Part of the Series

Solutions

Solution to Deal With the Department of Energy’s Radioactive Waste Stabilization Programs: Open Them to Competition

By Greg Williams, Edited by Dina Rasor

From the White House Blog in February 2010:

“[Obama] announced loan guarantees through the Department of Energy to operate two new nuclear reactors at a plant in Burke, Georgia. It will be the first new [US] nuclear power plant in nearly three decades. The plant is expected to create approximately 3500 construction jobs and 800 permanent jobs. When the nuclear reactors come online, they will provide reliable electricity for 1.4 million people in Georgia. Under the Energy Policy Act of 2005, the plants will be held to strict standards to find ways of disposing waste safely, and avoid or reduce emissions of greenhouse gases.”

Introduction

President Obama intends to use nuclear energy for future US use. One of the persistent problems with using nuclear is what to do with the waste and, for decades, the federal government has not made much progress in dealing with nuclear waste.

The US Department of Energy (DOE) has been trying to stabilize roughly 90 million gallons of radioactive waste produced by our current and past nuclear weapons programs(i). Twenty years ago as a recent college graduate, I studied this effort and was surprised to find how little the US takes advantage of our allies’ achievements in this area. Now, revisiting that study, I’m dismayed to find that we are now actually further from our stabilization goals than we were 20 years ago(ii) , and we still seem to be ignoring the help our allies seem to offer. The leader of these allies – France – has greater overall capacity than we do,(iii) and several other countries currently accept overseas waste for processing.

From the outset, DOE has acknowledged our allies achievements in this field, but has steadfastly maintained that they know better how to handle US waste. Twenty years ago there was already enough evidence to raise suspicion that DOE’s perspective was compromised by a “not invented here” mentality. After two decades of negative progress, I propose that it is time to subject DOE and its contractors to more pressure in the form of competition from British and/or French facilities. Specifically, I propose that DOE make 1 percent of the outstanding budget for DOE high-level radioactive waste disposal available to study the feasibility of using other, well-established stabilization facilities or facility designs.

Background: Stabilizing Radioactive Waste through Vitrification

Since the initial development of nuclear energy, DOE has accumulated 90 million gallons of high-level radioactive waste in liquid or water-soluble form, mostly from the reprocessing spent nuclear fuel(iv). This waste is both poisonous and radioactive, and must be isolated in order to avoid health and environmental damage. Safe storage is greatly simplified if the waste is reduced in volume and put in a form which can’t leak out of containers and seep through the ground. Waste that is prepared this way is said to be “stabilized” or “immobilized.” A leading technique for stabilization is “vitrificaction”; mixing the waste with molten glass, and then casting it in a metal container.

While vitrified waste is still dangerous, it is dramatically safer than its previous form. Before liquid radioactive waste at DOE’s Hanford facility was moved to newer, double-walled tanks, it is estimated that one million gallons (nearly 2 percent of the total stored there) leaked into local groundwater.(v)Once it is vitrified, it is much smaller (roughly one-quarter its original volume )(vi), and can neither leak, nor can it leach into surrounding water or soil, even if submerged in water.

Schedule and Cost Overruns at DOE Facilities

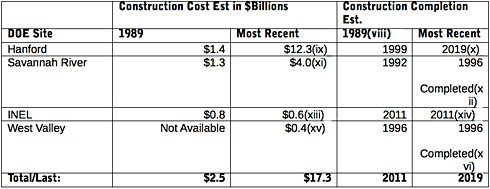

Since the 1980s, DOE has planned to vitrify its 90 million gallons of high-level waste (HLW) using plants built to its own design at four different facilities:(vii) These wastes were supposed to be largely immobilized by now, and completely immobilized by 2028 at a total cost of $2.5 billion. This effort is now expected to take until at least “midcentury,” and the facilities are estimated to cost over $17 billion. This chart shows just how overrun and behind schedule the DOE is in this vital work:

Comparative Progress in Europe

With decades gone by, and billions of dollars spent, the US has not made much progress towards its goal of stabilizing its 90 million gallons of waste.

