Chief Carlos Whitewolf beat a small hand drum and sang a Native American prayer for Mother Earth in the cold January air in Hershey, Pa.

Many of the 50 or so other protesters outside the Hershey Lodge, where national Republican leaders attended a retreat, demonstrated against issues like the Keystone XL pipeline and climate change.

But Whitewolf, chief of the Northern Arawak Tribal Nation of Pennsylvania, was objecting to something more local. In nearby Lancaster County, it’s the Atlantic Sunrise pipeline project.

Whitewolf calls the project “disrespectful” because the pipeline’s current route goes through parts of southwestern Lancaster County rich with ancient Native American artifacts and burial sites.

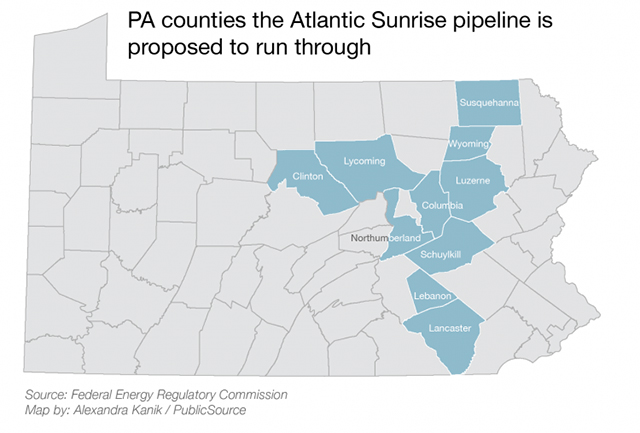

The project is a proposed expansion of a natural gas pipeline that would traverse about 190 miles, through 10 Pennsylvania counties: Lancaster, Columbia, Lebanon, Luzerne, Northumberland, Schuylkill, Susquehanna, Wyoming, Clinton and Lycoming counties.

Opposition has been strongest in Lancaster County, where farmers, environmentalists, Native Americans and others have fought to stop the project since Williams Partners, builders of the pipeline, started the process for approval with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) last Spring.

The resistance to the project echos struggles against natural gas pipelines around the country. At a Jan. 27 National Press Club meeting, FERC Chairman Cheryl LaFleur said gas pipelines face “unprecedented opposition.”

“We have a situation here,” LaFleur said.

If President Obama’s recent Clean Power Plan is to succeed at reducing the output of carbon pollution by the United States, she said, it will need to rely on natural gas and a robust pipeline infrastructure.

That doesn’t bode well for opponents to the Atlantic Sunrise pipeline, who cite concerns including the environment, safety and property values.

But, of all the protests, some see the Native American angle as their best bet to stop the pipeline or get it rerouted.

“The artifacts, the burial sites, the Native American occupation, is the only thing that is federally recognized,” said Robin Maguire, of Conestoga Township. “That is the only thing FERC will listen to. They don’t want to hear how you bought your house for your retirement. They don’t care,” said Maguire, who is part of the Lancaster Against Pipelines group.

It’s normal for pipeline companies to conduct surveys to identify plants, endangered species and environments that might be disturbed in building a pipeline. But going through land important to Native Americans may make the process even more sensitive.

By law, companies must survey land to find items and sites that hold cultural or historical significance. One of those could be Conestoga Indian Town, which many say is the most important Native American site in the state.

If the company finds anything relevant, FERC may require the company to reroute the pipeline, go under items or move them.

“If any sites are found or potentially found to be significant, then either avoidance of the resource or mitigation, such as data recovery, may be warranted,” Tamara Young-Allen, a FERC spokesperson, said in an email.

Data recovery means the company would be required to excavate items, Young-Allen said. Whitewolf and others, are adamantly opposed to this option.

He has vowed that he and other members of the American Indian Movement will block bulldozers and occupy land if the project is approved.

In early January, eight people, including Whitewolf, were arrested after they blocked a Williams crew from conducting test drilling near a Native American site registered with the state.

But the company says all the uproar could be for nothing because the route of the pipeline will change before Williams submits its official application in March, and it could avoid sensitive cultural areas, said Christopher Stockton, a Williams spokesman.

He said Williams is aware of the cultural sensitivity of the area and, as required to by law, is working with the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC) to identify the areas and must follow state and federal protocols for avoiding such sites or finding ways to mitigate disturbance.

