Washington – Congress isn’t just stuck in partisan and ideological gridlock: It’s broken.

Once again this month, and probably throughout this year, lawmakers are mired in stalemates over what used to be routine solutions to commonplace issues.

They can’t agree on freezing student loan interest rates, which are due to double July 1. They’re stymied on highways and infrastructure policy. They’re fighting over laws that protect victims of domestic violence.

And the big stuff? The automatic cuts in defense and domestic spending scheduled for next year? The tax increases scheduled to go into effect Jan. 1? Congress is ignoring those for now, despite increasingly nervous financial markets. Those are topics to be addressed after the Nov. 6 elections.

And the big stuff? The automatic cuts in defense and domestic spending scheduled for next year? The tax increases scheduled to go into effect Jan. 1? Congress is ignoring those for now, despite increasingly nervous financial markets. Those are topics to be addressed after the Nov. 6 elections.

“It all comes down to my club against your club,” said former Rep. Mickey Edwards, a Republican. “Both parties are only playing for the next election and not worried about solving problems.”

The problem, experts say, is that the needs and tactics of political parties, not the acumen and strategies of legislators, now rule the congressional process. The occasional exceptions – such as this month’s reauthorization of the Export-Import Bank by strong bipartisan majorities in both houses – are so rare that they only underscore the gridlock.

In their new book, “It’s Even Worse Than It Looks,” veteran Washington scholars Norman Ornstein of the American Enterprise Institute and Thomas Mann of the Brookings Institution argue that Republicans in particular have become so extreme that compromise is all but impossible. The American Enterprise Institute is center-right, Brookings center-left, and Mann and Ornstein are renowned as authoritative analysts from the Washington establishment.

“There is one party that has really gone off the tracks,” Mann said during a Brookings discussion of Congress, referring to the Republicans.

In their book, the authors called the GOP an “insurgent outlier – ideologically extreme; contemptuous of the inherited social and economic policy regime; scornful of compromise; unpersuaded by conventional understanding of facts, evidence and science; and dismissive of the legitimacy of its political opposition.”

Democrats, though, “are not angels,” Ornstein noted. He recalled how, while they were in charge of the House of Representatives from 1955 to 1995, they often were arrogant and routinely shut Republicans out of serious policy deliberations.

But the two parties did work together in earlier eras. The bipartisan Social Security commission in 1983 helped stabilize the system for a generation. Tax deals throughout the 1980s got support from both parties. Foreign policy long had a bipartisan hue.

Republicans, predictably, disagree with the Ornstein-Mann analysis.

GOP leaders cite the Senate vote earlier this month on freezing the student loan rate as an example of fresh Democratic arrogance. The rate for subsidized Stafford loans, now 3.4 percent, will double unless Congress acts.

House Republicans would pay for the change by cutting a public health fund that Democrats support. Democrats prefer to raise taxes on the wealthy, an idea they’ve pushed repeatedly, knowing that Republicans opposed to any tax increases will vote no.

“What matters now for Democrats is they find a way to drive a wedge between Republicans and a constituency they are looking to court ahead of the November elections,” charged Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky. President Barack Obama has been actively courting the youth vote – a key part of his re-election coalition – with his calls to stop the student-loan rate increase.

Democrats countered that it’s Republicans who are cynically playing politics with the loan issue.

“By bringing a bill to the floor that says we will do this, but we will only reduce the interest rates by making an assault on women’s health, (is) a continuation of their assault on women’s health,” said House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif

The standoff goes on.

Among the upcoming duels is a battle to renew the 18-year-old law aimed at helping victims of domestic violence. The Senate, on a largely party-line vote, approved changes in the popular law last month that more explicitly provide protection to gays, transgender victims and illegal immigrants. The House left out those changes and passed its version last week 222-205. The majority consisted of 216 Republicans and six Democrats; 23 Republicans joined 182 Democrats in opposition.

Some Republicans said singling out such groups as transgender victims was unnecessary, that the law already protected them. Sen Charles Grassley, R-Iowa, called the effort “cynical partisan game-playing that Americans are sick of.”

Subjects such as student loans, domestic violence and the still-stuck effort to rewrite the laws that govern highway and infrastructure spending used to be the kind of business that Congress methodically and easily approved year after year.

Today, almost everything on Capitol Hill is taken hostage in the partisan war. There’s no single easy explanation, but there are several.

