Support Truthout’s work by making a tax-deductible donation: click here to contribute.

At a time when anti-austerity measures across the world punish taxpayers after national banking systems have been bailed out with hundreds of billions of taxpayers dollars, when both educated and working-class youth suffer historically high levels of unemployment, when the people of Tahrir Square continue to demonstrate peacefully for basic democratic values against corrupt officials and their military, when ever larger numbers of children around the world are born into poverty and when the inequalities of Western societies have reached their highest post-war levels, it is remarkable that a 94-year-old veteran resistance fighter should become an icon of resistance and an advocate of peaceful protest.(1)

Stéphane Hessel (b. 1917), the French diplomat, ambassador, writer, resistance fighter and human rights advocate, wrote a 32-page essay published as a polemic that recalled the values he had fought for during the Resistance as a basis for democratic protest today. The essay originally published as “Indignez-vous!” (2010) sold more the 3.5 million copies worldwide and has been translated into fifteen different languages. The Nation published the essay in English in 2011, and it now appears as “Time for Outrage!” (Charles Glass Books).(2) As a young resistance fighter, Hessel struggled against the Vichy government and the Nazis regime. He was a Buchenwald concentration camp survivor, and after the war was involved in helping to draft the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. He has since been a founding member of many human rights organizations and a staunch advocate of human rights, signing the petition “For a Treaty of a Social Europe,” and criticizing Israeli air-strikes in Lebanon. He has been a spokesman for the homeless and a critic of Israeli military attacks against the Palestinians. He has been awarded many honors including the French Order of Merit and Legion of Honor. He was awarded the UNESCO prize for promoting a culture of human rights in 2008 and various peace prizes. Foreign Policy named him as one of the top global thinkers in keeping alive the spirit of the French Resistance. Indeed, Hessel’s “Indignez-vous!” (2010), an ally of the Spanish M-15 Indignants movement(3), tells the young of today that their lives and liberties are worth fighting for.

His polemic raises general issues about anger in politics: Whether it is acceptable at all and in what forms? How should we deal with anger in civic education? Should we follow Seneca or Gandhi? How should we explain the complex link between political anger and violence? Indeed, is violence in a democracy ever justified? There are some like Fanon, Trotsky, Orwell and Malcolm X that would argue that it is. These critics see the philosophy of nonviolence as an attempt to foist bourgeois morality on the working class. They argued that anger is required for revolutionary change and that the link to violence is also acceptable, especially when it accompanies the right to self-defense. To them, the ideal of nonviolence is false because it presupposes both compassion and a sense of justice on behalf of one’s adversary, even in circumstances where the adversary has nothing to lose. These thinkers believe not only that political anger has a positive role to play, but that the link to political violence is not only acceptable but required, and that militant activism is strategically superior to nonviolence.

Read more: The Public Intellectual Project

The value and place of political anger depends upon the theory of politics one holds and the sort of political change one expects. It also depends upon its place in a theory of emotions. I want to entertain the relationship between anger and the legitimate expression of anger, especially its expression in forms of discourse and forms of political action. I also want to explore the link between political anger and forms of political action that derive from a philosophy of nonviolence. Both of these issues are fundamental to political education. There are other issues that lie near the border of these issues, but I do not have the time to explore: what is the relationship between political anger and the state’s exercise of power against its own people and against other states and other peoples? What of war as the supreme act of violence and what is its relation to political anger?

Seneca’s famous essay “On Anger” views it as a kind of madness, rejecting all forms of spontaneous and uncontrolled forms of rage. In war, as in sport, Seneca counsels it is a mistake to become angry and he talks of mastering anger and how to deal with anger in others: avoid being too busy; do not deal with anger-provoking people; avoid unnecessary hunger or thirst; listen to soothing music; check one’s impulses; become aware of personal irritations; do not be too inquisitive of others; do not be too quick to believe that someone has slighted you; put yourself in the place of the other person.(4)

Seneca’s techniques would not be too out of place in a modern anger management course: shades of the 2003 slapstick comedy with Adam Sandler and Jack Nicholson called “Anger Management” with the subtitle “Feel the Love.” Sandler plays mild-mannered Dave Buznik, and Nicholson plays an aggressive instructor called Dr. Buddy Rydell, a psychopathic character who steals his girlfriend and nearly ruins his life. One of the taglines is “Let the healing begin.” Seneca seems to me like a modern Rydell or anger management therapist. Seneca’s techniques are the direct forerunner to a system of therapeutic techniques and exercises by which someone with excessive or uncontrollable anger can be taught ways to control or at least reduce the angry emotional state. Often, it is taught alongside assertiveness training in communication which purportedly allows for the healthy expression of the emotion.

