Have national misgivings toward the conflicts after World War II found their way into budgeting for the VA, the agency tasked with caring for those less-fêted soldiers who prosecuted these ill-conceived engagements, or is ideology preventing proper funding of the most efficient US health care system?

Between 2008 and 2011, approximately 210,000 people died from “patient harms associated with [private] hospital care.”

A 2009 study found that 45,000 people die annually from lack of health insurance.

Between Newtown – where 13 children were gunned down by a mentally ill individual – and December 31, 2013, 12,042 people lost their lives to gun violence.

Oh, and 40 veterans died while on a waiting list at the VA.

The VA is a clearinghouse for the casualties of our ill-conceived and violent foreign policy.

Ironically, while all four instances are tragic in their own right, it is the last that has provoked enough pitchfork level rage to shake the halls of Congress and prompt a cabinet level resignation. What accounts for this selective outrage? For the answer, one must dig deeper into the psychological role the Veterans Administration plays in our collective consciousness, a role that goes far beyond its function as a mere provider of health care and rehabilitative services. In truth, the VA is a clearinghouse for the casualties of our ill-conceived and violent foreign policy. Like a beleaguered giant with one hand tied behind its back, it is tasked with putting veterans at the center of a dizzying constellation of services and benefits, even as its every attempt to do so is scrutinized and micro-managed by a culture of tight-fisted, anti-government ideologues unwilling, for decades, to fund it at a level commensurate with its ambitious goal, politicians for whom any government spending is inherently suspicious, profligate and wasteful.

A Ride on the VA Train

The VA train is long, abundantly packed and offers generous assistance to many who have worn a uniform. A federal behemoth, the Veterans Administration offers a range of programs that would be the envy of any low-wage civilian who faces each day without benefits of any kind. In addition to health care, qualified (a word, as we shall see, at the core of many of the VA’s problems) veterans are also entitled to compensation, pensions, educational benefits, vocational rehabilitation, loans and grants for housing, insurance and burial benefits. In 2013, over 24 million veterans and their families took advantage of VA services with an allocated budget, in that fiscal year, of $150 billion. In that same year, VA medical services alone served more than 6.4 million unique patients (a unique patient is a patient who, even if he or she has had multiple visits, is counted only once) at 151 medical centers, 300 vet centers, 827 community-based outpatient clinics, 135 VA community living centers, 6 independent output clinics, 103 residential rehabilitation centers, 225 national and state cemeteries and 56 regional offices.

So what’s the problem?

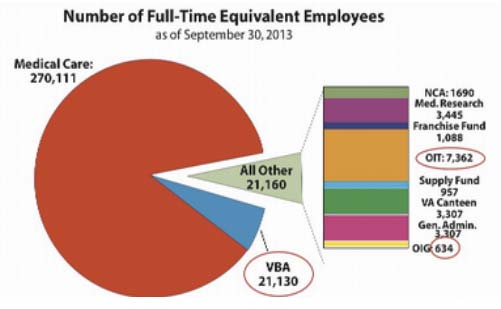

The VA is not monolithic. Extending the railroad metaphor, it runs on two tracks. One – the service delivery system – is the Veterans Health Administration, or VHA. On the other track runs the VBA, or Veterans Benefits Administration. It is arguably more important than its counterpart because it is here that tickets to the VA train are handed out. While the VBA presides over prodigious amounts of money and has the fate of millions of veterans in its hands, the number of its staff charged with approving and handing out the tickets to the VA train is dwarfed by the number of veterans who are lining up each year to request them. One has only to study chart A below (p. 12) to understand that the importance and enormity of the VBA’s task flies in the face of its staffing levels which are much lower than its service component, the VHA:

CHART A

The chart is a stark, visual indication of disparities in VA staffing. A full 86 percent of staffing is dedicated to medical care. Though this is, of course, laudable and well intentioned, that’s a ratio of 12.6 medical personnel to 1 VBA employee, or .07 percent of total VA staff. Though the ratio is roughly similar for the other slice of the pie designated as “All Other,” the level of staffing is particularly small for OIT (Office of Information Technology). These are the tech people who support the crucial electronic network that links the many facets of the VA. At 7,362, it comes in at about .02 percent of total staff.