While there are many differences between the French and US programs, they are similar enough for DOE to have considered adopting French plant designs in 1990. DOE’s objections seemed questionable in 1990 and they seem even more questionable now that 20 more years and billions more dollars have been spent. The facts from France don’t back up their assertions:

The Solution to This Overrun Hazard? Evaluate French and British Options in Parallel With Current US Efforts

With decades of work yet to be done, billions of dollars left to be spent, and the safety of tens of millions of gallons of radioactive waste at stake, it is critical that we evaluate all credible options. It should raise suspicion that technically-savvy, environmentally-conscious nations such as Germany and Japan send their waste overseas to be processed in British and French vitrification plants, while we insist that such options aren’t good enough for us.

Do you like this? Click here to get Truthout stories sent to your inbox every day – free.

My previous report in the late 1980s focused on the possibility of using French designs to build our own vitrification plants. With so much capital already invested in construction of plants to US designs, it seems unrealistic to think that DOE would throw all of that away in favor of re-starting with the French designs. Since the DOE is so much further down the road, I am proposing to “hedge our bets” by spending a small percentage of the remaining budget for building and operating vitrification plants to study the possibility of sending a portion of our waste to Britain and/or France for vitrification. Such an approach would have the following merits:

- A great deal could be learned for a tiny fraction of the remaining budget.

- By putting the job of vitrifying US waste up to bid on an annual basis, we would require DOE to consistently characterize how much waste is left, and what kinds.

- Responses from overseas waste processing contractors such as AREVA (France) and Sellafield Ltd (Britain) would become a matter of public record, providing credible documentation of challenges involved in outsourcing our waste vitrification.

- If either AREVA or Sellafield did submit successful bids, we would be developing a “plan B” in case our operational facility at Savannah River encounters problems, or our other facilities are never completed.

- In the nine years between now and when the Hanford facility is scheduled to come online, we may accumulate a lot of practical knowledge about the unique characteristics of US (waste and have more options as we make plans to use more nuclear energy.

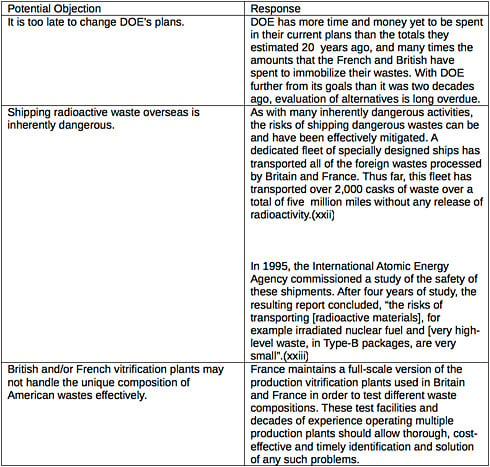

Overcoming Resistance

It seems likely that DOE will resist this proposal, since by definition it challenges their current, long-held plans. I believe such resistance can and should be overcome. The following are examples of potential objections, and suggested refutations:

Conclusion

Stabilization of DOE’s 90 million gallons of radioactive waste is not amenable to simple solutions, but it is also too important to excuse from aggressive scrutiny. Given its track record of ballooning costs and decade-long schedule slips, it seems irresponsible to allow it to continue as business as usual. The challenge is in finding a way to open it up to examination and/or competition that will be manageable and comprehensible to lawmakers and voters. I believe setting aside a small fraction of the budget to invite feasibility studies and bids from our allies may be a way to accomplish this.

Also: Download the 1991 Report,“Cleaning Up Nuclear Waste: Why Is DOE Five Years Behind And Billions Over Budget?,” by Greg Williams.

Footnotes:

i. See p. 12 of “EM Waste Acceptance Product Specification (WAPS) for Vitrified High-Level Waste Form,” July 24, 2008.

ii. Page 2 of “Nuclear Waste: DOE’s Program to Prepare High-Level Radioactive Waste for Final Disposal,” GAO/RCED-90-46FS,1989, indicates that all of Hanford’s high-level wastes (the last of the DOE high-level wastes to be vitrified) would be vitrified by 2008. Now, according to p. 12 of “Nuclear Waste: Foreign Countries’ Approaches to High-Level Waste Storage and Disposal,” RCED-94-172, August 4, 1994. DOE doesn’t anticipate vitrifying this waste before “mid-century.”

