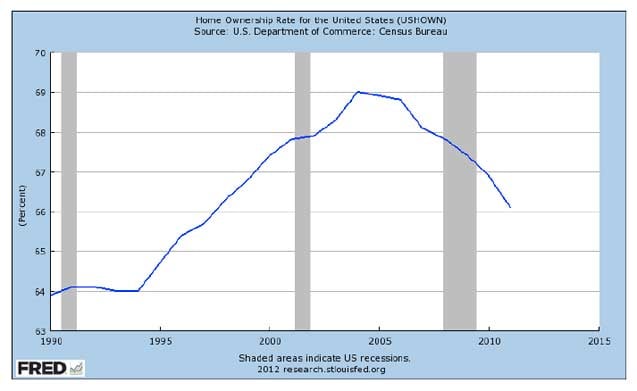

The financial crisis of 2008 was terrible for homeowners saddled with heavy mortgage payments, especially the millions of low-income, first-time buyers who were tempted to buy in with deceptive loans during the height of the housing bubble. About 4 million foreclosures have been completed since the financial crisis of 2008, according to CoreLogic, a data provider to the real estate industry. Since 2006, when subprime loans first began to default in large numbers, there have been 9.4 million foreclosures initiated, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (US Fed). To a select group of hedge fund and investment bankers the financial crisis that pivoted on these foreclosures was the opportunity of a lifetime. They made billions from the crash by wagering against the stability of the US housing market.

Now some of the same elite investors are tacking backward and betting on a recovery of the housing market. It’s a strange recovery though, propelled not so much by families seeking their own piece of the American dream, but instead by the US Fed’s monetary policies. Low-interest rates fostered by the Fed are causing big-money investors to purchase foreclosed single-family homes in blocks of hundreds, even thousands. Expected gains in home prices are also leading hedge funds and investment bank traders to gamble on housing derivatives.

Like the so-called jobless recovery, characterized by rising business earnings in the midst of high unemployment, the nascent housing recovery is not propelled by a rise in homeownership rates, employment and incomes. Instead, foreclosure rates remain high, as does do unemployment figures, and there’s a big backlog of bank-owned properties that has yet to hit the market. Meanwhile, many former home owners have been relegated to the status of renters. If home prices are truly embarked on a sustained rise, the big gains in any new equity created will likely accrue to a smaller number of owners, many of them corporate investor-landlords, and to a few elite financial speculators positioned to make complex derivatives bets on housing bonds. That’s how it’s playing out so far.

2007’s “Big Short”

To understand the current dynamics in the housing market, it helps to go back in time just before the crash. The collapse of the US housing market was the catalyst of the global financial crisis of 2008, and the root source of the last five years of economic stagnation. It was skyrocketing real estate prices that facilitated the inflation of the largest debt bubble in history, allowing Americans to take out unsustainable consumer loans so long as the equity in their homes grew. The bubble burst because real wages continued to decline, total consumer debts continued to grow, and many of Wall Street’s derivative innovations turned out to be cynical products designed merely to package up unsustainable obligations and offload them onto some other sucker’s books. The rest is history. Millions were foreclosed on, and the economy hemorrhaged jobs.

A few prescient investors saw it coming and wagered that the US housing market would collapse. They made billions on that bet, literally sucking money from the accounts their counterparties – banks and insurance companies who believed that a decline in home prices across all US regions was impossible.

The mechanics of the bet were conceptually simple, if technically complex: Bearish speculators identified mortgage bonds they thought were toxic, comprised of thousands of individual home loans that were sure to default if interest rates rose or if the unprecedented rise in home prices even just slowed a little. These few contrarian investors then purchased credit default swap (CDS) contracts, synthetic derivative products created to insure an investor against the possibility of defaulting mortgage bonds.

CDSs had two sides, the buyer and seller, and involved a zero sum wager. If homeowners continued to make payments on subprime mortgages, then the buyer of CDS insurance merely paid out a small premium each year. However, if the market stumbled and mortgages within the bonds that comprised larger mortgage-backed securities began to default in large numbers, then the seller of the CDS would owe huge sums of money to the buyer.

Author Michael Lewis called this the “Big Short” in his book of the same title because it involved a monumental short-selling strategy. Derivatives made short-selling a strategic possibility with the new multi-trillion-dollar global market of US mortgage credit. Investors had no need to actually own subprime mortgaged bonds, or to borrow these assets, as is traditionally required in the short-selling strategies of the pre-derivatives revolution. Instead, an investor could “synthetically gain exposure” to subprime risk, as they say in Wall Street parlance, simply by entering into a free-standing swap contract with a willing counterparty.

