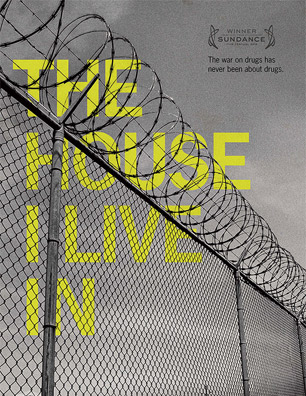

How do you make a film about a subject as expansive and many-tentacled as the drug war? Do you focus on its circuitous history? The injustices of sentencing? The destructive effects on families and communities? The profit motives that fuel the system? The impact on policing, law enforcement and public safety? The ways in which entrenched racism and classism dictate the system’s targets? The answer for filmmaker Eugene Jarecki was a whopping “all of the above.” In the stunning “The House I Live In,” he depicts the vast sweep of this insidious campaign’s effects, while portraying the nuanced – often conflicted – views of the political and economic players who perpetuate it. The film delivers a multi-dimensional picture of an issue of which we’re usually able to view only slices, demonstrating, in sum, the colossal failure of the 40-year “war on drugs.” I got on the phone with Jarecki to discuss the film, and how he is using it as a tool to spark tangible action.

Maya Schenwar: “The House I Live In” covers such a massive and complex topic, and you captured that complexity while showing that there is a very clear verdict as to whether or not the war on drugs has worked. In addition to interviewing progressive activists and incarcerated people, you interviewed police, prison guards, judges – all those folks – and you didn’t hear the things we might expect to hear from them. So, I’m wondering, how did you decide who to interview, and what was that process of decision-making like?

Eugene Jarecki: I wanted to portray the fullness of the issue. As the drug war has grown over time, it’s like any predatory monster; it knows no bounds. I was convinced from early on we needed to travel far and wide and talk to people at all levels of the drug war, from the dealer and the user to family members to community members to cops, jailers, judges, lawyers, wardens and then – ultimately – to policymakers.

I wanted to see how people inside the system felt, far more than I wanted to hear from critics. There are critical voices in the film, people like David Simon and Richard Miller and Charles Ogletree and Michelle Alexander – very smart critics who put what the viewer sees in the larger political and historical context – but what mattered most to us was the firsthand experience and testimony of the people whose stories are wrapped up in this issue.

People surprised us greatly. You go into the prison system and you think, well, the people who run Corrections, they’ll be the real “tough on crime” people, and they’ll explain to me how they see the world, which will stand in great opposition to the way a drug dealer I just spoke to sees the world. But we found out how many people on the inside, up and down the chain of command, viewed the system deeply critically. That was unexpected, and that became the most inspiring part of making the film.

Almost no one believes in this system. In looking for diversity – crossing the country and encountering so many different walks of life and so many geographies – I ended up finding an extraordinary unanimity: the idea that the drug war has been with us for 40 years, we’ve spent a trillion dollars on it, we’ve had 45 million drug arrests, and we have nothing to show for it. So, it was almost impossible to find someone who would defend a record like that.

MS: Wow. Did you meet anyone who did wholeheartedly defend it?

EJ: No. The only people who come close to wholehearted defense – and it’s halfhearted defense in their case, honestly – are the people on the profiteering side of the war on drugs, whose livelihood depends on it. So, as in so many professions that have a dark subtext, they’ve developed a sort of Orwellian doubletalk, to euphemize and obfuscate about what they do. They have all kinds of prepared argumentation about the benefits of the way in which they profit from it, the services they provide. Their phone services are better, or they sell a better stun gun than the other stun gun, or their restraint chair is better than the old kind of restraint chair that another company made. At the micro level, they may all have something to say about how they’re making a better good or service at a better value, but it is within what even they would recognize is not the best way to make a living – it’s probably not the career they dreamed of when they were in high school.

Do you support Truthout’s reporting and analysis? Click here to help us continue doing this work!

Now certainly, all across the country, you’ll find that there are people who believe that the legal system should be uncompromising when it comes to the violent and the super-violent. But we’re talking about incarceration on a mass scale of the nonviolent – people who do not pose a threat to you or me; they pose a threat mostly to themselves. Who would defend sentences for the nonviolent that are often longer than sentences for the violent? That anomaly in the American legal system doesn’t have a lot of advocates – certainly not the judges who, half the time, are forced to give sentences they feel are inappropriate. The mandatory minimum laws that set minimum penalties [for drug offenses and certain other crimes] are so far-reaching in America that the judges find their options incredibly limited. One judge said to me, “The kid standing before me on a crack cocaine charge with a previous offense, also nonviolent, is facing 20-year mandatory minimum for five grams. If he had won the medal of honor or pulled his grandmother out of a burning building yesterday, I couldn’t take that into account in his sentencing.”

