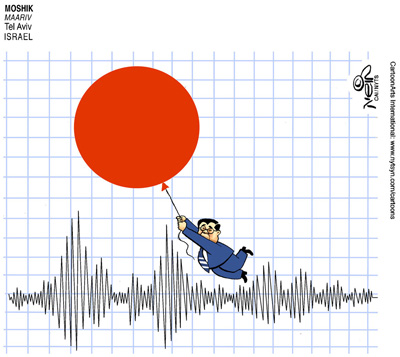

To almost everyone’s surprise, Japan – Japan! – has emerged as the advanced country most willing to break with austerian orthodoxy and try a combination of aggressive monetary and fiscal stimulus. The verdict on Abenomics is, of course, still out, although early indications are good. But how did this happen?

The Financial Times columnist David Pilling recently suggested that the change was caused by the double shock of the tsunami in 2011 and China’s overtaking of Japan as the No. 2 economy. These shocks, Mr. Pilling argues, broke through the fatalism and convinced the Japanese elite that something must be done.

Longtime readers know that I once joked that what we in the United States needed to jolt us into action on stimulus was a threat from space aliens; if the aliens were later revealed to be a hoax, no matter.

Well, it looks as if Japan has found the moral equivalent of space aliens. Good for them.

Land of the Rising Sums

The good news keeps rolling in; of course, it’s not over until the sumo wrestler sings, but there has clearly been a major change in Japanese psychology and expectations, which is what it’s all about.

Why does this seem to be working as well as it is? Long ago I argued that to gain traction in a liquidity trap, the central bank needed to credibly promise to be irresponsible — that is, to convince investors that it would not rein in monetary expansion once the economy was at full employment and inflation was starting to rise. And this is a hard thing to do.

No matter what central bankers may say, history shows that they often revert to type at the first opportunity. The examples of successful changes in expectations

tend to involve drastic regime changes, like President Franklin D. Roosevelt taking the United States off the gold standard.

And this is where the tsunami-China moral equivalent of my space aliens theory comes in: arguably, the shocks of the past two years have changed Japanese perceptions of what must be done enough to make irresponsibility — or, actually, a serious, sustained commitment to higher inflation — credible, at long last.

Meanwhile, Martin Feldstein, the former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Ronald Reagan, is demanding an end to the U.S. Federal Reserve’s efforts to do the same thing, inducing much ire from the economist David Glasner, who, in a recent post online, accused Mr. Feldstein of failing to grasp the point that it is all about changing inflation expectations. But it’s actually much worse than Mr. Glasner says.

Here’s Mr. Feldstein, in an op-ed for The Wall Street Journal on May 9, “The Federal Reserve’s Policy Dead End”: “Mr. Bernanke has emphasized that the use of unconventional monetary policy requires a cost-benefit analysis that compares the gains that quantitative easing can achieve with the risks of asset-price bubbles, future inflation, and the other potential effects of a rapidly growing Fed balance sheet.”

So, we must stop quantitative easing because it might lead to higher inflation — when expectations of (somewhat) higher inflation are precisely the main point of unconventional monetary policy.

You might even say that if quantitative easing fails, it will because people like Mr. Feldstein are doing their best to block the main channel through which it might work.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.