Many of the present problems at the VA have been attributed to a lack of physicians. Of the more than 270,000 medical service personnel in the chart above, 53,000 are licensed medical practitioners, 14,000 of these are physicians and 1,980 are physician’s assistants. (As of September 2013, the VA was also considering allowing its 3,600 APRNs (advanced practice registered nurses) to operate with less clinical oversight). If one deducts the roughly 7,000 specialty care physicians (i.e., oncologists, psychiatrists, orthopedic surgeons, etc.) who are usually seen only upon referral, we are left with a pool of primary care physicians totaling roughly 8,980 for a unique patient population of more than 6 million. When one considers that the acceptable target panel size (number of patients a doctor can effectively treat in a 12 to 18 month period) deemed acceptable by the VA – or, 1,200 – is equivalent to that of the private sector, we have only to examine the doctor-patient ratios at each clinic to see if this target has been met. These figures are available on a site called “Find the Best” where the numbers for each clinic in the VA system is broken down. With 4.6 doctors per 1,000 visitors, the VA clinic in Palo Alto, California earns the highest, 100 percent rating. However, even the lowest ranked clinic – El Paso, Texas, with 1.8 doctors per 1,000 patients – falls within the accepted private threshold.

Despite the fact that the VA comports with these metrics, the military population it serves suffer from war-related, physical and emotional dysfunction that require more frequent and intense attention. While in the private medical sector, the average yearly visits per patient amount to a little over three, three visits merely scratches the surface for a veteran needing rehabilitative services for a missing limb, or someone beginning one of the extensive protocols required for treatment of PTSD. The fact that veterans must often come back more frequently for treatment would seem to make the private sector panel size unrealistically large. Perhaps one possible remedy for prolonged wait times would be to staff up all VA clinics to the Palo Alto level, a move that would require hiring at least 6,000 more physicians. This, however, is unlikely. Notwithstanding the tight-fisted Congressional opposition that would greet such an idea, given the present vilification of the VA prevalent even in the liberal media, recruiters would be hard pressed to sell young doctors on a career in government service.

The VA is, in fact, a model of efficiency.

Much to the chagrin of many on the right, the VA is a socialized system. It therefore embarks on its mission in the shadow of ax-wielding ideologues anxious for any evidence of what it regards as a socialist economic model inherently inefficient by definition. But the VA is, in fact, a model of efficiency. In his 2007 book, The Best Care Anywhere, author Phillip Longman cites a 2003 study by the “New England Journal of Medicine” that used 11 metrics of care to compare fee for service Medicare with the VA. The study, Longman writes, found the VA’s care to be “significantly better” on all 11 counts. Because the VA has no stockholders, little advertising compared to private sector health care, and physicians who, along with fixed schedules, are freed of the burdensome, extra-medical expenses that come with private practice, the VA’s administrative overhead is extremely low. In 2013, 98 percent of the $150 billion budget “went directly to Veterans in the form of monthly payments of benefits or for direct services such as medical care.” As Longman further avers, “these grievances are about access to the system, not about the quality of care.”

All this quality and all these resources are moot if a vet can’t get in the door and if there are not enough professionals and support staff to handle them. That is a problem, as we have suggested, more quantitative than qualitative. Even before the missions in Iraq and Afghanistan, the number of veterans treated at the VA jumped from 2.9 million in 1996 to 4.5 million in 2003. This is before the legions of physically and mentally wounded were churned out of the Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom campaigns and fed into an already overburdened system. Their numbers, of course, were added to the existing population of veterans from World War II, Korea (an older, sicker population often requiring more care) and the first Gulf War in 1991. By 2015, the VA expects the total number of enrollees to reach 9.1 million, with 6.5 million expected to seek medical care (p. 39).

A hero is a hero, apparently, only in degree.

As early as 1996, the system was showing signs of stress. In response, rather than staffing and funding the agency up to a level sufficient to deal with the growing need after the first Gulf War, Congress reverted to its instinctive, miserly default position and created a meritocratic group system based on eight categories delineated by factors such as theater of conflict, length of service, income of the veteran, and whether injuries were war-related. Dubbed “service connection,” it became clear to any veteran that the extent of any care or compensation would be predicated on where one fell in these priority groups. More significantly, the army of personnel needed to determine which veterans fit where became like a sieve, allowing the river of veterans to pass through to care only in slow trickles. A hero is a hero, apparently, only in degree.

