Nueva Colombia is a coffee growing hamlet straddling the border of a natural protected area within the Sierra Madres of Chiapas. A cloud forest of incredible biodiversity, the area is the one of the few remaining homes of the Quetzal bird, revered by the Aztecs and Mayans alike. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)

Nueva Colombia is a coffee growing hamlet straddling the border of a natural protected area within the Sierra Madres of Chiapas. A cloud forest of incredible biodiversity, the area is the one of the few remaining homes of the Quetzal bird, revered by the Aztecs and Mayans alike. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)

Although some market-based strategies to mitigate global warming do benefit some communities, they more often serve as a cheap way for the world’s biggest polluters to avoid true ecological reforms and deprive people who can least afford it of their livelihoods, their land and their homes.

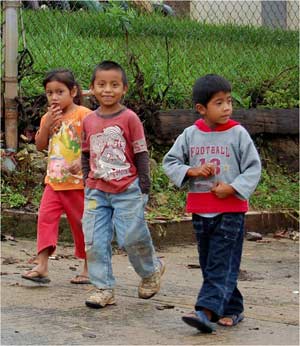

Eleazar Graciliano Lopez Roblero is an inquisitive man with a farmer’s frame, thick, curly hair and staunch hands, who wore a collared shirt and carried a small red notebook with a pen keeping his page. He referred to it a few times, but for the most part he was jotting down notes while the interpreter organized his translations. His wife, a reserved woman with a serious demeanor, sat next to him in the large room that served as their bedroom and living room while his children milled about.

In the courtyard, his sister was preparing a chicken and his niece was cooking tortillas over an open fire. Roblero is the secretary of Nueva Colombia, a tiny village of less than 200 people nestled in the Sierra Madres of Chiapas, Mexico.

‘Coffee is everything’, according to Mr. Roblero. Nueva Colombia had been subsidized by the Mexican government to reforest half their lands. The Mexican government, in return, controversially obtained the rights to the carbon sequestered by the growing trees. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)

‘Coffee is everything’, according to Mr. Roblero. Nueva Colombia had been subsidized by the Mexican government to reforest half their lands. The Mexican government, in return, controversially obtained the rights to the carbon sequestered by the growing trees. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)

Nueva Colombia, a coffee growing hamlet resting on a small plateau on an otherwise steep mountainside, has unwittingly been catapulted to the forefront of the battle against climate change. Roblero’s land, like everyone’s in this village and others nearby, was granted to his family during the land reform program after the Mexican Revolution. Before that, they were landless peasants working for a German landowner. The people of the region produce coffee on the border of a protected natural area called the El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve. A mountainous cloud forest of incredible biodiversity, El Triunfo is known not only as one of the few remaining homes of the Quetzal, a bird revered by the Aztecs and Mayans, but also for its potential to mitigate climate change through carbon sequestration.

The sister of Mr. Roblero, a leading figure in Nueva Colombia. She stated she wanted to move to the SRC because there would be medical facilities and teachers there. That, however, was said before she saw the pictures of the SRC. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)By calculating the amount of carbon captured from the atmosphere and stored in growing forests, carbon credits are generated. One ton of carbon is equal to one carbon credit. Interested companies and institutions can then buy those credits through a carbon market, thereby offsetting their greenhouse gas emissions. The practice, which creates a financial incentive to conserve forests through the marketization of trees’ natural ability to store carbon as biomass, is called Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD).

The sister of Mr. Roblero, a leading figure in Nueva Colombia. She stated she wanted to move to the SRC because there would be medical facilities and teachers there. That, however, was said before she saw the pictures of the SRC. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)By calculating the amount of carbon captured from the atmosphere and stored in growing forests, carbon credits are generated. One ton of carbon is equal to one carbon credit. Interested companies and institutions can then buy those credits through a carbon market, thereby offsetting their greenhouse gas emissions. The practice, which creates a financial incentive to conserve forests through the marketization of trees’ natural ability to store carbon as biomass, is called Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD).

