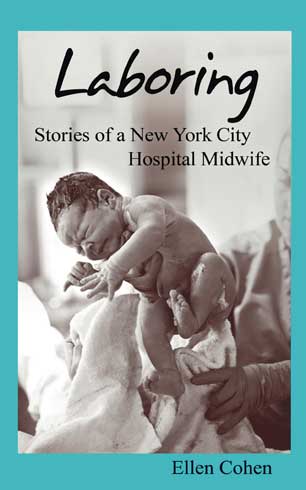

(Image: CreateSpace)Laboring: Stories of a New York City Hospital Midwife

(Image: CreateSpace)Laboring: Stories of a New York City Hospital Midwife

by Ellen Cohen, 2013, $15.95, 159 pages.

Ellen Cohen’s “Laboring: Stories of a New York City Hospital Midwife” is an insightful description of the conditions and clashes endemic to American health care and a bold celebration of human decency over worship of the bottom line.

Ellen Cohen’s dramatic memoir, Laboring, not only chronicles her three-plus decades as an urban nurse-midwife, it celebrates the blessing inherent in finding work that is simultaneously fulfilling, varied and remunerative. But Laboring is more than one woman’s nostalgic look back. It’s an insightful description of the conditions and clashes endemic to American health care and a bold celebration of human decency over worship of the bottom line.

The book opens by introducing Mia, a young woman diagnosed with schizophrenia who refused to allow doctors, midwives or aides to examine her. She had been sent to one of New York City’s public hospitals by emergency medical personnel after she was discovered, in labor, in a mid-Manhattan subway station. Cohen’s account is riveting and horrifying. “I’m not pregnant,” Mia bellowed as medical workers approached. “Get your hands away from my pussy. Pause. No, I don’t use drugs. Pause. Just my Thorazine and my crack.”

Although Mia’s story had a relatively happy ending – Cohen reports that “the baby delivered himself, cried lustily,” and was placed with a family member who also was raising Mia’s daughter – the emotional toll of the encounter weighed heavily on the labor and delivery team. Cohen is forthright in depicting its impact. And while her own relief at helping Mia deliver a healthy child is palpably presented, Cohen confesses that after the baby’s birth she sought a few moments of solace in the hospital’s female locker room. There, she let down her guard and allowed herself a good, long cry.

“I wept for the tragedy of Mia and her baby, for all the Mia’s and all their children,” she begins. “I cried for the life experience that had prepared me for precisely this moment: my own son had been diagnosed with schizophrenia ten years earlier and was lost in the dark pit of that disease. … Mia’s irrational behavior did not frighten or unnerve me. I felt no need to insist on the reality that she was pregnant if her perception was that she had a stomach ache.”

It was a lesson decades in the making, teaching Cohen to trust the patient to explain what she thought was wrong so that, as a midwifery professional, she could then treat that patient’s presenting problem. At its core is something that general patient populations rarely see in their interactions with medical workers: compassion.

For the most part, Cohen writes that it was a quality that the nurses and nurse-midwives she worked with – in public and private hospital settings and in community-based clinics serving low-income women – had in spades. Even more impressive, despite budget shortfalls and chronic understaffing, she paints a picture of deep workplace camaraderie. Even when she worked at Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx – in what was then the poorest Congressional district in the US – staff members helped one another and gave the women in their care the respect they deserved. Yes, Cohen acknowledges that it was bustling and often chaotic, with constantly changing protocols and quickly improvised treatment plans, but she clearly loved being part of the mix. And her enthusiasm is what makes Laboring such an engaging and reflective work.

Still, the workplaces she describes were far from perfect, and Cohen is careful not to idealize them. She notes, for example, the presence of doctors and administrators who were racist and sexist. She further decries illogical bureaucratic processes and cumbersome paperwork. Nonetheless, the good always outweighs the bad in this vivid account. As Cohen zooms in on the day-to-day work of serving the gynecological needs of poor and working-class women – providing contraception, performing abortions, disseminating information about the transmission of sexually transmitted infections and delivering their sons and daughters – one can almost feel the adrenalin rush of the work. It’s messy: there’s blood and there’s shit, the stuff of birth and afterbirth, but Cohen’s intense passion for her job is inspiring.

It is also, at times, heartbreaking. There are stillbirths and maternal deaths, some of them anticipated but many of them not. Cohen introduces Tonia, thrilled to be having a girl and eager to do everything right. In her mid-20s, Tonia was a nonsmoker of normal weight. She kept her appointments at the clinic and complied with all requests. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, she developed a pregnancy complication called pre-eclampsia. Labor began 12 weeks early, and the baby did not make it. “I’d done this before, too many times,” Cohen writes. “I knew the right kinds of things to say. I knew the hurtful clichés to avoid. I had attended workshops on perinatal bereavement. I had even gotten good enough at doing it that I wondered if it meant there was something wrong, very wrong, with me. I did not want to be here with Tonia. I became a midwife because I love the womanly power of birth, not to care for the sick and dying. I wanted to do what normal people do – run away from death and sadness.”

Later, as part of a team serving HIV-positive women in the early years of the pandemic, Cohen experienced the anguish of not knowing what might happen to either parent or child. Even after a seemingly healthy baby was delivered, Cohen reports the onslaught of emotions that took hold of each new mother. Their response, she writes, was always the same: “Do I dare love this baby who may die and break my heart? Then its flip side: When am I going to die and leave my baby a motherless child?”

It’s heavy stuff, and Cohen describes the emotional ups and downs in graphic terms. Still, it’s her commitment that shines through. At the same time, every so often, small kernels of personal information slip into the narrative – about her son’s mental illness, about her relationship with her spouse, about becoming a grandmother to her daughter’s child. It’s a lovely tapestry.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $50,000 in the next 10 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.