It’s time to end the era of Big Finance capitalism and an economy based on the extraction of resources, especially for energy. This statement is not an ideological proposal, but a practical one. We simply cannot continue on the present path, and as systems fail and resources become scarce, we will be forced to change what we do.

While this sounds pessimistic, it is actually an opportunity to be optimistic. Out of crisis spring new opportunities. The transition to a new economy based on sustainability and democracy has been growing worldwide for decades now and is taking root in the United States. And the new economy is being founded in principles that strengthen people, communities and the planet.

We are literally in the midst of reshaping the world and as a result, this is the time to make the new economy in a way that is redefining, as economist Joel Magnuson writes, “what is good, beautiful, fair, or wholesome, and making sure that our economic system allows us to live according to these beliefs.”

Magnuson is author of The Approaching Great Transformation: Toward a Livable Post- Carbon Economy. As the title implies, Magnuson focuses on the decline of fossil fuels and the ways this will force us to develop smaller localized economies that do not emphasize growth.

Magnuson’s work is complemented by economist Gar Alperovitz, author of America Beyond Capitalism and his newest book, What Then Must We Do?: Straight Talk About the Next American Revolution. Alperovitz writes about other crisis opportunities, like the health care and banking crises, that are forcing change. He sees the United States at the beginnings of re-making the economy so that wealth, and the political power that goes with it, is shared by all.

Both authors provide current examples of how communities and other institutions are responding to the reality of finding alternative ways to meet our needs. We can build on the experience of these models to prepare ourselves to face the environmental and economic crises and transform our social systems to be more just and sustainable at the same time.

There Is No Such Thing as Green Capitalism; Re-Localization Is Necessary

As Buckminster Fuller says, “To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.” There is a simple truth: that every system does what it is designed to do. If a different outcome is desired, then the system must be changed. This is true with the current economic system, which is rooted in capitalism and which has been expanded globally through neoliberal economic policies.

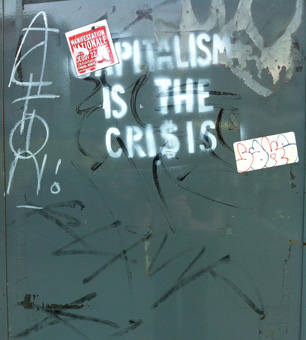

Hundreds of years of experience with the capitalist economy and the recent decades of explosive globalization have provided sufficient information to see that they are incompatible with sustainability. The main drivers of capitalism are consistent growth and increasing profits, which have been gained by exploitation of people and the planet. And globalization is possible because of cheap fossil fuels. In contrast, a sustainable economy will have to be driven by remaining within the limits of the planet’s capacity. We can’t have it both ways; we can’t have both unlimited growth and sustainability.

Magnuson argues that there is no such thing as green capitalism and that the much praised “triple bottom line” in business will only slow our demise rather than prevent it. If we are to transition to the new economy successfully, then we have to change our way of doing business and our way of life.

Many of the concepts that are being put forth to mitigate our crises are perhaps palatable, but are not real answers. Market solutions such as true-cost pricing and carbon trading have been promoted to solve our climate and energy crises because these are easy and acceptable to most people. They mean we don’t really have to change the way we live. But they won’t work, as Magnuson outlines very clearly in his book. If we pursue them, we will learn this lesson the hard way when we run out of fossil fuel completely or make the ecosystem incompatible with human life.

Likewise, simply creating systems that recycle materials, while important, is also insufficient because the vast majority of our economy is based on, as Magnuson writes, “cheap, one-time fossil fuels” and, “It would be a wild stretch of imagination to think that we could substitute this magnitude of production and consumption with recycled materials.”

There is also a dilemma regarding increasing efficiency if it is not achieved within a new economic system. Too often, increased efficiency has led to increased use and no fundamental change at the bottom line. As an example, Magnuson notes that, “Since 1980 the fuel efficiency of cars in the US has increased by 30 percent, but fuel consumption per vehicle has stayed about the same.” When something becomes more efficient, people may simply use it more.

Technology alone is also not the answer, though it is part of the solution. So far, technology has been used to increase efficiency, but the data show that “the rate with which we burn through materials has increased despite the wonders of technology.” Instead of a technological solution, we must first change the foundation of the economic system to that of sustainability, and then design technology that serves the ends we desire, not vice versa.

We are witnessing the reality of the destructive effect of “natural selection” under capitalism. Magnuson writes, “The fittest have never been those that are most efficient, but rather those that are most powerful. Also, capitalism as a system has never been about mere survival. It is about growth, accumulation, and expansion.” In nature, growth as an end goal is pathological – as we see in cancer cells or invasive plants.

The increased economic and environmental costs of fossil fuel and extractable resources will force us to create smaller-scale and more localized communities. Fortunately, this is underway around the world in the more than decade-old Transition Town Movement, which Magnuson describes in detail. Based on the ideas of permaculture, transition towns are places where the community comes together to design an “energy descent action plan” with specific steps to be taken based on the resources at hand in that particular community and its needs.