Anger gets a bad press. By contrast, we never hear of “happiness management” or “joy training.” Seneca’s negative assessment of anger is echoed by Galen and by most religious-based moral codes: it is one of the seven deadly sins in Catholicism; it is equated with unrequited desire in Hinduism; it is defined as one of the five hindrances in Buddhism; in Judaism, anger is considered a negative trait; and in the Qur’an, anger is attributed to Muhammad’s enemies.

By comparison, Aristotle in the “Rhetoric” attributes some value to anger that has arisen from perceived injustice because it is useful for preventing injustice.(5) In chapter 2 of book I, Aristotle defines rhetoric by reference to reason, to human character and to emotions; and in chapter 3, he defines three categories of oratory including political, forensic and ceremonial. This is important because it establishes the link between political anger and forms of discourse suited to its expression.

Following Aristotle, I will argue for the positive rehabilitation of anger. Political anger, if this concept and distinction can be sustained, I would say is mostly related to a denial of freedom and/or a perceived injustice. When women were denied the vote in New Zealand before 1893 they were angry and their anger was expressed in organized protest and in different forms of political discourse and organization. The same is probably true for women who were denied the vote in France before 1948, in Switzerland before 1972, in Afghanistan before 2001 and by women living in Saudi Arabia today: the abrogation of freedom often and appropriately results in political anger that often gets expressed in legitimate forms of protest and discourse that constitute part of the struggle for rights. All of this is in accord with Hessel.

The expression of political anger in a democracy is perfectly legitimate and, indeed, even politically desirable as an antidote to the exercise of arbitrary or illegitimate power that involves the abrogation of freedom and unfair and unequal treatment before the law. Mahatma Gandhi once remarked: “I have learned through bitter experience the one supreme lesson to conserve my anger and as heat conserved is transmitted into energy, even so our anger controlled can be transmitted into a power that can move the world.” He drew on Tolstoy’s interpretation of the Gospels and was inspired by satyagraha (devotion to the truth) and ahimsa (nonviolence) as a basis for his civil resistance and disobedience that he developed in South Africa against state racism and then later in the struggle against the British Raj.

My approach is to historicize democracy and to see the legitimate expression of political anger as an engine of change aimed at the extension of existing freedoms and the generation of new freedoms. I want to emphasize the relationship between political anger and forms of discourse suited to the expression of anger that have developed a home in our language and culture.

Anger is an ancient emotion and, as Susanna Braund and Glenn W. Most (2005) demonstrate, it is found everywhere in the ancient world, from the very first word of the Iliad through all literary genres and every aspect of public and private life. Yet, it is only very recently that classicists, historians and philosophers have begun to study anger in antiquity. The current debate about anger in antiquity took place among the classicists in the 1990s – Martha Naussbaum, Douglas Cairns, David Konstan, Richard Sorabji and William Harris.

Anger and epic seem to go hand in hand. The wrath of Achilles occurs in the Iliad; the debate about anger is explored at the end of the Aeneid; Aristotle defines anger positively in the “Rhetoric.” The gods are often said to be angry and the debates about the ancients have also focused on the delegitimization of women’s anger in the Greek polis while shoring up masculine anger, providing a valorization of anger in Athenian society.

In “The Emotions of the Ancient Greeks,” David Konstan (2006) argued:

the emotions of the ancient Greeks were in some significant respects different from our own and that recognizing these differences is important to our understanding of Greek literature and culture generally…. [p. Ix]

He also argued that the Greeks’ conception of the emotions has something to tell us about our own views and, in particular, about the nature of certain emotions. In one sense, we might say that by considering the emotions and, in particular, anger in relation to modern democracy, we are engaging in a “psychopathology of democracy.”

Aristotle suggested that to know how to stir an emotion you must know what the emotion is about and to know what it is about you must know what the people engaged in the relevant transaction are thinking: “Anger may be defined as an impulse, accompanied by pain, to a conspicuous revenge for a conspicuous slight directed without justification towards what concerns oneself or towards what concerns one’s friends.” (Bk II, Chap. 2) The great strength of Aristotle’s analysis, Konstan argued, is not that he gets the emotions absolutely “right” where others get them absolutely “wrong,” but that “[his] approach … better describes what the emotions meant in the social life of the classical city state,” which provides the “narrative context” for his account. (p. 28) Yet, Aristotle advised us about anger in order to enlighten us about the force of deliberative oratory that can influence citizens in the life of the assembly that was “intensely confrontational, intensely competitive and intensely public.” Aristotle was writing for

a world in which self-esteem depends on social interaction: the moment someone’s negative opinion of your worth is actualized publicly in the form of a slight, you have lost credit and the only recourse is a compensatory act [i.e., revenge in anger] that restores your social position. (74f.)

