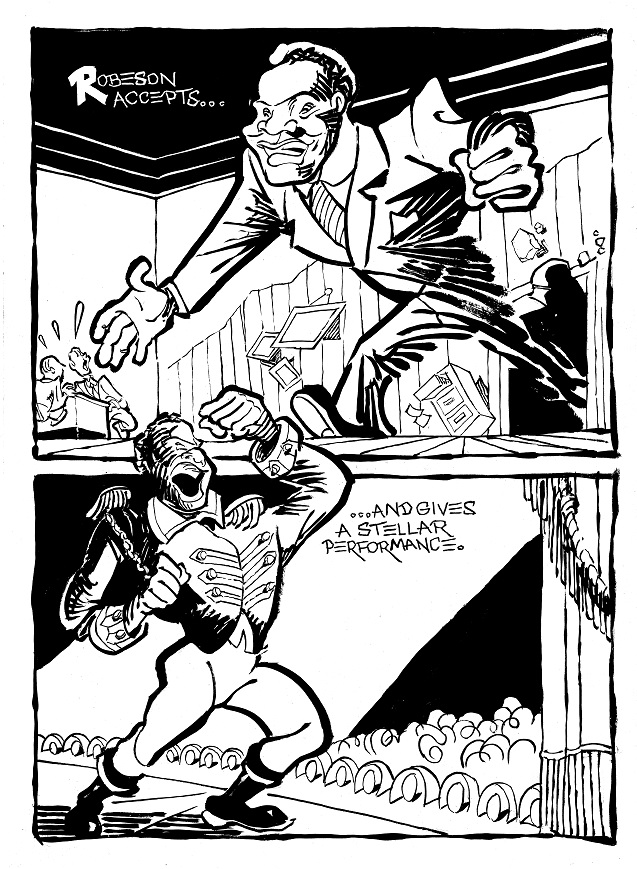

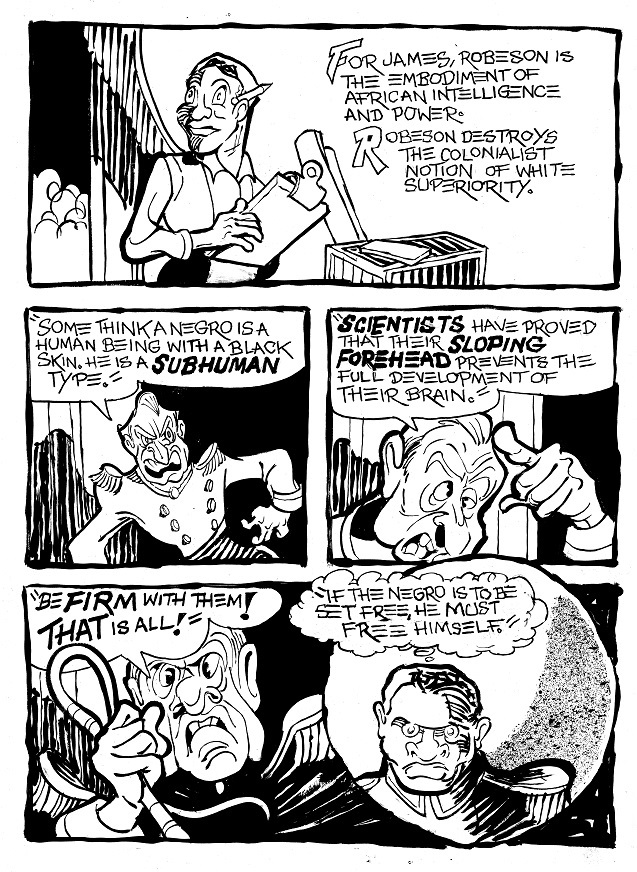

(Author’s note: This marks the first appearance of excerpts from C.L.R. James, a Graphic History, a comic art book in process, drawn by distinguished African American artist Milton Knight, edited by Paul Buhle. The excerpts – young Trinidadian James grows to self-consciousness and emigrates to London, writes a play about Toussaint Louverture, with Paul Robeson starring – are easily understood.)

(Click here to enlarge)This year marks a quarter-century since the death of Cyril Lionel Robert James (1901-89). His obituary in The New York Times, putting aside many other interests and qualities of a long and productive life, mainly described him as the last giant of Pan-Africanism. Outliving his contemporaries had surely helped, because the seemingly aged lecturer of the 1970s, the bedridden if voluble ancient of later years, personally radiated that history and regularly placed himself within it. The Black Jacobins (1938), his classic history of the overthrow of slavery in Haiti – arguably the first successful major slave revolt anywhere for a couple thousand years – would alone secure James’ place in the Pan-African pantheon. His charisma and personal contacts across continents of Africa and the Diaspora for a half-century reinforced this claim.

(Click here to enlarge)This year marks a quarter-century since the death of Cyril Lionel Robert James (1901-89). His obituary in The New York Times, putting aside many other interests and qualities of a long and productive life, mainly described him as the last giant of Pan-Africanism. Outliving his contemporaries had surely helped, because the seemingly aged lecturer of the 1970s, the bedridden if voluble ancient of later years, personally radiated that history and regularly placed himself within it. The Black Jacobins (1938), his classic history of the overthrow of slavery in Haiti – arguably the first successful major slave revolt anywhere for a couple thousand years – would alone secure James’ place in the Pan-African pantheon. His charisma and personal contacts across continents of Africa and the Diaspora for a half-century reinforced this claim.