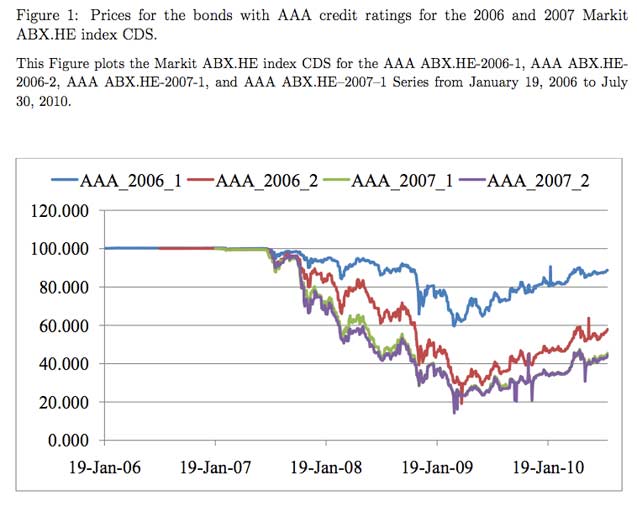

Another popular means of shorting housing was to make directional bets on the price of subprime mortgage-backed securities through the ABX.HE Index. “ABX” stands for asset-backed security, and “HE” stands for home equity, denoting to an investor that the index tracks the value of credit default swaps tied to subprime mortgage bond securities. The biggest investment banks involved in creating subprime mortgage-backed securities like collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs) and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) created the ABX.HE Index in 2006, just in time for short-sellers to game it to their advantage.

A managing director at Goldman Sachs, one of the firms instrumental in launching the ABX.HE Index, explained that it was designed to provide investors with “a simple and efficient way to gain or hedge exposure to home equity asset-backed securities.” This was the official story the banks told regulators and their customers. The Index, they claimed, was to be used to prudently insure actual investments in mortgage-backed securities.

Like other derivatives, however, the ABX.HE would actually become a tool for highly leveraged speculation by hedge funds, many of which had no real holdings of the housing assets from which the indices’ value and cash flows derived. One could simply enter into a trade requiring the exchange of cash flows that changed depending on the value of referenced securities, in this case, the value of credit default swaps tied to subprime debt that was only financially viable if home prices continued to rise and create homeowner equity.

After news began to spread within Wall Street’s upper echelons that subprime mortgage bonds were beginning to turn sour, more and more traders sought ways to bet against the entire market. Goldman Sachs quickly used the ABX.HE to establish short positions for the bank’s proprietary funds, and for several favored clients.

According to Richard Stanton and Nancy Wallace, scholars at the UC Berkeley Haas Business School who have studied pricing and trade patterns of credit derivatives, “trading in the ABX.HE index CDS delivered two of the largest pay-outs in the history of financial markets: The Paulson & Co. series of funds secured $12 billion in profits from a single trade in 2007; and Goldman Sachs generated nearly $6 billion in profits (erasing $1.5 to $2.0 billion of losses on their $10 billion subprime holdings) in 2007.”

Goldman Sachs’ and Paulson & Co.’s earnings became the source of an investigation by the SEC. The bank created subprime mortgage-backed securities and sold them to several German banks, but then, along with the Paulson & Co. hedge fund, bet against these very same securities. The SEC fined Goldman Sachs $550 million (a mere fraction of the profits). Paulson & Co. paid no such fine and admitted no wrongdoing.

Other beneficiaries of the foreclosure crisis included Kyle Bass, the Dallas hedge fund manager who also shorted subprime mortgage-backed assets using credit default swaps. Bass’s Hayman Capital reportedly reaped half a billion dollars.

Greg Lippman, a trader with Deutsche Bank in 2006, pestered dozens of hedge funds and other wealthy investors in a sales blitz to convince clients on his similarly designed bet to short US home prices. According to Michael Lewis, who interviewed dozens of people who put on the “big short” trade, Lippmann had distilled his strategy into a data-rich presentation titled “Shorting Home Equity Mezzanine Tranches.”

All of the derivative tools used by speculators to short the market before the financial crisis still exist. Few regulatory changes were made to reign in this kind of high-stakes gambling using the synthetic exposure of derivatives, indices and short-selling techniques.

Fed Creates Opportunities to “Go Long”

Like the jobless recovery in corporate profits that began in 2010, the housing market’s current recovery is characterized by rebounds in securities prices that do not necessarily reflect any widely shared economic improvements for most Americans. Instead, the recovery seems to be propelled by federal monetary policy.