Konstan goes on to say that “the Greeks were constantly jockeying to maintain or improve their social position” and that they “were deeply conscious of their standing in the eyes of others” and “intensely aware of relative degrees of power and their own vulnerability to insult and injury.” (p. 259) While I accept the differences in the emotional worlds of the classical Greeks and that of the modern West today, especially for women, Aristotle’s lessons and descriptions do not seem too far-fetched as descriptions of the American Congress, the classroom, the playground, political party gatherings, parliamentary debates and even philosophy of education conferences.

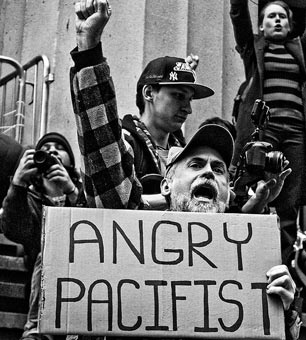

When we talk about anger in a positive sense in modern democracies, we should draw distinctions among annoyance, irritation, frustration, mild anger, outrage and fury. We might even draw the distinction between passive anger and aggressive anger that spills over from discourse and peaceful protest into violence and bullying. The discursive forms of political anger – the rant, the tirade, the diatribe, the harangue and satire that combine anger with humor, sometimes with cynicism and parody, sometimes with irony or sarcasm, often with burlesque, exaggeration and double entendre, all produce the militantly angry forms of discourse. But can anger expressed in discourse be violent?

In this context, I am reminded of the play and the 1959 black and white British film based on John Osborne’s play “Look Back in Anger,”(6) directed by Tony Richardson and starring Richard Burton and Claire Bloom, about a love triangle among Jimmy Porter, a disaffected lower middle-class, university-educated man, who lives with his wife Alison, the daughter of a retired colonel in the British Army in India, and Helena, an actress friend of Alison’s. Intellectually restless with “a chip on his shoulder,” Jimmy reads the papers, argues and taunts his friends over their middle-class acceptance of the world around them. He rages to the point of violence, reserving much of his bile for Alison’s middle-class friends and family.

Jimmy: Somebody said – what was it? – We get our cooking from Paris – that’s a laugh – our politics from Moscow and our morals from Port Said. You know, I hate to admit it, but I think I can understand how her Daddy must have felt when he came back from India, after all those years away. The old Edwardian brigade do make their brief little world look pretty tempting. All home-made cakes and croquet. Sits on cistern. ALISON wanders to table and ashtray. Always the same picture: high summer, the long days in the sun, slim volumes of verse, crisp linen, the smell of starch. If you’ve no world of your own, its rather pleasing to regret the passing of someone else’s. But I must say its pretty dreary living in the American Age – unless you’re American, of course. Perhaps all our children will be American? That’s a thought, isn’t it? [Act 1, p. 12]

“Look Back in Anger” came to exemplify a reaction to the affected drawing-room comedies of Noel Coward, Terrence Rattigan, and others, which dominated the West End stage in the early 1950s. Kenneth Tynan (1964), who referred to the play’s “instinctive leftishness” in his Observer review, wrote in a piece on “The Angry Young Movement” commenting that Jimmy Porter “represented the dismay of many young Britons … who came of age under a Socialist government, yet found, when they went out into the world, that the class system was still mysteriously intact.”

Osborne, who died in 1994, was notorious for the “theatre of anger” directed against the British establishment. Olivier was dismissive of the play and thought it bad theater. Yet, the play transformed British theater, and Porter captured the angry and rebellious nature of the post-war generation, spawning what George Fearon, a press officer, referred to as “angry young men,” a group of playwrights including Osborne and Kingsley Amis who were characterized as being disillusioned with traditional English society.

Not surprisingly, their views, not to be seen as a movement, were usually from the left (though Osborne increasingly moved to the radical right), sometimes anarchistic and concerned with describing various forms of social alienation in postwar Britain. The group was nurtured by the Royal Shakespeare Company with overlaps with the Oxbridge malcontents (Kingsley, Philip Larkin, John Wain) and with a small group of young existentialist philosophers including Colin Wilson, Stuart Holroyd and Bill Hopkins. Sometimes the “angries,” as they were referred to, were seen also to include Harold Pinter, John Braine, Arnold Weskler and Alan Silitoe. This was a formidable force in British theatre, even if the literary high ground had been stolen by James Joyce and Dylan Thomas.