“We don’t just put a pipeline somewhere without doing our homework,” Stockton said. And the pipeline would never go through areas where human bones are found, he assured.

Despite what the company says, opponents are skeptical, and they’re using every means to play up the issue, including registering new Native American historical sites with the state.

A Trove of Artifacts

Maguire drives by a scene that’s not unusual in Lancaster County. A group of Amish kids dressed in black play hockey on a frozen pond next to a dairy farm. There’s a slight dusting of snow on green and yellow grass.

“That’s why Native Americans chose to live here,” she said. “Look how beautiful this is.”

She holds a chalky, oval-shaped stone with grooves that she thinks might have been a pestle or a grinder.

Signs protesting the pipeline project are a common sight in southwestern Lancaster County. (Natasha Khan / PublicSource)

Signs protesting the pipeline project are a common sight in southwestern Lancaster County. (Natasha Khan / PublicSource)

For months, she and David Jones, an amateur archaeologist and part of Lancaster Against Pipelines, have asked property owners in the area if they can search their land for artifacts. They’ve found tools, jewelry, weapons.

Archaeologists have said southwestern Lancaster County is a virtual smorgasbord of artifacts because it had the largest Native American settlements in the state.

Read more from our Marcellus Life project!“This is our Machu Picchu,“ said Tim Trussell, a professor of archaeology at Millersville University, in testimony to FERC at an August public meeting. “There is literally nowhere else in the entire state that contains a greater concentration of archaeological sites, features, artifacts or human burials.”

Read more from our Marcellus Life project!“This is our Machu Picchu,“ said Tim Trussell, a professor of archaeology at Millersville University, in testimony to FERC at an August public meeting. “There is literally nowhere else in the entire state that contains a greater concentration of archaeological sites, features, artifacts or human burials.”

Maguire and Jones have managed to find enough material to register eight new historical sites with the PHMC in hopes that their efforts will protect the land from the pipeline’s path.

They’re particularly concerned about the pipeline going through Conestoga Indian Town,an Indian refugee area in the early 18th century. The people were descendants of the Susquehannocks and occupied land reserved for them by William Penn. A famous Susquehannock chief is thought to be buried there.

The tribe was wiped out after members were murdered by the Paxton Boys, a group of maverick frontiersman, in 1763 in what is known as the “Conestoga Massacre.”

Today, there are no federally recognized tribes left in Pennsylvania.

Minimal Impact

People protesting the Atlantic Sunrise pipeline are worried about it going through Conestoga Indian Town, an important Native American site. (Natasha Khan / PublicSource)

People protesting the Atlantic Sunrise pipeline are worried about it going through Conestoga Indian Town, an important Native American site. (Natasha Khan / PublicSource)

Under the National Historic Preservation Act, federal agencies, in this case FERC, must require pipelines be built with minimal impact to historic or culturally relevant sites.

In addition to working with the PHMC to identify these areas, Williams has consulted with archaeologists to conduct shovel tests, digging small holes every 50 feet along the proposed route to look for artifacts.

But Maguire and others complain that those tests don’t go far enough and could miss important historic items.

“It’s just a one-foot hole every 50 feet. It’s nothing,” she said.

Trussell agreed in his testimony.

“Now you may believe that because an archaeological survey is being done prior to construction, any sites and burials on this route can be identified and avoided ahead of time. Unfortunately, this is not at all true,” Trussell said.

When “skulls and femurs are being kicked up” by Williams’ equipment, there will be a “firestorm of public outrage,” he said.

The PHMC regularly reviews Williams plans and surveys for the project, said Howard Pollman, an agency spokesman.

“So far, [Williams] has been re-routing and trying to go around archaeological sites,” Pollman said. “We have been assured they have every intention of going around rather than through Conestoga town.”

FERC and Williams have also contacted federal and state recognized Native American tribes with ties to the area about the project. FERC asked tribes if they have any concerns about it and if they’d submit comments. Problem is, since Pennsylvania has no recognized tribes, none of the Native Americans contacted actually live in Pennsylvania.

Whitewolf, whose tribe is originally from the Caribbean and whose ancestors were relocated to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Cumberland County more than a century ago, was angry because he was not directly contacted.

He and other Native Americans feel it’s their duty to protect the land, bones and artifacts of these people.

“Who else is going to fight for them?” Whitewolf asked.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.