iii. See the World Nuclear Association’s June 2009 article, “Radioactive Waste Management,” in which Britain’s Sellafield facility is described as producing 400 canisters per year. See also p.11 of the 2008 French National Report published by France’s Nuclear Energy Agency, which describes the capacity of each of the two plants at La Hague as 550 canisters per year. The plants at Sellafield and La Hague both use the same type of canister, which is described by the plants’ designer, AREVA, as containing 400kg of vitrified waste. These articles put the capacity of France alone at 440 metric tons/year, and Europe as a whole at 1,000 metric tons. Currently, the only facility in production in the US is the Savannah River Defense Waste Processing Facility (DWPF), which, according to “Plutonium Level in Waste to Triple,” The Augusta Chronicle, April 14, 2010, has produced 2,907 canisters in its 15 years of operation. At 2000kg per canister (see p. 3 ofthis), this puts US capacity at 388 metric tons/year.

iv. See p.7 of “Nuclear Waste: DOE’s Program to Prepare High-Level Radioactive Waste for Final Disposal,” GAO/RCED-90-46FS, November 1989.

v. See p. 4 of “Nuclear Waste: DOE’s Program to Prepare High-Level Radioactive Waste for Final Disposal,” GAO/RCED-90-46FS,1989.

vi. See the World Nuclear Association’s June 2009 article, “Radioactive Waste Management.”

vii. See p. 12 of “EM Waste Acceptance Product Specification (WAPS) for Vitrified High-Level Waste Form,” July 24, 2008. Note that the values for waste stored at the various facilities do not add up to the total listed on the same page.

viii. See p.2 of “Nuclear Waste: DOE’s Program to Prepare High-Level Radioactive Waste for Final Disposal,” GAO/RCED-90-46FS, November, 1989.

ix. See p.26 of the “Report to Congress: Status of Environmental Management Initiatives to Accelerate the Reduction of Environmental Risks and Challenges Posed by the Legacy of the Cold War,” January 2009.

x. Ibid.

xi. See p.25 of the “Report to Congress: Status of Environmental Management Initiatives to Accelerate the Reduction of Environmental Risks and Challenges Posed by the Legacy of the Cold War, January 2009.

xii. See p.1 of “Defense Waste Processing Facility Fact Sheet,” 11/2009.

xiii. See p.27 of the “Report to Congress: Status of Environmental Management Initiatives to Accelerate the Reduction of Environmental Risks and Challenges Posed by the Legacy of the Cold War,” January 2009.

xiv. See p.27 of the “Report to Congress: Status of Environmental Management Initiatives to Accelerate the Reduction of Environmental Risks and Challenges Posed by the Legacy of the Cold War,” January 2009. (Note that the facility described here does not address all of the waste covered by the original estimate.)

xv. Ibid.

xvi. See “West Valley Demonstration Project Nuclear Timeline.”

xvii. See p.25 of the “Report to Congress: Status of Environmental Management Initiatives to Accelerate the Reduction of Environmental Risks and Challenges Posed by the Legacy of the Cold War,” January 2009.

xvii. This is the total canisters produced by West Valley and Savannah River (previously cited), multiplied by the 2 metric ton weight of glass per canister (also previously cited).

xix. See p. 3-17 of “Presentation to the energy Ssytems Acquisition Advisory Board on the Status of the Defense Waste Processing Facility,” 12/12/1990.

xx. See also p.11 of the “2008 French National Report” published by France’s Nuclear Energy Agency, which describes the capacity of each of the two plants at La Hague as 550 canisters per year, and 15,000 canisters produced as of 2005. This is multiplied by the 400kg weight of glass per canister, which is described in Return of Vitrified Residues from France to Germany.

xxi. See my earlier report “Cleaning Up Nuclear Waste: Why is DOE Five Years Behind and Billions Over Budget?,” November 1991 for full citations for these DOE objections.

xxii. https://www.pntl.co.uk/about-pntl/default.asp

xxiii. P. 61, “Severity, probability and risk of accidents during maritime transport of radioactive material,” July 2001.

We have 10 days to raise $50,000 — we’re counting on your support!

For those who care about justice, liberation and even the very survival of our species, we must remember our power to take action.

We won’t pretend it’s the only thing you can or should do, but one small step is to pitch in to support Truthout — as one of the last remaining truly independent, nonprofit, reader-funded news platforms, your gift will help keep the facts flowing freely.