It was a movement that had only one thing in common – the class positionality of a kind of political anger aimed against the Establishment that explored existentially the alienation of human beings, celebrated working-class heroes and led to the rediscovery and legitimacy of working-class culture. Colin Wilson claimed they were the first group of working-class writers. In his masterful literary biography of Osborne subtitled “The Many Lives of an Angry Young Man,” based on Osborne’s private notebooks, John Heilpern (2008) recorded John Mortimer’s remark, “He [Osborne] was an absolutely lovely Champaign-drinking man,” adding “and an absolute shit, of course.” Osborne’s own assessment when asked if he was a paranoid person confirmed this assessment: “Oh yes,” he replied, “I see treachery everywhere. In my opinion, you should never forgive your enemies because they are probably the only thing you’ve got.” (p. 20)

Anger and the culture of political anger occupied a central place in British life in the late 1950s and sixties and in periods thereafter. It was central to the anti-war culture in the US that overturned American foreign policy and the war in Vietnam. From that time, we look forward in anger to the late 1960s, to the ’60s counterculture that erupted in forms of organized protest by students and young people across the Western world, fuelled by the anti-war protest songs of Donovan, Dylan and Joan Baez, among others. This was also a distinctive “culture of anger” inspired by the ideal of peaceful protest that invented new cultural forms of protest and civil acts of disobedience to “ban the bomb” and demand democratic rights.

The counterculture movement rode on the back of the civil rights movement and coalesced with the free speech movement at Berkeley, with the constellation of the New Left inspired by Herbert Marcuse and others, second generation women’s rights and feminism, environmentalism and the organization for gay rights. Of my generation, who doesn’t remember the “sit-in,” the “happening,” the slogans – “make love not war” – and taking part in peaceful rallies? These forms of protest learned the new forms of democratic action including pacifist and nonviolence expressions of political anger from anti-colonial struggles.

Only by studying their own culture and, in particular, the culture of the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, will students and the youth of today understand the significance of student protests and the counterculture that invented new forms of expression of political anger in discourse, music, literature, drama, dress and style that were predominantly nonviolent, consistent with its underlying values and effective as a means of public pedagogy.

Students today suffering the neoliberal crisis after the big financial meltdown, face mounting debt with few prospects for work. They are relearning the lessons of the first postwar generation of citizen activism, critical democratic consciousness and its successes against all bureaucratic and totalitarian perversions of social democracy. Western democracies and political rights are being looked to as a model by the youth of the Arab Spring, not the story of free trade ands global capital, but indigenous narratives that borrow from the alternatives of social democracy and the tradition of nonviolence. Today more than ever, we need to convert political anger into mass mobilizations against the elimination of powers of collective bargaining and the move against teachers and students, as governments, having bailed out the bankers, now set about cutting their education budgets and laying off teachers.

The philosophy of nonviolence is an effective strategy for social change that channels political anger into acceptable forms of protest within a democracy. Nonviolent campaigns include a variety of forms of discourse and social action: critical forms of education, creative humor and persuasion, civil disobedience, nonviolent direct action and targeted communication. Nonviolence is a powerful tool with a respectable history – the suffragettes, Gandhi, Martin Luther King, César Chávez. Advocates of nonviolence believe cooperation and consent are the roots of political power; if that is so, then the peaceful expression of political anger derives from a concept of political love.

If peaceful protest fails to move the authorities, then revolutionary protest will follow; if revolutionary protest fails, revolutionary violence most surely will occur.

References:

Braund, S and Most, G. W. (2005) “Ancient Anger: Perspectives from Homer to Galen” (Yale Classical Studies XXXII). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harris, William (2002) “Restraining Rage: The Ideology of Anger Control in Classical Greece” Harvard University Press.

Konstan, David (2006) “The Emotions of the Ancient Greeks: Studies in Aristotle and Classical Literature” Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Tynan, Kenneth (1964) “Tynan on Theatre,” Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Footnotes:

1. I am indebted to Christine Henderson for alerting me to Hessel’s polemic. She is the partner of Frank Docherty, the Scottish surrealist political painter who has an anti-war and anti-state burecracy series. All his paintings are ironic or cuttingly humorous. See here.

2. Indigène editions official web site. Publisher of “Indignez-vous!” See also: “Time for Outrage!” Charles Glass Books; English translation of “Indignez-vous!”; biography and writings of Hessel; Denis Touret. (French). Finally, see, “A talk with Stephane Hessel at The American University of Paris“; “Stephane Hessel and the Handbook of the Revolution” – TIME.

3. See the official blog here, and the collection on the Spanish revolution here.

4. See Seneca’s Essays, vol. 1, with “On Anger.” See also Alain de Botton’s “Seneca on Anger – Philosophy: A Guide to Happiness.”

5. See the full text based on the translation by W. Rhys Roberts and hypertext by Lee Honeycutt here.

6. See the film version available here and the movie trailer here.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $34,000 in the next 72 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.