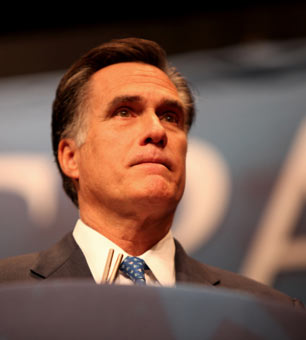

Last week, the website Gawker published more than 900 pages of documents from Bain Capital, the private equity firm Mitt Romney founded, and headed from 1984 until 1999. The document dump didn’t reveal much about Romney’s personal investments, but it added a bit more to the pressure on Romney to release more of his tax returns. Romney and his wife Ann have repeatedly rebuffed such calls. In a primary debate in January, Romney said he’d paid “all the taxes that are legally required and not a dollar more.”

So what do we know about how he avoided that extra dollar? For an overview of the questions surrounding Romney’s tax strategies, see Vanity Fair’s comprehensive story “Where the Money Lives,” and this commentary from tax lawyers Edward Kleinbard and Peter Canellos. We’ve also rounded up the best reporting on the central controversies.

What’s Been Disclosed?

Romney has released his 2010 tax return, and an estimate of his 2011 return. (He filed for an extension this year and has said he’ll release the full returns when they are finished. The deadline is Oct. 15). We also have 2010 returns for blind trusts for Romney, Ann, and their family, and the family foundation, as well as financial disclosures from his campaigns, beginning with his 2002 Massachusetts gubernatorial run.

Mitt Romney said recently that he has paid “at least 13 percent” in federal income taxes each year, but the campaign won’t go into more detail (for a closer look at his 13.9 percent rate in 2010, see our previous reading guide). Ironically, it was Mitt Romney’s father, George, who set the precedent for the kind of comprehensive disclosure that’s standard for most presidential candidates: During his 1967 bid for the Republican nomination, he released 12 years of tax returns, saying that just one or two seen in isolation could be misleading.

Romney’s Bain Career

Buyout Profits Keep Flowing to Romney, New York Times, December 2011

The New York Times laid out how Romney’s generous retirement deal let him keep investing in new Bain funds for 10 years after he left the company in 1999. He got a share of the profits from 22 funds, as Bain’s assets grew 20-fold. (If you’re hazy on how private equity, or leveraged buyout firms, as they used to be commonly known, actually work, see Marketplace’s plain-speak explanation.) Such retirement deals aren’t without their critics among tax professionals. Lee Sheppard of the blog Tax Notes argues that compensation packages should not include capital gains from funds which the individual had nothing to do with.

Romney using ethics exception to limit disclosure of Bain holdings, Washington Post, April 2012

Candidates for federal office are required to disclose financial holdings, but since the 2004 election, the Office of Government Ethics has let candidates postpone reporting underlying assets in accounts that are bound by confidentiality agreements. That applies to most of Romney’s Bain assets. It’s not the first time a presidential candidate has used the confidentiality exception — in fact, in 2004 Democratic nominee Sen. John Kerry didn’t report the underlying assets held in a Bain Capital fund by his wife, Teresa Heinz Kerry. But the size and portion of Romney’s assets that are shielded are unprecedented, according to the Post.

Romney’s Tax Rate

Why Mitt Romney’s Tax Rate is 15 Percent, Planet Money, and Romney as Multimillionaire Gets Break for Taxes, Bloomberg, January 2012

Much of Mitt Romney’s “income” from his private equity career likely isn’t considered income at all, but something called carried interest. Private equity firms (like hedge fund managers) are paid along a “two-and-twenty” model — a fee of two percent of the assets under management, and then 20 percent of whatever profits there are, the “carried interest.” The fee gets taxed as income, at a rate of 35 percent, but the carried interest is treated like investment income, and so it is taxed at the capital gains rate of 15 percent. There’s debate over whether that’s fair. That carried interest is a part of managers’ fee-structure, so some argue it should be considered earned income rather than capital gains. In 2007, members of Congress proposed legislation that would make carried interest be taxed as income. (For more on the debate, see also our previous reading guide).

Romney’s Management Fee Conversions, Victor Fleischer, August 2012

About that two percent in the two-and-twenty model. Colorado University Law School professor Victor Fleischer noted that the Gawker documents show that for several funds in which Romney was invested, Bain had waived the two percent fee, in exchange for another profit share arrangement. According to the Times, the documents show four Bain funds converted $1.05 billion in fees into capital gains. In this model, if there are profits, the fee, which had been taxed as ordinary income, is now converted into carried interest, and taxed at the much lower 15 percent rate.

