The US military aircraft carrying the cargo is only used for missions like this.

Muhammed Farhan Latif and other members of his family waited at a gatehouse at Al-Dailami Air Base in Sana’a, Yemen’s capital, for the plane to arrive from Ramstein Air Base in Germany. It touched down at around 9 PM on Saturday, December 15.

The special security detail assigned to the mission unloaded the cargo – a plain aluminum box – from the aircraft. A man and a woman from the US Embassy entered the gatehouse. They had papers they wanted Muhammed to sign, but they were written in English and Muhammed doesn’t speak the language.

Muhammed requested that an interpreter who accompanied him to the air base translate the documents, but the embassy officials rebuffed him, so he declined to sign the paperwork.

The aluminum box was loaded into an ambulance destined for the police hospital. Muhammed, his family and the interpreter followed the vehicle.

Nearly 11 years to the day after he was sold into a “piece of hell”- the US military base at Guantanamo Bay – for a $5,000 bounty, Adnan Farhan Abdul Latif was finally home. The mystery of how he died alone in his cell remains locked in the files of Gitmo. The confusing and often conflicting details have trickled out since his family was advised of his death in September. First it appeared to be suicide, then it wasn’t suicide, then suicide again, then “acute pneumonia” played a role.

A statement issued by United States Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) December 15, the day Latif’s remains were repatriated, however, was definite about the manner of his death.

“The medical examiner concluded that the death was a suicide. Mr. Latif died of a self-induced overdose of prescription medication,” the statement said.

Now an inquiry by United States Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) has also found that some of the prison’s standard operating procedures were not being followed and the failures played a role in facilitating Adnan’s death.

Adnan never belonged at Guantanamo. Two administrations determined as much over a long and tortuous decade. But neurological damage he suffered in a 1994 car accident put him in the wrong place at the worst possible time.

Muhammed wasn’t sure if he and his family would ever get the opportunity to bury and properly mourn Adnan, who left their village near the city of Taiz in the summer of 2001 in search of medical care that was largely unavailable in Yemen.

On December 13, a representative of the Yemeni human rights organization HOOD passed a message from Yemen’s Ministry of Human Rights to Adnan’s family which said that his remains would be returned in two days.

So Muhammed and other member of his family of drove five hours to Sana’a to the Ministry of Justice to meet with the chief prosecutor to obtain permission to go to the hospital to see their brother’s body.

Before they traveled to Al-Dailami Air Base, they stopped over at the home of Minister of the Interior Abdul Qader Qahtan to demand a copy of Adnan’s autopsy report. The minister, reading from what Muhammed believes was a ten-page translation of the document, said Adnan died “from an overdose of medication he had smuggled into his cell.”

“We would like a copy of this,” Muhammed told the minister.

“Soon,” he replied.

At the hospital, Muhammed was led into a room by police investigators and a medical examiner to identify Adnan’s remains. The box was opened. Adnan was wrapped in three layers of shroud.

“I recognized the body of my brother,” Muhammed told Truthout, speaking through an interpreter. “But with great difficulty. His eyes were missing and his body was in an advanced stage of disintegration. Still, I could tell it was Adnan.”

Muhammed requested the medical examiner perform another autopsy on his brother. The medical examiner agreed. Muhammed and his brothers waited in another room. An hour or so later, the medical examiner returned.

“He was very upset,” Muhammed said. “He told me he could not perform another autopsy because his organs were removed and the body was in bad shape.”

Adnan’s body was held for three months at Ramstein Air Base. Todd Breasseale, a Pentagon spokesman, told Truthout the “entirety” of Adnan’s remains were returned to Yemen “for disposition.”

“The condition of Mr. Latif’s body is not at all dissimilar from the condition of any number of post-mortem autopsies, especially given how long ago the autopsy took place,” Breasseale said. “The US returned his remains complete, though to be sure, after months of our adherence to the customs and practices of his religious faith and culture (he was not embalmed), the condition of the body presents in such a way as to make yet another autopsy difficult. While it is standard practice for small, if not trace samples of tissue and organs to be retained by the medical examiner, no complete organs remain in US possession.”