One of the fastest growing international mechanisms for combating climate change, it is based on the theory that a ton of carbon sequestered by a forest in the Global South is identical in function to a ton prevented from leaving a smokestack in the Global North. However, the logic becomes suspect when one considers the burning of fossil fuels as an injection of greenhouse gases into an otherwise closed system known as the carbon cycle. Although some carbon offset projects do good for local populations, they more often serve as a cheap way for the world’s biggest polluters to avoid true ecological reforms and continue on with business-as-usual.

A Surprising Realization

A REDD project has been in existence in the coffee region buffering the El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve since 2008. Managed by Conservation International and in partnership with Starbuck’s Coffee, the project creates carbon credits by growing trees as a shade cover for the coffee farms dominating the first slopes of the Sierra Madres. Starbuck’s buys the shade-grown coffee, which conforms to their Coffee and Farmer Equity (CAFE) practices, while participating farmers receive a subsidy to make up for the lower yield shade-grown produces. The subsidy comes directly from the Mexican government which, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, controversially obtains the rights to the generated carbon credits.

Since Hurricane Matthew in September of 2010, the village of Nueva Colombia has been without medical facilities or school teachers. Jaltenango, the only town in the area and over four hours away, is where the mobile hospital unit is now stationed. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)In 2010, seeing other communities benefiting from doing something they already do, Nueva Colombia asked to join the program. Yet, since the farmers of Nueva Colombia already produced shade-grown coffee, they were ineligible for the program. In response, the Mexican government decided on a novel approach – subsidizing the farmers of Nueva Colombia to completely reforest half their lands. Incidentally, all the lands allowed into the contract were lands used to grow corn for personal consumption.

Since Hurricane Matthew in September of 2010, the village of Nueva Colombia has been without medical facilities or school teachers. Jaltenango, the only town in the area and over four hours away, is where the mobile hospital unit is now stationed. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)In 2010, seeing other communities benefiting from doing something they already do, Nueva Colombia asked to join the program. Yet, since the farmers of Nueva Colombia already produced shade-grown coffee, they were ineligible for the program. In response, the Mexican government decided on a novel approach – subsidizing the farmers of Nueva Colombia to completely reforest half their lands. Incidentally, all the lands allowed into the contract were lands used to grow corn for personal consumption.

For two years, the people of Nueva Colombia received this subsidy and laid fallow the lands agreed upon. Then, in July of 2012, they were visited by officials of the Mexican forestry agency. They were informed that they’d no longer receive the payments for reforesting their lands, and worse, that they still couldn’t plant on them either. Doing so would be illegal, they were told, since the lands are now a part of the El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve.

In August of 2012, we visited Nueva Colombia and talked with Roblero. He thought we were there for another reason, but after some prodding and bringing the subject back to reforestation, he told us of how his lands were seized by his government. Surprisingly, he expressed confusion as to why he and his fellow farmers were being subsidized to reforest in the first place. He had never heard of REDD or the carbon market, nor the ways in which carbon credits were generated and what they were used for. We apparently were the first to do what is supposed to be done under REDD protocol and international law – tell participants about what a REDD project does, and why. He couldn’t believe it, and as the discussion turned serious and his disposition indignant, he told his children to go to the courtyard.

Sustainable Rural Cities

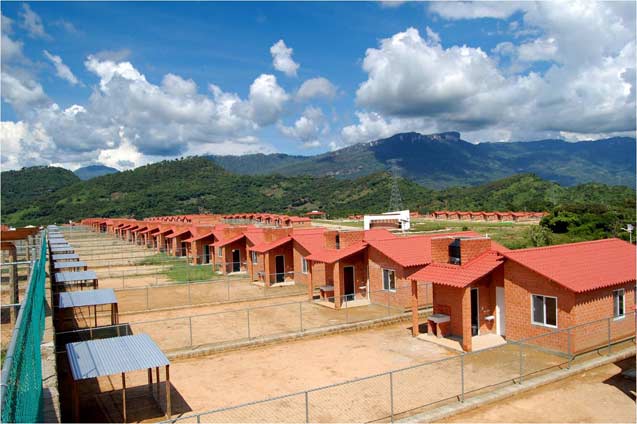

Roblero thought we were there to discuss a housing development that is under construction in Jaltenango, the only town in the region, at the eastern base of the Sierra Madres of Chiapas. It is more than four hours from Nueva Colombia. At 197 acres and with 625 identical houses, the development will nearly double the size of Jaltenango. It is one of five Sustainable Rural Cities (SRC) built – or in the process of being built – in Chiapas.