The priority groups were not the only impediment. Funding has long been a logjam obstructing the process. Sponsored by former Rep. Robert Stump (R-Arizona), Public Law No. 104-262, the Eligibility Reform Act, became law on October 9, 1996. According to an explanatory memorandum published two years later, the law principally “amended 38 U.S.C. § 1710 which authorizes VA to furnish hospital care, medical services (i.e., outpatient care), and nursing home care to veterans . . . added a new section, 38 U.S.C. § 1705, directing VA to establish a patient enrollment system to manage the provision of the care and services . . . and directs VA to enroll veterans in accordance with the priorities, in the order listed in the law.”

Veterans were now to navigate through this byzantine gauntlet of categories outlined in the law to determine if they were entitled to care and, if so, how much. However, the mandate came with a big stipulation. Though Subsections 1710(a)(1) and (2) of title 38 directs the secretary to provide medical and hospital care, further on, the law states that the VA “may” (this word italicized in the original) furnish care to these veterans “to the extent resources and facilities are available.” In other words, “you may be entitled to the care, but don’t count on it if the funding isn’t there.” This underscores a crucial difference between a program like Medicare – whose funding is fixed – and the Veterans Administration, whose revenue stream is not. The VA must go each fiscal year with hat in hand and propitiate the gods of funding in the halls of Congress for money to operate. Even the most recent 2015 VA budget for medical services projected by the Obama administration falls $1.4 billion short of veterans’ needs as determined by the Independent Budget Veterans Service Organization (IBVSO), a consortium of 53 veterans’ organization that publishes its own ideal budget each fiscal year.

Veterans were now to navigate through this byzantine gauntlet of categories outlined in the law to determine if they were entitled to care and, if so, how much.

There is no better illustration of the VA’s perilous and politically tainted budget process than the Senate Republicans’ refusal to pass a measure in February 2014 that would have expanded federal health care and education programs for veterans. The $24 billion measure – which would also have created 27 new treatment facilities – would, according to Senate Republicans, “bust the budget.” Their real motive, however, becomes more transparent when one takes into account their thwarted desire to attach language to the legislation tightening sanctions on Iran, something that has nothing to do with veterans. This would seem to illustrate that their professed reverence for those who have served is trumped by their need to stay on good terms with the infinitely more powerful and influential Israel lobby, as well as their desire to use veterans as a political football in the upcoming midterm and presidential elections.

The VBA: Sorting Out the Heroes

As the IBVSO’s report (p. 10) for 2015 recounts, between 2000 and 2013, claims jumped from 600,000 to nearly 1.2 million. But the numbers “tell only part of the story,” the report explains. “The complexity and average number of issues per claim has also risen, further multiplying the workload that the VBA must now process. Over the same period, the VBA workforce grew by just 50 percent.”

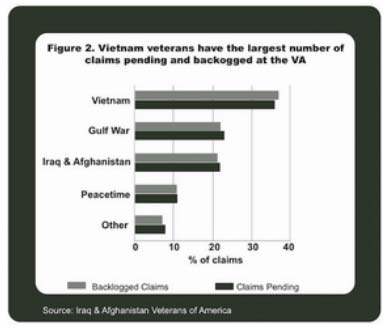

In order to receive disability or benefits of any kind, every vet – no matter what the conflict – must run the VBA gauntlet created by the 1996 Eligibility Reform Act. In a review of its performance in 2013, the VBA states that it “received over 1 million claims for disability benefits and processed 1,169,085 claims.” Seems impressive. But, as an Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America (IAVA) report suggests, it merely scratches the surface. The number of claims tripled between 2009 and 2012 alone – two-thirds of which were backlogged. “By January 2013,” the report says, “the number of pending disability claims was over 900,000 with over 600,000 – or nearly 70 percent – pending longer than 125 days.” Chart B below is instructive in that it shows the distribution of backlogged claims across the veteran population.

CHART B

As the chart shows, most of the pending and backlogged claims are from Vietnam veterans who, now in their later years, are experiencing more health issues and seeking care and compensation formerly unavailable. But they are only one of the multiple streams from every conflict – as far back as World War II – inundating workers at the Veterans Benefits Administration who must painstakingly gather VHA and Defense Department medical records, service records, income and occupational information, and mitigating circumstances of the conflict including, but not limited to such factors (prescribed by the priority groups) as who was exposed to “chemical, nuclear, or biological agents,” who was a prisoner of war, who is disabled, who isn’t, who has other insurance . . . and the list goes on. Encumbered by reams of data, VBA staff must decide the fate of veterans and assign them a disability rating ranging from 10 percent to 100 percent “service connected,” with each range rewarded successively more compensation.

