Poland is not yet lost. But its leaders remain determined to give disaster a chance.

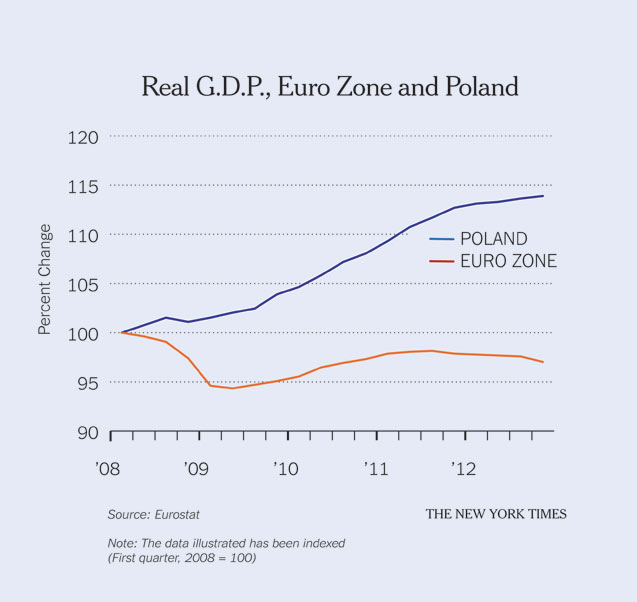

Poland is one of Europe’s relative success stories. It avoided the severe slump that afflicted much of the European periphery, then had a fairly strong recovery.

As you can see on the chart, growth has faltered more recently, largely due to fiscal austerity plus Polish officials’ puzzling decision to emulate the European Central Bank and raise interest rates in 2011.

Still, by European standards there’s a refreshing absence of sheer economic horror.

And a lot of that relative success clearly had to do with the fact that Poland not only kept its own currency, but allowed the zloty to float. As a result, during the years of big capital flows to the European periphery, Poland saw a currency appreciation rather than differential inflation, and it was able to correct that real exchange rate quickly when crisis struck.

So what does Poland’s leadership want to do? Why, join the euro, of course. It really does make me want to bang my head against a wall.

Think of Spain, Ireland, and now Cyprus. How much more evidence do we need that the euro is a trap, which can all too easily leave countries with no good options in the face of crisis? Even if you’ve bought into the legend of Latvia, which you shouldn’t, you should be willing to acknowledge that euro membership is at best a gamble, with a potentially terrible downside.

One Size Fits None

This week Joe Weisenthal at Business Insider reported on Europe’s truly dismal purchasing managers’ indexes (survey-based indexes that act as early-warning indicators for official economic data). There’s no doubt at all that the Continent is falling deeper into recession, even in the core countries.

And reading this news reminds me of something I’ve been meaning to write — namely that discussions of Europe’s troubles and the debate over austerity, often suffer from a tendency to blur two somewhat different issues.

One issue — which is the one that gets the most attention — involves the degree of austerity imposed on debtor countries. Clearly, debtor nations have very little choice about going along with demands from the troika (the E.C.B., the European Commission and the International Monetary Fund) unless they’re willing to abandon the euro — and that’s a line nobody has yet been willing to cross, although Cyprus and the onset of capital controls there bring the possibility closer.

I would argue that enlightened self-interest on the troika’s part would call for milder austerity. But even austerity skeptics would agree that some austerity in these countries is unavoidable; that’s the price of one-size-fits-all monetary policy.

But there’s a separate issue — the status of Europe as a whole.

What has happened in Europe is that the peripheral countries have been forced into extreme austerity, but this has not been offset in the core countries — in fact, core countries have also engaged in austerity measures, albeit not as severe. So the overall result has been a sharp fiscal contraction in Europe — the cyclically adjusted balance is now much tighter than it was before the crisis, even though private-sector demand remains very weak — with no offset from looser monetary policy.

European policy makers seem surprised that this policy mix has led to a double-dip recession, but they have no right to be — it’s exactly what basic macroeconomics would have told you to expect.

And this in turn tells you that the euro is an even more flawed construction than optimum currency area theory might have predicted. The theory emphasized the problem of a one-size-fits-all system in the face of “asymmetric shocks” — countries are supposed to cope separately if they’re slumping while the rest of the currency area is booming.

But it turns out that in times of broad economic weakness this problem is compounded by the asymmetry of the pressures countries face, in which troubled economies are compelled to tighten policy but less troubled economies feel no need to loosen, so that the overall stance of political and economic policy has a strong deflationary bias.

As Matt O’Brien, an associate editor at The Atlantic, recently wrote, this is the same issue countries confronted under the gold standard — a problem they dealt with, eventually, by going off gold.

If European policy makers really want to save the euro, what they should be doing is pushing hard against their system’s deflationary bias. Unfortunately, as far as I can tell they aren’t even willing to acknowledge that the problem exists.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.