The US Federal Reserve’s purchase of billions of mortgage-backed securities is most responsible for the nascent housing recovery, say many analysts. The Fed has committed to buying upwards of $40 billion a month into 2015 (totaling anywhere from $480 to $960 billion) in mortgage-backed securities. The effect of the Fed’s purchases is to drive up the price of mortgage bonds, which inversely reduces the yields on the bonds, and eases credit, theoretically making home loans cheaper and inducing more prospective home buyers to dive into the market. That’s the logic the Fed’s board is ostensibly using at least.

Home prices have decidedly responded. The Case-Shiller Index, which tracks changes in home values in major cities, showed definite increases in year-over-year values from 2011 to 2012. CoreLogic’s Home Price Index showed a similar rise, with home values up more than 6 percent in October 2012, compared with the prior year.

Skepticism abounds, however. “The reality is that quantitative easing (QE) has made it cheaper for the government to borrow, has artificially propped up the housing market (making it take longer to recover) and has dramatically manipulated the distribution of capital in financial markets,” said Anthony Randazzo, director of economic research at the Reason Foundation. “And the economy has not been in recovery.” Randazzo said the Fed’s mortgage-backed securities purchases are mostly benefitting the top 10 percent of Americans who own the bonds and stocks that are rising in price as a result of the Fed’s purchases.

Even economists within the Federal Reserve are noting that while the government’s mortgage securities purchases are lifting home prices, they are not necessarily helping the average American buy a house. Michael Bauer of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco noted in a May 2012 report, “The link between rates on mortgage-backed securities and actual mortgage rates has weakened in the wake of the financial crisis.” In other words, the Fed’s ability to stimulate lending and get houses into the hands of individual home buyers isn’t working as planned, but still home prices are rising.

Foreclosure to Rental Mills

There are buyers ready and able to take advantage of the Fed’s macro-economic influence on home prices: large investors seeking to buy up what they’ve identified as a “new asset class,” single-family residential homes in select suburban housing markets.

Some of these companies have already amassed portfolios of thousands of foreclosed and short-sale homes at historically low prices and are busy converting them into rentals. The eventual increase in the value of these homes is an added enticement. Projected yields are high enough to justify purchases of single-family homes as an asset that will inflate greatly in value. If prices continue to increase, private equity buyers could hold the properties for a few years and then make an “exit,” as they say in the industry, and book a big profit.

Some companies like WayPoint of Oakland, California, already own portfolios of thousands of homes purchased at dramatically low prices, most of them obtained after heavily indebted owners were forced to abandon them. WayPoint’s holdings are concentrated in the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Chicago and Atlanta, according to the company’s web site. Menlo Park private equity firm GI Partners has committed over $1 billion to fund Waypoint’s expansion.

Others have copied WayPoint’s foreclosure-to-rental model and are buying up tens of thousands of distressed properties across the US to convert vast stocks of residential homes into rental housing. The Blackstone Group private equity fund has already spent $1 billion to buy up over 6,500 single family homes in multiple markets, assembling these into what the firm is calling its “single-family rental home platform.” In a public relations video Blackstone created for its real estate management company, Invitation Homes, the firm’s head of global real estate, Jon Gray, says, “I think at its heart we’re making a bet on America with this investment strategy. We’re betting that housing prices are going to begin to recover.”

McKinley Capital, another Oakland private equity real estate investor, is buying foreclosed single family homes at prices discounted up to 80 percent of their 2006 high in California’s hard-hit Central Valley. “McKinley plans to resell the houses in about five years for double what it paid and is targeting 20 percent annualized returns for its investors, which include wealthy individuals,” according to a report in the Wall Street Journal on the foreclosure-to-rental business.

Another foreclosure-to-rental mill, Silver Bay Realty Trust, described its business strategy in a December 2012 prospectus issued to investors: “As the housing market recovers and the cost of residential real estate increases, so should the underlying value of our assets. We believe that rental rates will also increase in such a recovery due to the strong correlation between home prices and rents. This trend also leads us to believe that the single-family residential asset class will serve as a natural hedge to inflation. As a result, we believe we are well positioned for the current economic environment and for a housing market recovery.”

Silver Bay owns more than 2,450 houses and plans to invest a quarter-billion dollars to obtain another 3,100 homes in Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Nevada, North Carolina and Texas, according to the company’s SEC filings.

Mike Orr, director of the Center for Real Estate Theory and Practice at Arizona State University’s Carey School of Business, reported investors are buying up as much as a third of the homes selling in the greater Phoenix market today. “I know of a normal home that recently received 95 written offers, 51 from investors and 44 from owner occupiers,” said Orr. “You can take away the 51 investors, and you still have 44 owner occupiers trying to buy one home. However, investors are buying with cash, so they usually win these competitive situations, leaving owner occupier buyers frustrated.” Orr believes that the presence of investors is causing prices to rise in Phoenix because of their buying power.