A living unit within the makeshift tent city, located in Jaltenango. After Hurricane Matthew in 2010, the Mexican government convinced some families to give up their land in exchange for a free title to a house. They’ve been living here since, waiting for the SRC to be completed. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)

A living unit within the makeshift tent city, located in Jaltenango. After Hurricane Matthew in 2010, the Mexican government convinced some families to give up their land in exchange for a free title to a house. They’ve been living here since, waiting for the SRC to be completed. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)

All the families in Nueva Colombia and people from nearby hamlets are slated to move to the SRC when it is completed by the spring of 2013. The Mexican government has offered them a title to a house for free, and at the same time, has been dispatching officials to the various communities to inform them of the natural hazards of where they are living. A construction worker at the SRC site stated he was told his community was in danger of plummeting to their deaths when the ground they live upon breaks from the rest of a mountain, and that Nueva Colombia is in danger of a catastrophic flood.

In fact, in September of 2010, Nueva Colombia did flood and was affected by serious mudslides. Since then, the community has used the money from the reforestation subsidy to pave roads and create a drainage system.

But from that incident, the Mexican government convinced many families to give up their land in exchange for the free title to the house. They’ve been living in a makeshift tent city in Jaltenango ever since, waiting for the SRC – which they were told back then would be ready in six months – to be completed.

In addition, many people left Nueva Colombia after the flood when the Mexican government did not allow the teachers or the mobile hospital unit to return to the village, Roblero said. The community has been without medical services and a functioning school for two years now. It was obvious to him that his government has wanted residents out of the area, but it wasn’t until we explained the carbon market that he put all the pieces together.

The Roblero family said they were not willing to move to the Sustainable Rural City, and became more resolute in their decision once we showed them pictures of the development. Cornell University conducted an analysis of the program, citing countless faults. In every house in the Jaltenango SRC, for example, were two children’s rooms, each barely larger than the small bunk beds inside, with a thin, shoddily built wall that did not go to the ceiling between them. The roofs were made of aluminum and, unlike traditional house-building practices in the area, there was no space between the roof and the tops of the wall to let out the hot, humid air.

The courtyard of the Roblero family. House-design practices dictate an opening between the top of a wall and the roof. This lets out the hot, humid air. Compare this to the aluminum roofs and ceramic walls which seal in the houses of the SRC. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)

The courtyard of the Roblero family. House-design practices dictate an opening between the top of a wall and the roof. This lets out the hot, humid air. Compare this to the aluminum roofs and ceramic walls which seal in the houses of the SRC. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)

The women of the family were especially taken aback by the massive power lines that divided the SRC, and the buzzing sound they emitted, which could be heard from any corner of the development. Truthout interviewed an engineer of the housing development. He stated that it was the UN that decided on the housing plans and the materials used, and that it is in line with the UN Millennium Goals.

Roblero can’t help but see a connection between the Sustainable Rural City and the Mexican government’s desire to generate as many carbon credits as possible. All the communities slated for relocation are at least partially within the boundaries of the El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve, which was created in 1990.

He was never afraid of the warnings of the officials who come every so often to warn of the natural dangers of the area, stating there are many communities all over the world in a worse position than they are in. But Roblero said he and his family will not leave their land, even if their government tries to use violence to relocate them.

Canary in the Smokestack

The Mexican government is receiving funding from The World Bank, the UN and other multilateral institutions to create a national REDD program. The objective is to evaluate the effectiveness of national-scale REDD programs on efforts to conserve ecologically intact forests of the Global South.

