Truthout contributor Richard Lichtman was away at summer camp when the United States dropped the bomb on Hiroshima. His poem exploring his memories from that day brings the enormous violence of August 6, 1945, to a revealing focal point: the thoughts and emotions of a 14-year-old boy trying to make sense of the celebration and grief unfolding around him.

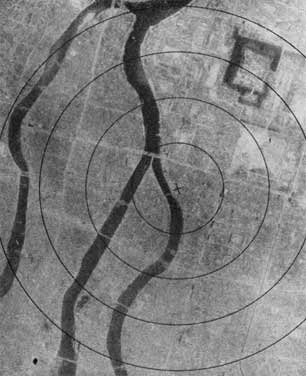

Hiroshima before bombing. Area around ground zero. 1,000 foot circles. (Photo: ibiblio.org)I believe it was a Tuesday, that day in August;

Hiroshima before bombing. Area around ground zero. 1,000 foot circles. (Photo: ibiblio.org)I believe it was a Tuesday, that day in August;

In summer camp all days tend to run together

Except for Saturday night, when there were movies,

Or Friday night and Saturday morning

When there were religious services:

Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God

The Lord is one.

You shall love the Lord your God

With all your soul and with all your might.

And these words that I command you today

Shall be on your heart

You shall teach them diligently to your children,

And shall talk of them when you sit in your house

And when you walk by the way,

And when you lie down

And when you rise

You shall bind them as a sign on your hand

And they shall be as frontlets between your eyes

You shall write them on the doorposts

Of your house and on your gates.

Strange how deeply these words settled themselves in me

And how readily I recall them still.

Of course, you can rightly say that at 14 one remembers

Yes, that’s true; but there is so much I do not remember of those days

Even filled as they were with repetition.

This day began like the others

Assembly around the flag, announcements, breakfast

And then we cleaned our bunks and made our beds

And ran to baseball, or basketball, or swimming,

Depending on the day.

And so it went in the afternoon.

More sports and swimming, and on it went

One day much like the rest but slightly different.

And yet this became the day I have never forgotten.

For sometime late in the afternoon the voice of

The head counselor came over the PA system.

His voice, as I remember it.

Was both somber and elated.

Today, he said, we had bombed Japan with the most powerful weapon

The world had ever seen.

It was said that almost 100,000 people died and more were surely to die

in the coming days.

The war would soon end he said

For nothing could withstand the power of this “atomic bomb,”

More destructive than any weapon ever, and we would right the wrong

That had been done us at Pearl Harbor.

A cry went up like the one I heard when Louis knocked out Schmeling

In their second fight in New York

And I was at my grandma’s and grandpa’s house in the Bronx

And everything turned to sound and my father looked so happy

Not because he liked Negroes so much,

But because Schmeling was a German and a favorite of Hitler’s

And an anti-Semite, and that was enough for my dad.

In time I was to hear something like it when Lavagetto hit the double

Off the scoreboard to break up Bill Bevins’ no hitter

And Brooklyn erupted in a single, glorious cry of ecstatic triumph

and I can still hear the voice of Red Barber, and that was wonderful

And still floats above my world from time to time and time to come.

But this was different

All my friends and everyone seemed excited and happier

than I had ever seen so large a group.

People ran about wildly and I had the strange feeling

that there was something pretended about it all.

They seemed to look to each other for instructions as to what to do, or how to appear,

or even, how to feel.

But Lennie was different

He sat on his bed with his head in his hands;

There was not a glimmer of joy on his face.

And I sat down too and looked at him.

Not only because he was so different from the others,

But because I liked him best of all the counselors at camp.

And looking back, now, I think it would be true to say I loved him.

He had a sense about him of right and wrong, of someone who knew the difference

and cared about it.

And sometimes we would talk

and he would say things I did not really understand

But which seemed very important and which made me want to be like him

And be liked by him.

The time I came back late from swimming and I was supposed to be cleaning the bunk,

And he looked at me and did not say anything, and I was sorry for what I did

And never did it again.

“Do you understand what happened out there today?” he asked,

And I repeated that we had bombed the Japs with a powerful bomb and we would win the war, now, so much sooner,

So everyone seemed to be saying.

“And what else?” he asked.

I said I did not know.

“Well, we killed a lot of Japs.” He emphasized the word for some reason,

“Yes,” “75,000; wasn’t that what Sam said?”

“But that was because they had attacked us and killed our soldiers

and started a war.”

“yes,” he said, “but do you think the people who died in their houses and schools and hospitals were the ones who attacked us?”

I did not know how to answer.

“They were all Japs weren’t they, like we were all Americans?”

He looked at me very quietly, very sadly,

And I began to feel the way I did that day when I came back late from swimming.

But I did not know why I felt that way

Because I did not do anything wrong

And yet, I felt as though I had

And I just went off to be by myself

And never brought the subject up again

Even when we bombed them again a few days later.

Hiroshima after bombing. Area around ground zero. 1,000 foot circles. (Photo: ibiblio.org)And even now, though I think I understand,

Hiroshima after bombing. Area around ground zero. 1,000 foot circles. (Photo: ibiblio.org)And even now, though I think I understand,

There is something between Lennie and me and I don’t know what it is.

But I do know that it was very important

And I would not have become what I am without that time between us.

And I love him and wish we could talk again and he could explain to me,

What happened that day we dropped the bomb on Hiroshima.

To see more articles by Richard Lichtman and other scholars, visit Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project.