Across the country, we found this almost unanimous chorus of voices agreeing that this system doesn’t make any sense. It is a victim of the same corruption of politics that’s ruining so many walks of life in America: corporate America and Congress are in an unholy alliance with each other, in which Congress members ensure their electability by servicing their corporate patrons, who then bring jobs to their districts and money to their campaign coffers. That unholy alliance is behind the military industrial complex, it’s behind the pharmaceutical industry, it’s why we have the insurance corruption we have, it’s behind the banks, it’s why the polluters get away with murder. The prison-industrial complex is just, perhaps, the most obscene example of that phenomenon that has taken over every walk of American life.

MS: So, even if we believe that these policies need to change, and even if the majority of the country believes it – if corporate interests are calling the shots, it seems so tough to cut through those profit motives. From your experience working on the film, can you describe the possibilities you see for breaking out of that cycle of profit-driven mass incarceration?

EJ: Revolutions happen in societies. They even happen when there are industries and deeply entrenched interests that have come to rely on the status quo. Believe me, there were vast economic dependencies built into slavery. I believe that, ultimately, the reason the prison industrial complex is vulnerable is that with both its record of failure and its level of expenditure, it’s harder and harder to defend at a time when country is so economically challenged. At a time like this, a gigantic, wasteful program like our system of mass incarceration is suddenly susceptible to attack not only from those who think it’s morally bankrupting, but also those who see it is economically bankrupting. This isn’t an actual business that makes a product that you can sell to somebody, or that other countries can buy. You can’t sell the misery of a prisoner. You can’t sell his destroyed family, his orphaned children, his shattered community.

In fact, this “product” weakens us in the world because it erodes America’s workforce. Imagine all the people wasting away in jail right now who are simply drug-addicted people… How many of our famous geniuses were [drug users], from Thomas Edison to Steve Jobs? Who knows who’s wasting away in a prison cell right now that could have made the next big thing that would help America’s economy? There’s nothing productive about digging a giant hole in the ground and throwing your own people and your own money into it.

This system also represents an overexpansion of government and a giant bureaucracy, so that those like Grover Norquist and Pat Robertson who are against the drug war can find common ground with people like Danny Glover and Cornel West, who see the drug war as ethically, socially and spiritually destructive to America. How our beacon of democracy can reconcile that identity with having become the world’s largest jailor – it’s very difficult for a wide range of people to get their heads around it.

MS: So, it seems like there are some great alliances emerging in the activist community around the drug war and mass incarceration. But regardless of the kinds of grassroots work being done, incarceration and the drug war don’t make nice campaign issues, because lawmakers “have” to talk about being tough on crime. For us, as people who want to make a difference, what can we do to put pressure on our elected officials and bring these issues to their attention?

EJ: Well, I recommend several things people can do. With the film, we are trying to shed light on how important it is that people going forward hear the phrase “drug war” as a dirty word, like slavery, or Jim Crow. First and foremost, the movie is meant to show the wrongheadedness of this 40-year campaign, whose failure demonstrates its misconception of the problem. So I want to make sure there’s a very clear recognition in the public space that those days of buying into that logic are over. For everyday people, that means they have to internalize that idea, and become walking messengers of it – to their friends, over email, through any organizations they belong to. That also means that when a politician comes before us and uses the kind of “tough on crime” rhetoric that politicians used to use to work the public into a frenzy and get them to support draconian sentencing and law enforcement, we must boo and hiss them. It should be like someone standing there giving you all the reasons why you should support slavery – you would boo and hiss them until they were replaced with someone who spoke like we do in the modern world.

Instead, we need to be talking about smart on crime legislation, which means treatment, and careful and judicious use of the law – frankly, far more like what Richard Nixon did. Even though Nixon launched the war on drugs, as a policymaker, he had a very interesting balance: he spent the majority of his drug budget on treatment and the minority on law enforcement. We do the reverse.

We also want to look at other examples in the world. Portugal has decriminalized possession across the board. They maintain the power to incarcerate those who deal drugs, but have stopped incarcerating those who use them – and the results have been extraordinary, by every leading indicator: social, economic and legal.

So, the goal for the public is to make them aware of the problems with the drug war and shift their voting patterns so they are driven by sanity on this most important issue of social justice in American life.

At the local level of effecting change, the public has a different role. At our website, you have the opportunity to enter your zip code and find out who’s working to fight against the drug war in your area, and how you might fit into the effort to change this horrible situation…. State by state across the country, there are policies – like “three strikes” in Californiai and stop-and-frisk in New York – that must be the focus of anyone concerned with the war on drugs, so that the deep local underpinnings of the system begin to be shaken, while we sink into the reform level more broadly at the top.

MS: In terms of policy change: the film points toward ending mandatory minimums, and other reforms that would substantially decrease the incarceration of drug offenders. But I start thinking about all the people – including some of the people interviewed in the film – who commit crimes that aren’t explicitly drug crimes (like trafficking or possession), but they’re still crimes that are committed in order to obtain drugs: robbery, or burglary, or sometimes even violent crimes. These crimes are happening because these people are caught up in the system, and often, because they’re addicted to drugs. But since those crimes are not explicitly drug crimes, would they also be confronted differently in the new system you’re pointing toward?