Truthout spoke with the Yemeni medical examiner, Dr. Mokhtar Ahmed Alhrani, through an interpreter. He said he was unable to perform a second autopsy “because of the urgency shown by the relatives of the deceased for the burial of the body.”

“Therefore, we were unable to repeat the autopsy or take sample for pathological and poison examination,” Alhrani said.

He would not respond to questions about whether he told Muhammed that Adnan’s organs had been removed. He said he is still trying to gain access to Latif’s autopsy report, “which we were able to skim parts of in a hurried manner” and is also preparing his own medical report that he will submit to “the concerned authorities in Yemen.”

At around 2:30 AM on the morning of December 16, Muhammed and his brothers left Sana’a and drove back to Taiz.

Although Muhammed had previously told Truthout that he would not accept his brother’s remains without first receiving a complete copy of his autopsy report, he changed his mind after seeing his brother lying in a box.

“I could not leave him,” Muhammed said.

Adnan’s remains were brought into the Shawlak mosque in Taiz just before noon prayer. Hundreds of people were in attendance for what turned out to be his funeral.

Adnan’s 14-year-old son, Ezzi Deen, who had not seen his father since he was a toddler, looked down at his father’s remains and wept loudly.

“You told me in your last letter, you’re coming to me and you will never leave me again, father,” Ezzi Deen said, according to Yemen journalist Nasser Arrabyee, who attended the funeral and reported on the procession.

Adnan’s mother did not attend the funeral. Muhammed told her the condition of her son’s remains would destroy her. Since his burial, she has been bedridden and refuses to speak with anyone, Muhammed said.

Arrabyee reported that Adnan’s father, Farhan Abdul Latif, told villagers who attended the funeral, “We are patient, and we are waiting for Allah’s justice and punishments for America’s crimes.”

Arrabyee reported that a caravan of mourners took Latif’s remains from the mosque to be buried at a cemetery for martyrs.

Lingering Questions

Back in the US, meanwhile, questions about Latif’s death go unanswered.

At first, the military medical examiner who conducted the autopsy on Latif believed the Guantanamo prisoner’s sudden death was the result of “acute pneumonia.”

Joint Task Force-Guantanamo (JTF-GTMO) and SOUTHCOM officials reacted with surprise upon learning that that the high-profile prisoner, who was found face down on the floor of his cell on the afternoon of September 8, had developed the respiratory condition.

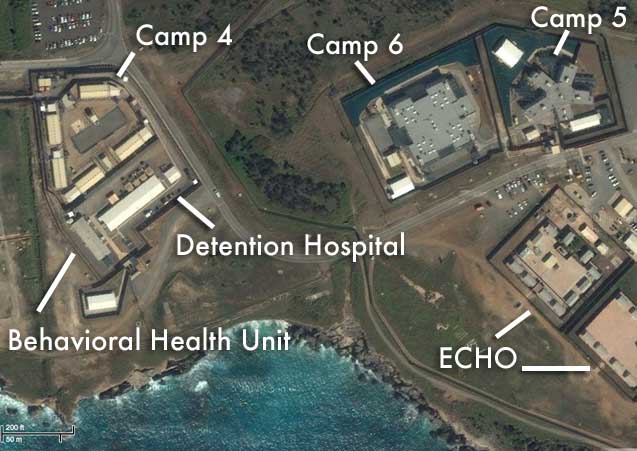

After all, Latif was medically cleared for transfer from the detention hospital where he was housed with hunger strikers to a punishment wing in Camp 5, a maximum security section of the prison, for allegedly throwing a “cocktail” of a mixture of bodily fluids at a guard a day or two prior to his death, according to unclassified notes Latif’s attorney provided to Truthout.

Locations where Latif was held prior to his death in September.

Locations where Latif was held prior to his death in September.

Apparently, no one at Guantanamo was aware that Latif was suffering from acute pneumonia, one miltary official told Truthout.

