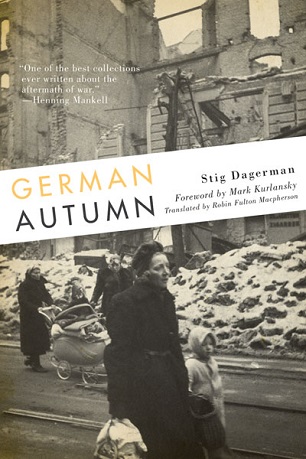

Stig Dagerman wrote about the resigned, mechanical hopelessness of post-World War II Germany back in 1947, but his book German Autumn still manages to resonate with readers more than 60 years later.

He writes, “Reality doesn’t begin to exist until the historian has put it into its context and then it’s too late to experience it, and vex over it, or weep. To be real, reality must be old.”

But even though the events of Dagerman’s book are now an old reality, his writing shows us that it’s not too late to experience and weep over the reality of the war-ravaged country. German Autumn is a collection of articles he wrote about his travels to Germany in 1946 that has now been translated into English for the first time. It reveals German citizens’ daily life up close as they struggle to live in a country attempting to pull itself together amidst the rubble of war.

“Someone wakens,” Dagerman writes in the opening pages of the book. “If she has slept at all, freezing in a bed without blankets, and wades over the ankles in cold water to the stove and tries to coax some fire out of some sour branches from a bombed tree.”

Though Dagerman claims that “their whole manner of living is indescribable,” he is a master of language and uses a gentle lyricism to craft images that take the reader back in time until it feels as though they, too, are standing in ankle-deep frigid water trying to get a fire going long enough to bring some fleeting warmth to a freezing cellar.

Dagerman’s poetic syntax, coupled with the destruction he depicts, creates a jarring juxtaposition of relaxed uneasiness as the reader progresses through the book.

“Cologne’s three bridges have spent the last two years submerged in the Rhine, and the cathedral looms melancholy, sooty and alone in a pile of rubble with a fresh wound along one side which seems to bleed at twilight.”

Despite the soft way the decrepit scene is described, he captures the reality of destruction in “fresh wound.” He relates witnessing other journalists interviewing families who wake to a numbing cold and a gnawing hunger about whether they were better off under Hitler. He reports on the families “stooping with rage, nausea, and contempt” as they give the politically incorrect answer: “Yes.”

“If you ask someone starving on two slices of bread per day if he was better off when he was starving on five you will doubtless get the same answer. Each analysis of the ideological position of the German people during this difficult autumn will be deeply misleading if it does not at the same time convey a sufficiently indelible picture of the milieu, of the way of life to which these human beings under analysis were condemned.”

Dagerman’s ability to balance this analysis with atmospheric description is what makes this book stand out from others on similar topics. But beyond the language and imagery, German Autumn’s shining attribute is the way it makes the reader think. Dagerman’s journalism training makes for a straightforward reporting of the scenery around him, which allows readers the chance to decide for themselves what’s meaningful about what is presented on the page. Whenever an author trusts the reader to this extent, it makes for an intelligent discourse between reader and text and enhances the experience. A reader from 1947 can take out of the book what he will, and a reader from 2013 can derive a whole other meaning although the words have never changed. The book continues to resonate for new generations as it portrays events that have repeated throughout history and continue today.

The same themes that are played out in our world today are evident in postwar Germany as well. Dagerman writes how the “one percent of the German ‘quality’ were Nazis.” This moment of clarity brings forth a rush of feelings about our own one percent today: Though they come with a different title, they still exist.

“Our lords and masters may change,” an old woman tells Dagerman as they ride in the darkness of a boarded-up train. “But it’s always us who get stuck in the middle.”

Additionally, Dagerman illustrates the plight of the young people of Germany, many of whom are drifting into uncertainty postwar. It’s similar to what our youth experience today as they are simultaneously targeted and disenfranchised based on their age, all while not being trusted with responsibility or being blamed for things they had little control over.

Dagerman writes, “Within the parties and the unions young people are fighting their elders in a vain struggle for influence, which the older generations will not hand over to the younger, who, they say, have grown up in the shadow of the swastika, and which the younger in their turn will not entrust to the older who, they say, bear the responsibility for the collapse of the old democracy.”

This mistrust of the youth and the youth mistrusting the generation before them is reminiscent of our culture today, which blames the youth population for being apathetic (despite evidence to the contrary such as the Occupy movement), and a youth generation that lambastes the previous generation for leaving them with a corrupted system to work their way out from under.

Dagerman’s book serves as a snapshot of the chaos and turmoil affecting postwar Germany, and also serves a mirror reflecting our own culture, years later. It’s important that this book has finally been translated into English so a whole new culture of people can glimpse the life of the war-torn and afflicted; not only to change the future but to also clarify the past. As Karl Jaspers, the German psychiatrist turned philosopher once wrote, “We wish to understand history as a whole, in order to understand ourselves.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $47,000 in the next 8 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.