The actual average time to process a claim is well over 300 days.

Though former Secretary of the VA Eric Shinseki assigned a target goal of 125 days to complete the claims process in 2009, the actual average time to process a claim is well over 300 days. And, of course, many of these decisions are thrown back on the heap as appeals. (As of December 2013, there were 265,000 claims in appeal.) To address the backlog on disability claims, Secretary Shinseki implemented an aggressive campaign to deal with it in April 2013. Dubbed “oldest claims first,” it attempted to deal with the claims more than two years old through a creative use of staffing, technology and streamlining the process. After heroic efforts toward the goal, the VA proudly announced in September 2013 that it had reduced the number of backlogged claims to the “lowest since 2010.” That “lowest” number was 722,013. When one considers that it takes an average 300 days to process each claim, the work yet to do is sobering.

Little will change at either branch of the VA until staffing and funding levels are brought in line with its daunting mission, and sufficient resources are provided to ensure that performance is gauged more against qualitative rather than quantitative standards.

One factor driving the reduction in the number of pending claims from 860,000 at the beginning of 2013 down to about 685,000 (about 20 percent) in January 2014 was a perilously human one: mandatory overtime. This, of course, was unsustainable and the practice was ended just before Thanksgiving in 2013 (p. 11). Processing ground nearly to a halt during the government shutdown. Even the 5,000 full-time equivalent employees (FTEEs) that had been hired between 2008 and 2012 were not enough to tip the balance appreciably. Since then, the number of new hires has fluctuated between 500 and 600 FTEEs, a laughable amount considering the task at hand (p. 7).

In addition, the IAVA report chronicles problems in VBA employee training:

Our VBA members continue to report problems with the quality of training for the increasingly complex jobs of developing and deciding claims for disability, pensions and other benefits. New employees are rushed into production without adequate on-the-job mentoring. VBA continues to overemphasize online training in lieu of classroom training that deprives new and experienced employees of sufficient time and guidance to fully comprehend new complex concepts. In addition, many of the managers who provide training and mentoring at the VBA regional offices (ROs) lack the experience or expertise to train and mentor front line employees. (p. 22)

Much as those on the right would strenuously disagree, we can assume from the above that little will change at either branch of the VA until staffing and funding levels are brought in line with its daunting mission, and sufficient resources are provided to ensure that performance is gauged more against qualitative rather than quantitative standards.

The Phoenix VA: Something Evil a-Foote?

On its slow march to hell, the path of good intentions recently took a detour through the Phoenix VA at the behest of Dr. Sam Foote, the now lionized VA whistleblower. (It is noteworthy that the 40 veterans at issue represent roughly .000008 percent of the more than 53,000 unique patients successfully served by facilities in Maricopa County, Arizona, of which the Phoenix facility is a part. It has also not been officially ascertained that their deaths were directly related to lack of care.) Foote’s government pension now safely secured, he has parked his retirement lawn chair by the VA fishbowl and is, with much fanfare, shooting at the fish inside on the rather confusing pretense of helping them. Leaving aside the good doctor’s motives, when we get down to the details of the allegations, the frenzied exploitation by the media and the right wing, and what seems to be a monumental lack of good judgment on his part in choosing CNN (ravenous for any scandal to bump its ratings) and FOX News (anathema to any entity whose name begins with “Department of”), Dr. Foote has, it seems, unwittingly chosen to recruit the very enemies of the Veterans Administration in his cause to reform it. Let’s review the gist of his allegations.

What ails the VA is not a matter of sins, but systems.

Allegedly, the whole nefarious operation begins when a vet comes in to make an appointment -whereupon, according to Foote, “they enter information into the computer and do a screen capture hard copy printout. They then do not save what was put into the computer so there’s no record that you were ever here.” After this purported act of administrative subterfuge, the hard copy generated “that has the patient demographic information is then taken and placed onto a secret electronic waiting list, and then the data that is on that paper is shredded.” Tracks now hidden, Foote alleges, administrators have only to wait until an appointment within the specified 14 to 30 day window becomes available. A new date, he asserts, is then registered as the initial request date, even though the actual time the vet appeared may be weeks or months gone by. Then, voilà! The fabricated numbers are presented to Washington as evidence of a job on time, well done. In a nutshell, according to Foote: a) The veteran appears, asks for an appointment and is not, as in the past, assigned an initial appointment, no matter how far out. He or she is, instead, b) entered onto a secret electronic list that lays fiendishly silent and dormant while any paper copy bearing the patient’s info is fed to the shredder.