Fleischer, whose research fueled efforts in Congress to tax carried interest as income, maintains that such conversions are illegal. The risk that Bain takes by waiving the fee, he argues, is immaterial, because the firm is so well-positioned to know which investments will succeed. If fee conversions are indeed illegal, they are nonetheless widespread in the private equity world; Fleischer doesn’t know of any cases in which the agency has challenged them.

Romney has reported investments in some of the funds that waived fees, but since we don’t have specifics, we don’t know for sure if or how he benefitted from the conversions.

Romney’s IRA’s off-shore investments: helping his tax bill? Wall Street Journal, January 2012

While the Gawker documents provide a detailed look at how Bain runs offshore accounts, we’ve known for some time that Romney has considerable assets stashed in them. Romney said Sunday that Bain uses accounts in the Cayman Islands and elsewhere to attract foreign investors, and that he’s gotten “not one dollar reduction in taxes” from the offshore accounts. But as the Journal reported back in January, that claim is misleading. Non-profits and large retirement accounts can be subject to the “unrelated business income tax,” which is meant to keep tax-exempt entities from competing with commercial businesses. If Romney’s IRA was invested in Bain funds in the U.S., it would probably be subject to the tax. By investing in blocker-corporations — offshore partnerships that then make investments for them — IRAs avoid it.

Documents Show Details on Romney Family’s Trusts, New York Times, August 2012

The Times lays out what the Gawker documents show about Bain’s use of an investment strategy known as equity or total-return swaps. It’s a strategy, widely in use, that lets non-U.S. investors avoid a tax on dividends paid by American companies. An offshore fund will enter an agreement with a U.S. bank or brokerage firm, in which the American company “owns” stocks, but transfers all the gains or losses to the offshore fund, in exchange for interest. The swaps are side-bets, mirroring the motions and benefits of owning stocks, but aren’t subject to the dividends tax. Congress passed legislation curbing such swaps, and pending IRS regulations are supposed to put a stop to them, but they aren’t fully in effect yet.

Aside from the IRA account, what’s the motivation for an American individual like Romney to invest overseas? It may just be to have access to investment funds that are held offshore to attract foreigners, as Romney has explained. Still a little murky are entities like the Bermuda-based Sankaty High Yield Asset Investors Ltd., wholly owned by Romney and the subject of scrutiny from Vanity Fair and the Associated Press. Edward Kleinbard, a professor at the University of Southern California’s Gould law school, says there are legitimate reasons Romney might have organized such a corporation to serve a specialized tax purpose, but without full disclosures, “there’s no way to know why he needs to hold Sankaty, personally, overseas.”

Tax Credits Shed Light on Romney, New York Times, August 2012

An in-depth look at how Romney, like many wealthy individuals, has used foreign tax credits to reduce his U.S. tax bill. In 2010, Romney claimed nearly $130,000 in foreign tax credits. Unused credits can be rolled over from year-to-year, making them a handy tool for offsetting gains in particular years. Again, nothing illegal, but another way to apply the complexities of the tax-code so as to minimize his bill.

Boston Lawyer Keeps Steady Hand on Romney’s Holdings, Boston Globe, January 2012

In an interview with the Globe, R. Bradford Malt, the lawyer in charge of Romney’s trust, defends the use of a (now-closed) Swiss bank account. The Swiss account was opened in order to diversify Romney’s investment in foreign currencies, not to hide assets, Malt says. The Swiss account was initially left off the federal financial disclosure Romney filed last year, in what his campaign called an oversight. We don’t know if Romney reported the account in earlier tax returns, or in required reports to the Treasury aimed at preventing money-laundering and other offenses. Non-reporting of Swiss and other accounts was widespread until an IRS crackdown in 2009.

Romney’s Children’s Trust

A Clue Emerges to Romney’s Gift-Tax Mystery, Wall Street Journal, August 2012

The Romneys established a trust for their heirs, which is now worth roughly $100 million. The campaign told the Journal that Ann and Mitt have never paid gift taxes on contributions to the account, because they were under the lifetime maximum — $600,000 each in 1995, then $1 million, until a recent exemption raised it to $5.12 million. Even the couple’s maximum contributions still would have had to grow ten-fold to get to $100 million.