(Click here to enlarge)There was so much more to be said, of course. Cricket fans, to the end of his life the most numerous James-readers in Britain and its former colonies, thought of him as a matchless sports commentator/historian. Anglophone Caribbean groups treated him as the would-be political architect of a never-realized Caribbean Federation, more successfully the mentor of Dr. Eric Williams, independent Trinidad’s first prime minister and one of slavery’s great historians. Or simply, if anything in James could be simple, as a heterodox Trotskyist thinker and writer, one of the most unusual and creative Marxists of the 20th century.

(Click here to enlarge)There was so much more to be said, of course. Cricket fans, to the end of his life the most numerous James-readers in Britain and its former colonies, thought of him as a matchless sports commentator/historian. Anglophone Caribbean groups treated him as the would-be political architect of a never-realized Caribbean Federation, more successfully the mentor of Dr. Eric Williams, independent Trinidad’s first prime minister and one of slavery’s great historians. Or simply, if anything in James could be simple, as a heterodox Trotskyist thinker and writer, one of the most unusual and creative Marxists of the 20th century.

And yet the books on James for more than a decade after his passing seemed firmly if not entirely fixed upon the culture critique. His literary production, his contributions to ideas about culture and how they might be deconstructed (or reconstructed) to help make sense of modern society, evidently fascinated mainly younger scholars of all colors. The depoliticization of the 1980s and 1990s may account for this conceptual tilt, as James’ political emphasis on the need for radical change and the prospects of radical change were pushed off the map. Or it was simply a part of him that had not been much rediscovered.

(Click here to enlarge)That one of the biggest C.L.R. James conferences in recent memory took place partly in a famous London cricket grounds, the Oval, reinforced the point that James-as-culture was not going away. His semi-memoir history of the sport, Beyond a Boundary (1963), is rightly seen and has been repeatedly explored as a document framed in race, despite the book’s firm grounding in the British county cricket of its own classic period highlighting W.G. Grace, the Babe Ruth of the 1880s and 1890s.

(Click here to enlarge)That one of the biggest C.L.R. James conferences in recent memory took place partly in a famous London cricket grounds, the Oval, reinforced the point that James-as-culture was not going away. His semi-memoir history of the sport, Beyond a Boundary (1963), is rightly seen and has been repeatedly explored as a document framed in race, despite the book’s firm grounding in the British county cricket of its own classic period highlighting W.G. Grace, the Babe Ruth of the 1880s and 1890s.

C.L.R. James in Imperial Britain takes us elsewhere, with high drama and great insight, into the 1930s organizer, orator and intellectual inspiration of a colonial liberation to come. A young English scholar has done the prodigious close study of assorted sources necessary to tease out the events leading up to James’ engagement with the Pan-African causes carried on in the very home of empire. The author brilliantly captures James’ frame of mind as he personally evolved in fast time to the tasks at hand. Hogsbjerg edited and introduced Toussaint Louverture, James’ otherwise forgotten play, admired if not quite commercially successful, based in his history of the Haitian events, starring the young Paul Robeson. In a way, this extraordinary theatrical experiment goes to the heart of the matter.

(Click here to enlarge)Landing in Plymouth in 1932 with a manuscript of a novel (Minty Alley, published in 1936) written back home in Trinidad but tucked away for the moment, James ghosted a memoir of the famed black cricketer, Learie Constantine, and joined him in a Lancashire working-class town where cricket was king. Here, amidst the Depression, the class struggle raged, which proved doubly interesting for James because colonial whites of his past experience had been anything but revolutionary. Soon, his keen observation of the sport as played, but also his keen sense of the social significance reflected in cricket, found him a journalistic home in the Manchester Guardian. Practically overnight, the former colonial schoolteacher became a beloved sports journalist. Within a few years, he had grown into a touring lecturer on colonial themes, sponsored by the branches of the Independent Labour Party.

(Click here to enlarge)Landing in Plymouth in 1932 with a manuscript of a novel (Minty Alley, published in 1936) written back home in Trinidad but tucked away for the moment, James ghosted a memoir of the famed black cricketer, Learie Constantine, and joined him in a Lancashire working-class town where cricket was king. Here, amidst the Depression, the class struggle raged, which proved doubly interesting for James because colonial whites of his past experience had been anything but revolutionary. Soon, his keen observation of the sport as played, but also his keen sense of the social significance reflected in cricket, found him a journalistic home in the Manchester Guardian. Practically overnight, the former colonial schoolteacher became a beloved sports journalist. Within a few years, he had grown into a touring lecturer on colonial themes, sponsored by the branches of the Independent Labour Party.