EJ: Well, in a world where you emphasize treatment in society, you wouldn’t let go of the fact that we have, appropriately, very tough laws for violent crimes like rape and murder. But in our current system, by having a blurry approach to drug addiction in which you treat addiction like a violent crime, we’re actually creating more criminals and increasing violence. We take a nonviolent person who’s simply struggling with their own addiction, and incarcerate them, and in prison, they learn to become more advanced criminals; we concentrate that person’s education in more violent criminality, in a confined space where there are few other role models. They then come out with a strike on their record, making it nearly impossible for them to get a job, therefore increasing the likelihood that they will get involved in the underground economy and use their newly learned violent tactics.

Likewise, when we empower and incentivize police to rack up untold numbers of petty drug arrests, rather than focusing their energy on more serious crimes, we compromise public safety as well, because now we have police on the street filling quotas and earning overtime by involving themselves with nonviolent petty drug arrests; more serious crimes go on around them with insufficient pursuit.

If drugs were not criminalized in the way that they are, if they were controlled as substances and people were given treatment, you would have far less violence associated with addiction, because people would be dealing with far less addiction. By leaving addiction untreated, we leave it there to foster violence and criminality.

MS: Going back to the way in which you’re hoping the film will lead to a shift in public opinion: it has always frustrated me that mainstream media tend to veer away from criminal justice in this way – they often bypass the injustices of the system and focus on “crime” in a vacuum. Can you talk about the ways in which you’re using the film as a tool to build awareness and advocacy?

EJ: What we’re doing with the film is very much educated by what I’ve learned over the years through making other films. I learned with those films that although they enjoyed the life of high-profile documentaries, that was a limited life, because documentaries in America are distributed with some prejudices about who the movie-going public is. It was clear to us that some of the key audiences to whom the film would matter the most – a lot of them live in places, whether in the inner city or in the heartland of this country, that don’t typically have art houses that show serious documentaries. So we knew from early on we would pursue screenings in schools, churches, prisons and other public institutions.

Some of the most exciting screenings we’ve had have been in prisons: we were given remarkable access to show the film in several prisons in Oklahoma. The prisoners were made very angry by the film in one way, because it explains a lot about the unfairnesses that have befallen them, but at the same time they felt loved – by those of us that made the film, and even by the Department of Corrections of Oklahoma, that was willing to respect them enough to show them the film and bring them into this conversation. Those screenings in prisons have been deeply inspiring. I’m also speaking in churches and schools in Chicago, Los Angeles, New York and across the country.

The goal is to bring an ever-growing cross-section of Americans into this extremely important and sensitive conversation, and build an ever-growing constituency that recognizes that we need a change here. This includes people who work in the prison system and are worried about losing their jobs. In a treatment-based system there are a ton of jobs: it’s a huge thing to be able to deal with the most massive addiction problem of any country on earth. Many of these [prison employees] have worked for decades to try to help people steer clear of their addiction; they’ve just done it in incarceration settings.

I want to see us focus on treatment in a real way, where all these people could shift into jobs in which they’re proud of what they do. There’s nothing scary about this. We once went from buggy whips to automobiles – and yes, it was a change, and there were growing pains, but I don’t think anyone wishes we’d go back to buggy whips.

We have new information about the drug war now. Decades have told us that this is not the way to do it! So we’ve got to regroup and find an inspired way of becoming the envy of the world instead of the laughingstock – or rather, the cryingstock – of the world.

MS: I love that idea of not only taking the film to various communities, but also taking it inside, and hopefully sparking productive conversations among people who are directly affected. Imprisoned people are such an important part of this discussion.

EJ: I’ve made a rule with my team: we’re not taking on any new film production until further notice so that we can do best job of getting this film out at the grassroots level. We’re devoting every ounce of energy to getting this film out so we can make some change here. I don’t just want to be a merchant of despair; I don’t want to just sell sad stories for a ticket price and have people buy popcorn and see how terribly we’re treating our fellow human beings. I want to see this system get better!

Thank you for reading Truthout. Before you leave, we must appeal for your support.

Truthout is unlike most news publications; we’re nonprofit, independent, and free of corporate funding. Because of this, we can publish the boldly honest journalism you see from us – stories about and by grassroots activists, reports from the frontlines of social movements, and unapologetic critiques of the systemic forces that shape all of our lives.

Monied interests prevent other publications from confronting the worst injustices in our world. But Truthout remains a haven for transformative journalism in pursuit of justice.

We simply cannot do this without support from our readers. At this time, we’re appealing to add 50 monthly donors in the next 2 days. If you can, please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly gift today.