The Journal uncovered a 2008 presentation by Ropes & Gray, a law firm that has advised Bain Capital (and where Malt, Romney’s trustee, is a partner). It reveals one strategy that was apparently common until about 2005: Because carried interest is a share in potential profits, it could be given away at low or even zero value, since those profits theoretically might never materialize. It’s hard to believe that an established private equity firm like Bain could really envision no profits from that carried interest, raising questions about whether those were fair-market valuations of the gifts. A Romney adviser told the Journal that the Ropes & Gray presentation described industry practice, and that one “should not assume” the Romneys took advantage of the strategy. This mystery wouldn’t necessarily be solved if Romney released his tax returns, since gift-tax returns are filed separately.

Romney’s Enormous IRA

Bain Gave Staff Way to Swell IRAs by Investing in Deals, Wall Street Journal, March 2012

Romney has somewhere between $20 million and $102 million in an individual retirement account. Given the limits on contributions to IRAs, that’s an unusually large one: According to the Boston Globe, even an IRA with $20 million would put him in the top .001% of such accounts. One way it might have grown so spectacularly: Bain employees had the opportunity to invest, via their retirement accounts, in the company’s deals. Employees often bought high-risk, low-cost shares for their retirement accounts. During Bain’s boom, they exploded in value, with none of it taxed in the short-term. Were those shares undervalued when they were placed in IRAs? According to the Journal, tax lawyers couldn’t point to an instance where the IRS challenged valuations in private equity retirement accounts. Romney did use his IRA to co-invest in Bain deals, but it’s not apparent whether he used the strategy outlined by the Journal.

Blind Trusts

Mitt Romney’s Blind Trust Not So Blind, ABC News, December 2011

When faced with questions about his investments in offshore accounts or carried interest, the Romney campaign generally points to the fact that since 2003, when Romney became governor of Massachusetts, his assets have been held in a blind trust, over which Romney has no control. But some have questioned whether Romney’s trustee, who is his personal lawyer and longtime associate Malt, is too close to Romney to make the trust truly blind. ABC noted a million-dollar investment in a company founded by Romney’s son, Tagg. The trust would not meet the requirements for federal office, which hold that an institution with no financial ties to the official must control the assets.

Rafalca the Horse

Romneys Have Tax Deduction with Olympic Hopes on Rafalca, Bloomberg, July 2012

Since you’ve made it this far, one more nugget of controversy: On their 2010 returns, the Romneys claimed their Olympian dressage horse was a business, not a hobby. It’s not a profitable business, though; Ann Romney reported a $77,731 loss for the year. For a business, with losses, Ann was able to claim a deduction, Bloomberg says, though only $50 that year. According to Bloomberg, the IRS regularly challenges people who classify their horses as a business.

Glossary

Private equity: Private equity describes investments in companies that do not have publicly traded stock. In what’s known as a leveraged buy-out, private equity firms raise money to buy control of a company and restructure it in hopes of making it successful. The goal is usually to sell it for a profit within a few years.

Capital gains tax: A tax on the profits realized when investors sell an asset for more than they bought it for. In the U.S., capital gains are taxed at 15 percent, lower than “ordinary” or “earned” income, such as wages, salaries, tips and bonuses.

Carried interest: A share of profits that managers of private equity and hedge funds get as compensation. They are taxed at the 15 percent capital gains rate.

Individual retirement account (IRA): A savings account where individuals can stash a limited amount each year, tax-free. Taxes are paid only when money is withdrawn, usually after retirement, and there are penalties for early withdrawals.

Tax credit: An amount of money that can be subtracted from your total tax bill. It’s different from a tax deduction, which is a reduction in your taxable income.

Blind trust: When the beneficiaries of a trust have no control over or knowledge of the investments being made on their behalf.

Blocker corporation: An offshore company through which pension funds, non-profits, or retirement accounts can make investments without incurring something called the unrelated business income tax, which is meant to keep tax-exempt groups from competing with businesses.

Total return swap: A deal in which one party owns stocks, but transfers all the gains or losses to another party in exchange for interest. The second party gets the benefits or losses of holding the stock but doesn’t actually own it.

Gift tax: An individual can give only so much to someone else without paying taxes on the value of the gift. It’s meant to discourage people from avoiding estate taxes by passing on assets during their lifetime. The current lifetime maximum is $5.12 million.