There is not one way to do things in the transition town movement. Rather, in what is called “The Great Unleashing” in transition towns, groups that are working on a variety of projects, such as renewable energy or local food production, local economies, construction, arts and more, join together to meet the needs of their community in a democratic and even joyful way.

Combining the idea of transition towns with the concepts developed by meta-economists such as E. F. Schumacher can lead to the development of new systems that replace the old systems and that are not only sustainable but actually create a better quality of life. Re-localization of the economy is an opportunity to redefine what we value and build systems that support those values.

If Not Capitalism, Then What?

Alperovitz sees examples throughout the country of the beginning of a transformation to a new democratic economy that is different from corporate capitalism and state socialism. In the new economy, wealth is shared more equitably, workers own and manage the companies they work for, Wall Street finance is replaced by public banks, and an insurance-based sick-care system is replaced by a national public health program, among many other changes. Control over the economy comes from the bottom, rather than the top.

We are in the midst of revolutionary economic change, a process that Alperovitz calls “evolutionary reconstruction.” This involves the gradual process of remaking the economy by creating new democratic economic institutions and recreating existing structures that will grow and replace the current system.

This transformation is happening because the existing system is not working for most Americans. In a country where the wealthiest 100 people have wealth equal to 180 million people, the wealth divide has become so extreme that the economy is dysfunctional. And unfettered investment-gambling by large financial institutions in derivatives worth trillions of dollars places the US and world economies at risk of another collapse.

Fortunately, we are further along the path to transformation than most of the public realizes and further along than the corporate mass media reports. Alperovitz points out: “130 million Americans – 40 percent of the population – are members of one or another form of cooperative, a traditional collective ownership form that now includes large numbers of credit unions, agricultural co-ops dating back to the 1930s, electrical co-ops prevalent in many rural areas, insurance co-ops, food co-ops, retail co-ops (such as the outdoor recreational company REI and the hardware purchasing cooperative ACE), health-care co-ops, artist co-ops and many, many more.”

What are some of the ingredients of the new economy? Alperovitz calls it a “pluralist commonwealth.” It includes cooperatives, worker-owned companies, neighborhood corporations, small- and medium-sized independent firms, municipal enterprises, state health efforts, new ways of banking and investing, regional energy, benefit corporations, land trusts and national public firms, and related democratic planning capacities like participatory budgeting.

He notes that the zeitgeist of the times is pushing a great economic debate upon us. He highlights that the Merriam-Webster dictionary announced a few months ago that the two most looked-up words in 2012 were “socialism” and “capitalism.” In addition, a Pew poll found that people age 18 to 29 have a more favorable reaction to the term “socialism” than to “capitalism” by a ratio of 49 to 43 percent. This demonstrates that Americans are looking for new answers. There is an opening for a real and serious discussion about alternatives to the present system.

Alperovitz recognizes there is no full alternative in place at this time and that worker-owned cooperatives can fall under many of the same market pressures that capitalist-owned businesses suffer. More development is needed to create improved models. One example Alperovitz points to is the Evergreen Cooperative model which links worker-ownership with community interest. He calls this “a ‘mixed’ model … that involves worker co-ops that are linked together and subordinated to a community-wide, nonprofit structure.”

For larger models to learn from, Alperovitz looks abroad to the Mondragon cooperatives in Spain and the Emilia Romagna network of cooperatives in Italy. “Mondragon has demonstrated how an integrated system of more than 100 cooperatives can function effectively (and in areas of high technical requirement) – and at the same time maintain an extremely egalitarian and participatory culture of institution control. The Italian cooperatives have demonstrated important ways to achieve ‘networked’ production among large numbers of small units – and further, to use the regional government in support of the overall effort.”

Alperovitz urges us to get serious about this discussion and “engage in a far-reaching and thoughtful debate about how a new model might be created that is both systemically sophisticated and also appropriate to American culture and traditions – a model that nurtures democracy and a culture of inclusiveness and ecological sanity.”

And while we are figuring out this new comprehensive model, we can continue to experiment with new democratic models in the workplace and the economy at local and state levels. As we discover systems that function to empower people through more equitable sharing of wealth and greater control over their economic lives, these systems will be adopted in other places. This creates momentum that propels the new system forward. In What Then Must We Do? Alperovitz calls this “checkerboarding.”

Alperovitz acknowledges the dysfunction of the political system in Washington DC, but he points out that Congress is not the only place where reform is possible. In fact, throughout history the steady progression of city-by-city and state-by-state policy changes has led to change at the national level. When neighboring states adopt a new policy that works, then nearby states will see it and copy it. He points to how this is currently occurring with gay rights and the reform of marijuana laws.

Banking and Health Care: Opportunities for Major Change

At the national level, Alperovitz sees two major “hot spots” that could cause significant structural changes with big impacts on the economy. These are health care and banking. Both are major foundations of the big-finance economy. They have in common that both are failing tens of millions of people and that there are already state and local efforts to change them.

US health care, which makes up 18 percent of the economy, is responsible for 100,000 preventable deaths each year. The number of uninsured has hovered around 46 to 50 million for years, and the number of people with insurance who are unable to afford health services is climbing.