Dr. Steven M. Simons, a pulmonary disease specialist in private practice in Beverly Hills, California, who was formerly chief of staff at Cedars-Sinai Health System and is also a clinical professor of medicine at the UCLA School of Medicine, said that in his experience, the majority of cases of pneumonia discovered at autopsy in patients who die of drug overdose are caused by aspiration.

“Aspiration means that material either from the mouth or stomach gets down into the lungs because the person has lost the ability to protect their airway, usually owing to a depressed level of consciousness secondary to the drug,” Simons said.

As a frequent hunger striker who was routinely force-fed with the nutritional supplement Ensure, Latif was at risk of developing pneumonia due to the practice of force-feeding. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) noted in an April 2009 letter to then Secretary of Defense Robert Gates that the “debilitating risks of force-feeding include major infections, pneumonia and collapsed lungs.”

It is unknown whether Latif, although housed with hunger strikers at the prison’s detention hospital prior to his death, was on hunger strike at the time immediately leading up to his death, and if so, whether he was force-fed. JTF-GTMO spokespeople would not comment on the matter.

About two weeks after the completion of the autopsy report, the medical examiner concluded Latif’s death wasn’t the result of acute pneumonia, but that the pneumonia was instead a “contributing factor” to his death.

The toxicology test results the medical examiner received showed massive quantities of psychotropic medication Latif had been prescribed in his bloodstream, according to US officials who were briefed about the autopsy report, which remains under wraps. These officials requested anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss the matter.

The only logical conclusion, according to the medical examiner, was that Latif committed suicide. But Capt. Robert Durand, a JTF-GTMO spokesman, told Truthout in October 2012 that although Latif “had a history of self-harm acts,” he “generally refrained from activities which would potentially cause his death” and “his recent actions, activities and statements to therapists indicated that he did not appear to want to end his life.”

SOPs Not Followed

Working from the autopsy report’s conclusion that Latif died of a drug overdose, investigators with the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) and a SOUTHCOM Commander’s inquiry referred to as an AR 15-6 started to probe how he was able to accumulate so much medication and successfully avoid detection by surveillance cameras and by guards who check on prisoners, at minimum, every three minutes and search prisoners’ cells for contraband several times a day; additionally, corpsmen who administer medication are supposed to ensure prisoners have swallowed it by checking their mouths.

“Detainees are supposed to go into a little cage, an enclosure. Once they are in there they are provided their medication and once they take the medicine they are let out. They can’t leave the enclosure until they take it,” one US military official told Truthout, describing the medication administration procedures.

The SOUTHCOM inquiry into Latif’s death determined that some of the prison’s long-standing standard operating procedures (SOPs) were not being followed nor were they enforced, according to US officials who were briefed about the commander’s inquiry.

Several military officials who were familiar with guards’ written reports on Latif’s behavior told Truthout Latif was considered a “belligerent” prisoner who only appeared to “calm down” when he was given his medication. But whoever was responsible for passing Latif his medication never checked to ensure he took it, US officials briefed about the commander’s inquiry said.

In an investigative story published last month, Truthout reported that a total breakdown of the SOPs would have been the only way Latif would have succeeding in hoarding and concealing medication.

Deviating from the SOP is considered to be an Article 92 violation – failure to obey an order or regulation – under the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ). US officials said they did not know if any JTF-GTMO personnel have been reprimanded for allegedly failing to follow the SOPs.

SOUTHCOM will make public the findings of its inquiry, possibly as early as next week.

Even if the SOPs were not followed, as the commander’s inquiry found, where would Latif keep a lethal dose of medication given that in the month leading up to his death he was moved to different cells and camps and searched for contraband?

According to accounts provided to Latif’s attorney, David Remes, by other prisoners, in the month leading up to his death, Latif was shuttled from Camp 6 to the camp psych ward, then to the camp hospital and finally to the disciplinary wing of Camp 5, where he was held in solitary confinement.