Foremost is the improved ability of political parties, flush with campaign cash and armies of “message experts,” to shape a lawmaker’s message and make sure that friendly constituencies are informed instantly via Facebook, Twitter and other devices. Congressional districts also can be scientifically drawn, almost block by block, to assure that House members have ideologically monolithic districts.

“In most districts, the election is over with the primary,” said Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore, a 26-year veteran. “People don’t have to bother to appeal to broader constituencies.”

Primary turnouts tend to be lower than those in general elections, and those who vote in primaries are often the parties’ most extreme ideologues. Earlier this month, champions of legislative craftsmanship felt a new shudder when Indiana State Treasurer Richard Mourdock, proudly questioning the value of compromise, soundly beat six-term incumbent Sen. Richard Lugar in the state’s Senate Republican primary.

Mourdock’s attitude, Ornstein said, can’t “create a sense of legitimacy” for long-term solutions to big problems.

But most politicians see little value in selling short-term pain – tax increases or painful spending cuts –in return for longer-term gains such as lower federal debt and, presumably, a healthier economy.

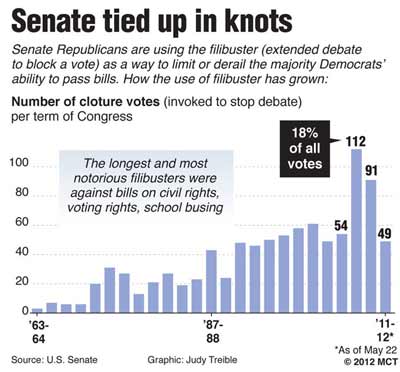

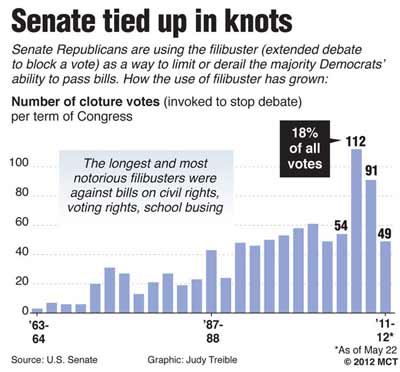

Then there’s the relentless exploitation of the Senate’s famous “filibuster” rule by both parties when they’re in the minority, to force 60-vote super-majorities to pass anything. That gives the minority party – currently Republicans – the power to block almost everything.

“There hasn’t been a price to pay for obstruction for obstruction’s sake,” Ornstein said.

Social media encourage the extremes. “We have this explosion of technology, and it changes things,’ said Sen. Richard Shelby, R-Ala., a 34-year congressional veteran.

Ideological die-hards remain unyielding.

“You have to stand on principle. There’s a difference between compromise and capitulation,” said Rep. Steve King, R-Iowa, a tea party favorite who’s in a tough re-election race. “There are certain principles I believe in, and I don’t intend to change.”

Hope for breaking these deadlocks rests with deadlines and crises. Most lawmakers expect that as the July 1 loan-rate increase deadline approaches, compromise will prevail. And domestic violence laws and highway projects have too much widespread support to let them lapse.

Fear that its inertia will trigger economic disaster also can motivate Congress. It finally agreed to a debt-limit extension last August at the last minute, after dire warnings from financial market experts of the consequences of inaction

But at the moment, there’s little motivation to talk seriously about big items such as the Bush-era tax cuts and the 2011-12 payroll tax cuts, which expire at the end of the year. Or amending the $110 billion worth of automatic spending cuts – half for defense and half for domestic programs – that are slated to take effect Jan. 2.

“If we made tough decisions, we’d have to take votes,” Sen. Jon Kyl, R-Ariz., explained sarcastically. “If we made votes, those votes would be on the record. If those votes are on the record before the election, our constituents would know what we really think and how we act, and some of them may not like it.”

Kyl isn’t seeking re-election. But those who are don’t seem optimistic that Congress can heal itself quickly.

“There are a lot of new guys in town who didn’t grow up the way I grew up,’’ said Rep. Nick Rahall, D-W.Va., who was first elected in 1976. “I believed you don’t get 100 percent of everything you want.”

© 2012 McClatchy-Tribune Information Services

Truthout has licensed this content. It may not be reproduced by any other source and is not covered by our Creative Commons license.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.