Dr. Foote had, apparently, been amassing evidence of the supposed cabal a full year before his retirement and went to the media only after letters, he asserts, sent to government officials went unanswered. One ostensibly unresponsive official was Rep. Ann Kirkpatrick (D-Arizona) who, according to her office, did in fact reply to Foote, offering him a conference call about the allegations. However, this offer was withdrawn, says Kirkpatrick’s spokeswoman Jennifer Johnson, once her office learned that the allegations were under investigation by the Office of the Inspector General.

Delving into the heart of the controversy, it is important to ask both why and how information was misrepresented. In our rush to wrap our arms around those veterans we so desperately need to reassure ourselves of our own exceptionalism and patriotism, we instinctively construe any threat to them as a moral – even criminal – assault. What ails the VA is not a matter of sins, but systems. Rather than a clear-eyed look at ill-advised goals, overworked and outdated programs, insufficient resources and low-level personnel saddled with impossible tasks, it makes for better headlines – and is certainly more politically advantageous – to see conspiring administrators pursuing a rogue agenda, manipulating “secret lists,” and craven clerks anxious to do any heinous thing to ensure their next bonus. So what comes next? What happens after a hundred – a thousand – VA employees are sacked or even jailed for simply driving an overloaded, lumbering car? The car remains, of course, and it remains just as overburdened and in need of relief.

When you’re done, imagine a newly minted, low-level government clerk – on the job for the first time – confronted with entering anything into this monster while answering phones and tending to clerical business, and you’ll be a little closer to the real problem at the VA.

The system in question, the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture, or VistA, has, since its inception in the late 1970s, been the electronic backbone supporting the Veterans Administration. Its ability to track every aspect of patient care, from diagnoses to dosages is unique to the VA, has no counterpart in the private sector, and is, in great part, the reason the VHA is indeed, as author Phillip Longman suggests, unrivaled in quality of care. Like branches on a tree, VistA is a network of 20,000 programs that work together. Created by doctors for doctors working in their free time, its language is simple, non-proprietary and flexible. But, with many more conflicts since its inception, and many more veterans piling on, its branches are straining under the heavy load.

The scheduling component of VistA was conceived in 2002. Its manual was recently dusted off and revised in March 2014. To get an idea of what VistA scheduling attempts to do (and, in so doing, walk in the shoes of any VA employee tasked with using it), grab a big mug of coffee and settle in for a riveting read. Available online, the 102-page tome details every possible scheduling scenario, taking into account group listing, veteran requests, doctors’ recommendations and just about any other eventuality. When you’re done, imagine a newly minted, low-level government clerk – on the job for the first time – confronted with entering anything into this monster while answering phones and tending to clerical business, and you’ll be a little closer to the real problem at the VA.

For all its shortcomings, the scheduling component of VistA has nevertheless been the accepted tool at the VA for assigning appointments and gauging wait times. The root of the system, like zero on a number line, is the “direct date.” This is, theoretically, the date of the initial visit requested either by the provider or the veteran. For the system to function properly, this direct date must be accurately and firmly locked into the program after the initial contact so that subsequent visits can be accurately assigned, altered or substituted according to priority, availability and urgency. All bets are off if this date is somehow recorded improperly or even lost in the system because, for instance, someone doesn’t know how to use it, or, in frustration, starts making separate lists in an ill-advised attempt to keep track. If the direct date disappears, then zero, analogously, disappears from the number line until the next point of contact – perhaps months later – when it is picked up and assigned as the new, albeit incorrect and belated, direct date.

What wasn’t found were shredders secreted in some back room, overflowing with the engorged evidence of bureaucratic malfeasance.

VistA was, it seems, the diabolical electronic waiting list Dr. Foote was referring to in his interview with CNN. “They started this secret list in February of 2013,” Foote asserts. “At some time, they changed over from paper to electronic, in early summer, maybe approximately June or July. And transferred names over to the electronic waiting list.”

In the same CNN piece, then chief of staff at the Phoenix facility, Dr. Darren Deering, describes the event from his own perspective:

So what we did is we took those patients that were scheduled way out into the future, and we put them on this national tool that the VA uses so that we could track them. What that did is, rather than having an appointment 14 months out into the future, it put them on this EWL electronic waiting list, so that when we had an appointment that came open, so if a veteran called next week and canceled their appointment, we could pull a veteran off this list and get them into that slot.