When prisoners are moved from their cells, their wrists and ankles are shackled. Remes’ notes state that when Latif was moved from Camp 6 to the psych ward for an incident that took place in a recreation yard in August 2012, during Ramadan, he was not permitted to take any items from his cell with him.

US officials briefed about a separate, NCIS investigation into Latif’s death said several theories investigators have floated include whether Latif hid his pills on his body, inside his cell and/or in his Koran. The officials pointed to an incident that took place in mid-May 2006 in which Adm. Harry Harris, the Guantanamo commander at the time, ordered a “shakedown” of prisoners’ cells following five suicide attempts. The inspections allegedly turned up large quantities of medications, some of which were discovered in a toilet, in a prisoner’s prosthetic leg and “hidden in the bindings of the Holy Quran.”

“Other detainees had apparently saved and transferred their prescribed drugs to designated suicide victims in support of a martyrdom operation,” according to an article written in the May 26, 2006, edition of The Wire, a weekly newsletter published by JTF-GTMO.

The inspections of the Korans by non-Muslim Guantanamo guards, who were accused of desecrating the holy books, led to a riot and then a hunger strike. According to Capt. Alvin Phillips, a JTF-GTMO spokesman, the May 2006 incident “resulted in the SOP that no uniform personnel are allowed to handle the Koran.”

“In the event of a need for the Koran to be searched all linguists can do so,” Phillips told Truthout. Linguists “are all civilian, not military, and it removes the potential for allegations of Koran abuse by the guard force,” he said.

It is unknown whether Latif had a Koran in his cell at the time of his death. Neither Phillips nor Durand would respond to questions about it. A 2009 Pentagon report that reviewed the conditions at Guantanamo said all prisoners, “regardless of disciplinary status,” are given a Koran.

SOP Failures Not an Isolated Incident

SOUTHCOM will also release two other commander’s inquiry reports about two other deaths at Guantanamo which occurred in February and May of 2011. One of those deaths was reportedly a suicide. The commander’s inquiry determined that SOPs were also not adhered to in the case of the prisoner who assertedly committed suicide in May 2011, Hajji Nassim, an Afghan known simply as Inayatullah at Guantanamo, according to the commander’s inquiry.

Nassim, according to statements released at the time by military officials, was somehow able to take a bedsheet into a prison recreation yard and hang himself. Like Latif, Nassim had a history of psychological problems and spent time in the prison’s psych ward. Details surrounding his death have been shrouded in secrecy for nearly two years.

The other prisoner whose death is addressed in a commander’s inquiry, Awal Gul, apparently died from a heart attack after working out on an elliptical machine.

Navy Lt. Cmdr. Ron Flanders, a spokesman for SOUTHCOM, would not comment on the substance of the reports. He said SOUTHCOM filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request with itself last year to have the two earlier commander’s inquiry reports declassified and released. Those reports have been going through a declassification review since then.

“We initiated a FOIA ourselves so it would go through appropriate redaction process,” Flanders said.”

The inquiry into Latif’s death was completed in mid-November, Flanders said, and has been put on a fast track for declassification review and release.

Suspicions Raised About Military’s Account

Breasseale, the Pentagon spokesman, said he could not comment on whether any specific changes to the prison’s SOPs were made in the wake of Latif’s death.

“The JTF consistently reviews its standard operating procedures and updates them as conditions warrant,” Breasseale said. “Changes are made to address any gaps in the SOPs that can be, or have been, exploited by detainees. We do not generally discuss specific SOPs (or our updates to them) for obvious operational and force protection concerns.”

Remes sees shortcomings in the military’s attempt to construct a suicide narrative around Latif’s death. He pointed out that to Muslims, hiding something in a Koran would be considered an insult to the holy book.

“SOUTHCOM has to explain the presence of a lethal amount of medication in the locked cell of the most closely watched detainee in the camp,” said Remes.

“Given the number and frequency of the searches Adnan was put through, the thoroughness of the searches, and the continuous monitoring, the smuggling scenario seems impossible,” he said. “It will be fascinating to see how SOUTHCOM puts it all together.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.