Executives in the energy exploration and drilling industry practically salivate when talk turns to possibilities in Pennsylvania.

Perhaps fittingly, their nickname for the Keystone State is “the Saudi Arabia of natural gas.”

Being heralded as twin energy founts, however, is about where the similarities between the natural gas-rich Middle Atlantic state and the oil-laden Middle Eastern nation end. Their geographies are studies in extreme contrast and size-wise, two Pennsylvanias could be shoehorned into just one Saudi Arabia.

Right now, the hydraulic fracturing fever sweeping their state has many Pennsylvanians in turmoil. In addition to concerns about impacts on their water and air, state residents are worried about the indelible footprint fracking infrastructure is in the midst of stamping on the forests, open spaces, rural hamlets, agricultural fields and public lands they call home.

After all, William Penn is the Englishman and Quaker credited with founding the state. Back in 1681 he christened the region Sylvania — the Latin word for woods — for obvious reasons.

So, just how will this hunt for buried energy treasure transform the landscape of a state that draws millions of tourists to its state parks and prides itself on its productive forests?

“This is going to be like a spider web spun across the state,” John Quigley, a former state environmental leader, told SolveClimate News in an interview. “The scale of this is just unimaginable. At this point, I don't think anybody can fathom how much.”

Quigley served as secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources from April 2009 until January when a new administration headed by Republican Gov. Tom Corbett took office. He is now an adviser to a former employer, Citizens for Pennsylvania's Future. Known as PennFuture, it's a statewide public interest organization based in Harrisburg.

“Hydraulic fracturing will dwarf the cumulative impact of all of the previous waves of resource extraction that punctuate Pennsylvania history,” Quigley said, ticking off a list of successive destructive acts that began with the clear-cutting of old growth trees across the states northern tier to fuel the Industrial Revolution, then morphed into the drilling of the first oil well in Titusville and the rise of King Coal. “It's impossible to downplay or avoid the environmental impacts.

“Not only is this going to cause massive habitat fragmentation but what emerges will be a fundamentally different Pennsylvania,” he continued. “The question is, are we going to repeat the mistakes of the past?”

Why Pennsylvania?

Geologists hail Pennsylvania as a natural gas mother lode because nearly two-thirds of the state's 28 million acres rests atop a yawning sheath of sedimentary rock formed around 400 million years ago during what scientists label the Devonian Period.

What's called the Marcellus Shale is basically a thick horizontal seam undulating anywhere from 4,000 feet to 10,000 feet beneath the Earth’s surface. It measures about 150,000 square miles and stretches from the lower tier of New York State south through parts of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Ohio, West Virginia and a sliver of Virginia.

The Appalachian Basin is reportedly packed with enough natural gas, experts estimate, to meet the nation's energy needs for nearly two decades — or perhaps longer.

The organically rich shale is already naturally pocked with fissures. Companies use a relatively new technology known as hydraulic fracturing to open up those cracks and release the trapped gas.

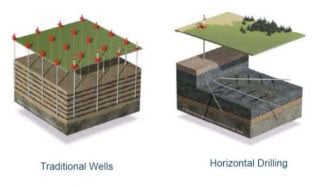

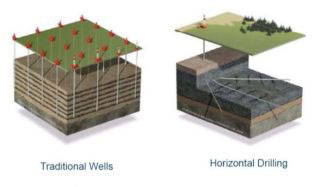

This technology, which combines traditional vertical drilling with horizontal drilling and rock fracturing appeared on the scene in Pennsylvania's Marcellus Shale close to six years ago.

In a nutshell, fracking requires companies to drill a vertical well about a mile deep. From that point, the well can “grow” a long “arm” that bores horizontally into the shale formation for close to a mile. Drillers then inject sand, millions of gallons of water and a special recipe of potentially toxic lubricants and chemical additives under extremely high pressure to further fracture the dense black shale and draw the liberated gas to the surface. Wells can be fracked numerous times.

Unparalleled Footprint

In Pennsylvania, the Marcellus Shale rests beneath the entire western half of the state and the northeastern corner. Numbers gathered by state authorities reveal that natural gas companies have thus far leased about 7 million acres of public and private property — about one-quarter of the state’s entire land mass.

That high volume prompted the Pennsylvania chapter of The Nature Conservancy to delve into what impact such an intense fracking footprint will have on the flora and fauna the nonprofit organization is dedicated to protecting.

Already, 2,000-plus wells have been drilled statewide. But state figures reveal that the number of permits issued to companies has ballooned from a mere four in 2005 to 3,314 through 2010.