So it actually improved the probability of these veterans getting an appointment sooner. And in that transition time, I think there was some confusion among staff; I think there were some folks who did not understand that, and I think that’s where these allegations are coming from.

Though subsequent investigations have indeed corroborated excessive wait times, delays were attributed primarily to factors such as poor training, high turnover, insufficient phone help and technology in need of updates. What wasn’t found were shredders secreted in some back room, overflowing with the engorged evidence of bureaucratic malfeasance. Yes, humans are responsible for problems at the VA: humans afraid of their bosses, afraid to lose their government jobs, and anxious to fulfill the department’s unrealistic mission, even with inefficient tools and a shortage of personnel.

Taking Stock in the Spare Room

Most everybody has one: that proverbial spot in the corner of the home where odds and ends, unused gifts, empty picture frames and broken appliances are secreted from the eyes of visitors and exiled, momentarily, from our attention. It’s that place where we hurriedly store papers in an awkward pile in those harried moments before unexpected company arrives. These are things, we tell ourselves, too valuable to cast aside, but not relevant enough – at least for now – to be set to some useful purpose. There they sit, in that limbo between usefulness and recycled refuse, half cared for, half forgotten. And so it goes with the Veterans Administration, a massive repository for the damaged and abandoned survivors of our nation’s too frequent need, since Vietnam, to reaffirm our cultural relevance at the point of a gun.

One has only to take a brief look at the historical budget of the Veterans Administration to appreciate, in numbers, our changing attitudes toward veterans and the conflicts they were in.

We say we love them, revere them – our veterans – and stumble over ourselves to see who can be the most effusive in worshipful praise and set them above other equally needy citizens who have not worn a uniform. But the chasm between rhetoric and reality soon deepens when we get into that big room that is the Veterans Administration and start making judgments about who’s more valuable than whom, and who will pay. In Political Science 101, one learns that a budget is a moral document, a reflection in sums and subsidies, of what a government truly values. One has only to take a brief look at the historical budget of the Veterans Administration to appreciate, in numbers, our changing attitudes toward veterans and the conflicts they were in.

In 1945, at the end of World War II, there was a flood of money into the VA and a celebratory feeling unrivalled to this day. The VA’s budget jumped from $1.5 billion in 1945 to $4.8 billion in 1946, then to $8.4 billion in 1947. Veterans took off their uniforms at the end of the “Good War” and entered a healthy post-war economy. They were neither vetted nor sorted into categories to determine who would enjoy the benefits of a GI Bill that would pay for their college educations, subsidize their homes and provide the seed money for a stable middle class. That math changed during and after Vietnam. As the ugly, divisive and questionable moral nature of the war unfolded over many years, the VA budget increased only in small increments until the early 2000s, averaging only about a couple billion each fiscal year. It is fair to ask, then: Have our national misgivings toward the conflicts after World War II somehow found their way into budgeting for the VA, the agency tasked with caring for those less-fêted soldiers who prosecuted these ill-conceived engagements?

Lumbering and all embracing, the VA is a big target – easy to bash. For many years it has taken the punches from its detractors, then moved on to absorb even more of the veterans we, as a culture, can’t seem to stop producing. But Phoenix may have changed that. Rather than funding appropriate staff and resources to correct the problem, recent legislation proposes to “fix” the system by subcontracting care to private facilities, a move that will compromise the traditional self-contained nature of the VA and cripple its efficiencies in the vise of market-oriented, profit-driven private health care.

So, if the VA is so incompetent, riddled with corruption and incapable of fulfilling its mission, then go for it: privatize it. Hand out the vouchers to the men and women in the residences, the vet centers and under the bridges and see just how far that voucher will go in the private sector. See if all stockholders at United Health Care, Blue Cross and Humana – who no doubt love the vets so much (“thank you for your service”) – will countenance the same extensive wrap-around services, multiple visits and cross network referrals, even when doing so starts cutting into the bottom line and compromising their standing on the big boards on Wall Street.

It’s time to go into the big back room that is the VA and take inventory, to take stock of what is truly valuable and either make a commitment to sustain it with the resources it deserves, or let it collapse under its own weight. But that would be a tragedy, because a model for the affordable, efficient health care we’re now struggling to implement in the private health care arena has already existed for decades, and it’s called the Veterans Administration.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $17,000 by midnight tonight. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.