However, trees as a canopy for coffee farms or plantations of palm trees for biofuels – both of which are currently generating carbon credits in Mexico – hardly resemble a forest. Currently, all REDD contracts in Mexico are for five years. On average, however, individual REDD projects have a contract length of 30 years. What happens then? Truthout interviewed Jose Carlos Fernandes Ugalde, the financial director of Mexico’s national REDD program. He refused to respond to several questions, including this one: What happens when the farmer, whose livelihood depends on the reforestation subsidy, no longer receives that subsidy, and the area reforested during the contract no longer has an economic value?

One section of the SRC. Every front and back yard will contain an orange tree, the fruits of which will supposedly benefit the community through their export. Note the irony of clear cutting this area in order to generate carbon credits through reforestation in another area. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)

One section of the SRC. Every front and back yard will contain an orange tree, the fruits of which will supposedly benefit the community through their export. Note the irony of clear cutting this area in order to generate carbon credits through reforestation in another area. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)

Mexico plans to shovel the credits it is generating now into the carbon markets in June of 2013. The country sees itself as a future leader in the nascent green economy by becoming a top supplier of carbon credits for the Global North. At an average of $6.20, quite a few credits will have to be generated to make it economically worthwhile.

As part of this strategy, California, whose cap-and-trade system for reducing emissions statewide goes into effect in January of 2013, is building the legal framework to eventually buy carbon credits specifically from Chiapas. The first of its kind, this deal will solidify into REDD practice the human rights abuses inflicted upon the people of Nueva Colombia, including the possible forced evictions once the otherworldly housing development is complete. Thus far, this is the only international source for carbon credits California is considering using as an acceptable way for its companies and institutions to offset their emissions. If accepted, it would be upon the backs of the farmers of Nueva Colombia that California, one of the world’s worst polluters, is dumping its responsibility to mitigate climate change onto.

The two children’s rooms within any given house in the SRC. Not yet fully furnished, a tiny desk and bureau is still to be placed in each. The dividing wall reaches only a foot or two higher than the top bunk, leaving a large space within the gabled roof. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)

The two children’s rooms within any given house in the SRC. Not yet fully furnished, a tiny desk and bureau is still to be placed in each. The dividing wall reaches only a foot or two higher than the top bunk, leaving a large space within the gabled roof. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)

As stated in the Framework Document of the United Nations REDD Program, REDD projects have the potential to “lock up forests by decoupling conservation from development.” It also states that “asymmetric power distribution [could] enable powerful REDD consortia to deprive communities of their legitimate land development aspirations.”

Truthout interviewed Tamra Gilbertson, one of the founders of Carbon Trade Watch, which provides research on environmental policies and climate justice with a special focus on carbon trading, forest issues and land rights.

Gilbertson said her research has confirmed the reservations expressed in the UN-REDD Framework Document. She had this to say: “As REDD develops into large government programs in the Global South, the negative impacts on local communities seen in individual projects to date will become institutionalized in both governmental policy and through REDD protocol. The lack of accountability then becomes entrenched within a framework that violates human and indigenous rights for the sake of so-called ‘sustainable development.'” This is the way REDD will work as it, and the cap-and-trade systems and national programs it is merging into, continue to grow in popularity.

We should consider this the canary in the smokestack.

The sun had risen and eventually dried up the clouds rolling through the valley. On a walk to the coffee farms, amidst impassioned discussions of all that could be and has been stolen from these resolute people, beauty was still to be found. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)

The sun had risen and eventually dried up the clouds rolling through the valley. On a walk to the coffee farms, amidst impassioned discussions of all that could be and has been stolen from these resolute people, beauty was still to be found. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)

The immediate Roblero family. Like the rest of the community, they didn’t understand why they were being subsidized to lay fallow half their lands. Against REDD protocol, they were never informed about the carbon market or the concept of carbon rights. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)

The immediate Roblero family. Like the rest of the community, they didn’t understand why they were being subsidized to lay fallow half their lands. Against REDD protocol, they were never informed about the carbon market or the concept of carbon rights. (Photo: Jennifer Coute-Marotta)

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.