(Click here to enlarge)His rise as sports reporter was a lucky accident, thanks to his sponsor at the Guardian, Neville Cardus, who happened to be the first cricket reporter of national stature. Cardus looked to the talented youngster for a practical reason: personal relief from over-steady work. One might even say something similar of James’ anti-colonial lecturing. Learie Constantine, a real celebrity, often came from a match exhausted, cheerfully yielding the podium to the younger man. But the real accident of fate was historical: the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935. Very small groups of Africans and Afro-Caribbeans, living in Britain, acquired an oversize presence because they spoke out against imperialist injustice and in doing so, also against the whole attitude of whites (including socialistic Fabians) toward the empire’s people of color. Even benevolent British liberals believed in the need for a long stewardship ahead, continuing Mother England’s presumed preparation of backward peoples for self-government, somewhere in future generations. Black intellectuals and activists, with James among the most articulate, argued the reverse: Every colonial workers’ strike (and there were many in the 1930s), every movement in the colonies toward self-expression, demonstrated to James that these peoples were ready and eager to seize their own destiny.

(Click here to enlarge)His rise as sports reporter was a lucky accident, thanks to his sponsor at the Guardian, Neville Cardus, who happened to be the first cricket reporter of national stature. Cardus looked to the talented youngster for a practical reason: personal relief from over-steady work. One might even say something similar of James’ anti-colonial lecturing. Learie Constantine, a real celebrity, often came from a match exhausted, cheerfully yielding the podium to the younger man. But the real accident of fate was historical: the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935. Very small groups of Africans and Afro-Caribbeans, living in Britain, acquired an oversize presence because they spoke out against imperialist injustice and in doing so, also against the whole attitude of whites (including socialistic Fabians) toward the empire’s people of color. Even benevolent British liberals believed in the need for a long stewardship ahead, continuing Mother England’s presumed preparation of backward peoples for self-government, somewhere in future generations. Black intellectuals and activists, with James among the most articulate, argued the reverse: Every colonial workers’ strike (and there were many in the 1930s), every movement in the colonies toward self-expression, demonstrated to James that these peoples were ready and eager to seize their own destiny.

(Click here to enlarge)Hogsbjerg’s accomplishment is to see James in this way, lecturing from Ireland to Scotland, South Wales, Lancashire, London and the South of England, telling sympathetic, socialist working-class crowds things they had not known, had not even imagined earlier. James, the former schoolteacher and son of a schoolteacher, excelled as a lecturer not only because he was strikingly handsome, with a fine voice, but because he had been rooted in literally classic education, the education of the Classics, and a use of oratory that the Greeks would have welcomed. He was a stunning lecturer (and remained so when I first heard him, in 1970), keeping listeners hanging on each word, making his points one after another. Imagine how Wendell Phillips, Mark Twain or W.E.B. DuBois lecturing on civilization, democracy, race and colonialism must have kept their audiences alive with excitement, and we get a feeling for James at the podium.

(Click here to enlarge)Hogsbjerg’s accomplishment is to see James in this way, lecturing from Ireland to Scotland, South Wales, Lancashire, London and the South of England, telling sympathetic, socialist working-class crowds things they had not known, had not even imagined earlier. James, the former schoolteacher and son of a schoolteacher, excelled as a lecturer not only because he was strikingly handsome, with a fine voice, but because he had been rooted in literally classic education, the education of the Classics, and a use of oratory that the Greeks would have welcomed. He was a stunning lecturer (and remained so when I first heard him, in 1970), keeping listeners hanging on each word, making his points one after another. Imagine how Wendell Phillips, Mark Twain or W.E.B. DuBois lecturing on civilization, democracy, race and colonialism must have kept their audiences alive with excitement, and we get a feeling for James at the podium.

(Interviewing old-timers from a later era, after James abandoned Britain for the US in 1938, I got a slightly different impression: a good half-hour before any James lecture, the first few rows were filled with young women: he was really handsome, in what might be called the Harry Belafonte way.)

The world was changing rapidly, and if Europeans mainly looked with dread at the advancement of fascism – not to mention Stalin’s purges – the stirrings in the outlands gave James a glimpse of the future. People of color were coming onto the world stage, no matter how severe the repression, no matter how many leaders were going to be arrested and no matter how rebellious impulses would be described in respectable publications as barbaric.

Hogsbjerg explores the alternative to common disaster as James saw it looming potentially ahead: Working people in the industrialized nations would embrace the countryside rebels and vice versa. Thereby, not only fascism and Stalinism but capitalism and empire would all be swept away. The coming world war would, he hoped and believed, bring an end to systemized oppression.

Of course, no such thing happened. The global conflict that ended in the Holocaust, with the Cold War close behind, proved so exhausting to the West that the outland rebels had their chance, but it wasn’t the chance that James expected. Hogsbjerg’s account, ending in 1938, does not look ahead decades to James cursing neocolonialism and to new black leaders accepting the status, turning their revolutions into one-party states, or both of these bad choices together.

We are left, then, with a history of a brilliant beginning, in C.L.R. James in Imperial Britain, with a better conclusion yet to arrive. The idea of a past historical Third World struggle, something never taken seriously by politicians or scholars, would arrive at last in the 1960s and 1970s, firmly joined to a prospect of real Third World liberation. The continuing saga owes much to Cyril Lionel Robert James, and our knowledge of this story is vital.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.