Atlanta Realtor Bruce Ailion also believes investors are not just responding to the Fed’s stimulus, but that the presence of large investors is further increasing home prices. “In my market, private equity and hedge funds are driving up prices,” Ailion recently told reporters with CBS News.

The end result is that many housing markets have already consolidated around fewer landlord-owners and an increased number of renters whose economic situations still prevent them from buying a home.

Derivatives Bets on the Recovery

Some of these same speculators who shorted subprime housing debt in 2006 and 2007 have already tacked a complete opposite bet, expecting home prices to rise due to the Fed’s mortgage bond purchases. Investors like former Goldman Sachs trader Josh Birnbaum, who now runs the Tilden Park hedge fund, are telling clients to put their money behind subprime mortgage bonds, many of which are rising in value. According to a recent Bloomberg News report, Birnbaum’s firm is posting a 30 percent gain in 2012, mostly from bets favoring price increases in subprime mortgage bonds that lost upwards of 80 percent of their value during the financial crisis.

Birnbaum was one of the architects of Goldman Sachs’ big short bet against subprime housing in 2006 through the ABX.HE Index. According to William Cohan, author of Money and Power: How Goldman Sachs Came to Rule the World, Birnbaum quit the investment bank after a $10 million bonus check left him feeling shorted for putting on the firm’s big short bet. Birnbaum’s hedge fund is reportedly using the same index this time around to gain the opposite kind of exposure to housing debt.

Joining Birnbaum’s hedge fund in this strategy is John Paulson’s firm, Paulson & Co., which posted the biggest gains of all thanks to the housing meltdown five years ago. Paulson’s fund reportedly began buying housing mortgage securities back in 2008 and 2009, just after they’d collapsed in price.

In a letter to his investors earlier this year, Kyle Bass of Hayman Capital wrote that, with respect to subprime housing debt, “the stars are aligned for a continued recovery of this asset class today.” Bass told reporters recently that more than half of Hayman Capital’s funds are currently invested in subprime mortgage bets.

Greg Lippmann, the architect of Deutsche Bank’s $1.5 billion big short bet, is now running a hedge fund that is going long on US subprime debt. Libremax Capital, which is said to manage about half a billion dollars, mostly sourced from wealthy investors, is said to be investing in subprime mortgage bonds of early 2005 “vintages,” which have already purged many of the delinquent debts from their rolls. “We believe securitized [home mortgage] products are fundamentally cheap to broader markets,” Lippman told reporters last year when asked about his fund’s strategy.

The biggest hedge fund winner in 2012 is the New York-based Metacapital. Its “Mortgage Opportunities Fund” has squeezed a 520 percent profit on the year by betting on housing price increases owing to the Fed’s purchase of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac mortgage bonds.

A Home Owner-less Housing Recovery?

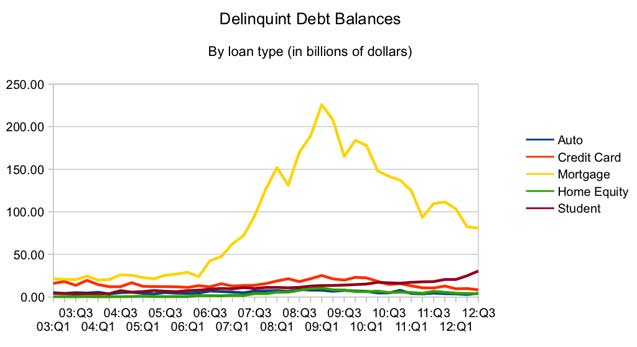

According to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, homeownership rates have plummeted by 3 percent nationally since 2004, falling to a low not seen since the mid-1990s. The backlog of delinquent mortgage loans and in-process foreclosures means that millions more will lose their homes and become renters, couch-surfers or homeless in the next few years.

While the foreclosure rate may be dropping nationally, it remains extremely high compared to historical averages. Approximately 186,000 homes, or one in every 706 units of housing, were foreclosed on in October, 2012. There have been about 5 million bank repossessions of housing between 2006 and 2012, according to RealtyTrac.

According to economists with the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, only 10 percent of homeowners who lose their houses because of default on mortgage payments will regain access to mortgage markets in the next 10 years. This means that there are now millions of Americans who will be closed out of the housing market during not only this peculiar recovery phase, characterized by a rise in prices and private equity buyers acquiring much of the inventory, but also down the road, long after houses have regained much of their value.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.