The implementation of the Affordable Care Act (a k a Obamacare) does not address the fundamental problems of private health insurance, for-profit hospitals and the pharmaceutical industry’s profiteering. It is like putting a very expensive Band-Aid on a fatal disease. The Congressional Budget Office now estimates that when Obamacare is fully implemented, 31 million people will still not have insurance. And those who do have insurance will be paying higher premiums for less coverage. The nation will become a nation of underinsured who, when they get seriously ill, are at an even greater risk of bankruptcy.

Alperovitz notes that efforts to create single-payer health care systems are being pursued in nearly two dozen states. One state, Vermont, has come the closest to success by passing a health law that creates a path to a single-payer health system that would provide health care to everyone in the state. Even its incomplete success is already infectious: people in other states are organizing along a route similar to Vermont’s, using the concept of health care as a human right to back their demand for a single-payer system. Economic pressure will encourage state legislators to appreciate the budget savings of a single-payer health system.

Big bank finance is also an area that is dysfunctional. The banks are too big to regulate, too big to allow to fail and too big to prosecute. They were bailed out with trillions of dollars from the Federal Reserve and Department of Treasury and continue to receive $85 billion each month from the Federal Reserve in virtually free loans. Yet small businesses are starved for cash and struggle to find banks that will extend credit to them, so the economy continues to falter. It has also come to light that the model used recently in Cyprus, of taking the savings of depositors during a financial crisis, is also the model of the big banks in the United States. Rather than a bailout, the banks are planning for a bail-in if their risky investments falter – that is, they are planning on turning savings into bank stock to bail themselves out.

As a result of these factors, there is growing interest in public banks, with 20 states considering some form of legislation around the issue and some cities seriously looking at the option of a city bank. The rationale for this type of bank is hard to challenge – keep your government money in your city or state instead of giving it to Wall Street banks and use that money to leverage more funds for investment in your state. This essentially allows banks to operate in the public interest, investing in Main Street rather than Wall Street, for example through low-cost student loans, loans to entrepreneurs, responsible mortgages, greening the economy and rebuilding infrastructure.

As a historian, Alperovitz knows the future is not predictable, but he sees models being developed, the desire for something new and the dysfunction of government and the economy creating a situation such that we could be on the verge of “the next American explosion.” He sees the changes being put in place as “lay[ing] the foundation for something that could well become very important.”

Don’t Save Capitalism, Change the System

In the early 1900s, the capitalist economy was in a crisis. Decades of corruption and cronyism created conditions similar to today: mistreatment of workers, high unemployment and pollution of the environment were rampant problems. In response, a strong movement arose, made up of labor and the left, pushing for greater equality and rights. This frightened Big Finance and forced it to act. The response was New Deal policies that provided jobs and a safety net.

Many view the New Deal not necessarily as a massive social program but as an effective tool to rescue capitalism. Labor and the left were pushing for socialization of the economy. The New Deal created just enough socialization through public jobs programs and Social Security and enough relief of popular suffering that people were placated. Of course, this is a simplified version of the story. There was still strong pushback by Big Finance to limit progressive policies, which led to ups and downs throughout the 1930s, and of course World War II created an economic boom.

The point is that instead of a real transformation of the economy in the 1930s and 40s, we saw changes within the finance capitalist system to make it more palatable to the people. The overall system did not change, and over time is reverting back to the position of gross corruption and inequality, as well as the destruction of unions and the safety net that we see today.

This presents another opportunity. There will be forces from the top that will try to rescue capitalism again. One current example is the new “B Team” announced by Arianna Huffington of The Huffington Post and run by wealthy financiers Sir Richard Branson of the Virgin Group and Jochen Zeitz, who rescued Puma from financial collapse. Their goal is to “prioritize people and planet alongside profit.”

The B Team uses language that is similar to what groups who are calling for progressive change use, such as “People and the planet before profit” and “Human needs, not corporate greed.” But the B Team mission is to serve people, the planet and profit. To us, this sounds like another New Deal approach to throw fundamental change off track. We appreciate that these business leaders see the inequity, ecological destruction and unfairness of the present system and want to do something about it, but we believe the real solution is greater systemic change.

And so this is the challenge of the people. We can sit back and let Big Finance run the world economy based on profit as an important value, or we can get active and join with those creating a new economy that is democratic, grassroots and rooted in the values that are important to greater humanity. It is up to us to create the economy that serves the needs of people, protects the planet and exploits neither people nor the Earth.

Capitalism is once again at a crossroads. We can determine the path. We can create a system that is neither corporate capitalism nor state socialism but that is defined by the limits of resources and by the desires of the people. This new system will have some features of both capitalism and socialism, but will be rooted in participatory democracy, fair sharing of economic wealth and ownership, and values such as cooperation and sustainability.

The future is in our hands. A lot is already happening. Let’s dig in, work together and create not just a new world, but a better place for all of us.

To get involved in the movement to transform the economy and politics. Visit PopularResistance.org.

Further Reading:

History Teaches That We Have the Power to Transform the Nation

You can hear “How We Create the New Economy” with Gar Alperovitz on Clearing the FOG here.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.