By collaborating with state authorities and gas companies for its research, the conservancy figures at least 60,000 new wells will be drilled through the year 2030. That will eat up at least 90,000 acres over the next two decades, with the potential to double to 180,000 acres if the number of new wells grows at the same pace through 2050.

That might not seem egregiously enormous in a state as massive as Pennsylvania, but consider this. A footprint such as that would stomp over close to one-third of Rhode Island.

Nels Johnson, director of conservation programs for the conservancy's Pennsylvania chapter, told SolveClimate News that the northwestern segment of the state has a long tradition of shallow natural gas development.

“With the Marcellus, there might be fewer pads because of a company's ability to drill horizontally but the tradeoff is that each pad is bigger and much of this infrastructure is going into areas not previously impacted by gas development,” Johnson emphasized. “It's a new impact.”

Alarming Conservancy Arithmetic

The Nature Conservancy lays out its concerns about the effects of hydraulic fracturing in a November 2010 report titled “Pennsylvania Energy Impacts Assessment.”

“Many factors — including energy prices, economic benefits, greenhouse gas reductions and energy independence — will go into final decisions about where and how to proceed with energy development,” the report states. “Information about Pennsylvania's most important natural habitats should be an important part of the calculus about trade-offs and optimization.”

Arithmetic shows that while each drilling pad covers a relatively reasonable 3.1 acres, the footprint for each well actually rings in at 8.8 acres because of the accompanying roadways and other infrastructure — such as that for hauling and storing water — that have to be built.

Each pad can accommodate up to 10 wells; the conservancy used an average of six for the sake of its calculations. So 8.8 acres multiplied 10,000 times (60,000 total wells with six wells per pad) is where the 90,000-acre figure originated.

“When you look at how much of the Marcellus Shale covers Pennsylvania, 90,000 acres isn't a huge percentage but this is about where it happens and how it happens,” Johnson said. “A lot depends on where those 90,000 acres get cleared because this is a major conversion.”

Johnson and others pointed out that Pennsylvania's mountainous terrain is forcing gas companies to be more judicious with drilling decisions than they might be in a state such as Texas with mile after mile of flat, open terrain.

Oddly enough, even though everything about Marcellus development is big — including pad size, water use and supporting infrastructure — the ability to accommodate up to 10 vertical wells per pad actually offers a bit of solace to conservationists.

Think about this. One vertical well on a single pad can “drain” natural gas from, say, 10 to 80 acres. But a heftier pad with numerous vertical wells to accommodate far-reaching horizontal drilling technology can pull in gas from 500 to 1,000 acres.

Thus, the impact on forests, freshwater and rare species can be lessened if those pads are strategically placed instead of scattered willy-nilly without forethought.

“The lateral reach of Marcellus wells means there is more flexibility in where pads and infrastructure can be placed relative to shallow gas,” the conservancy report states. “This increased flexibility in placing Marcellus infrastructure can be used to avoid or minimize impacts to natural habitats in comparison to more densely spaced shallow gas fields.”

Conservancy in Midst of Second Study

Soon, the conservancy will be releasing a second report that piggybacks onto its initial release by examining the environmental impact of the four levels of underground pipelines that are constructed to eventually deliver natural gas to customers once it is harvested from the Marcellus Shale.

For instance, a gathering pipeline is built near each drilling pad to collect the freshly extracted gas. From there, it is shipped to what's called a midstream pipeline, an intermediary that connects it to the backbone of the system, a transcontinental pipeline that delivers natural gas long distances to major markets. These large cities have storage facilities that tie into a network of distribution pipelines that deliver the finished product to commercial, industrial and residential customers.

“Those distribution lines don't have too much impact on the environment,” Johnson noted. “The concern is with those other three levels of pipelines.”

Preliminary estimates collected by researchers at Pennsylvania State University show that new well development will require about 10,000 miles of gathering lines that measure 18 to 24 inches in diameter and require 100 feet of right-of-way. That alone would devour another 90,000 acres of land — doubling the impact of wells, roads and accompanying infrastructure by the year 2030 to 180,000 acres.

The Penn State figure doesn't include the potential footprint of midstream or transcontinental lines, Johnson said, adding that they likely won't be included in the conservancy report because those numbers are too difficult to project at this juncture.

“Clearly, the heart of some of Pennsylvania's best natural habitats lies directly in the path of future energy development,” the conservancy report warned. “Integrating … conservation priorities into energy planning, operations and policy by energy companies and government agencies sooner rather than later could dramatically reduce these impacts.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.