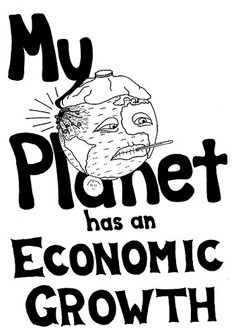

The ever-more-fashionable idea that we should desire and organize shrinkage in the economy to fight against the destruction it generates may seem a priori totally idiotic: how can anyone want to institutionalize depression, the consequences of which the whole world is suffering today in terms of unemployment and poverty? How can anyone desire a drop in production, that is, in average income, while the most elementary needs of developed countries’ populations have not been satisfied, let alone those of the billions of people who still live in extreme destitution? How can one desire negative growth when so much progress is heralded, creating hope for the possibility of ridding humanity of tiresome jobs, suffering, ignorance and pollution? Finally, how can anyone think that zero or negative growth would improve the environmental situation, while it’s not growth that pollutes, but production, the content of which is not improved by its stagnation?

See also: Favilla | Negative Growth?

Guillaume Duval | A Sustainable Economy? We’re Not There Yet …

Nonetheless, the idea makes sense: if one understands it as a desire to put an end to the vagaries of our model of production, to the insanities and fatigues of speed, “performance,” waste, accumulation, the ill-considered replacement of gadgets with other gadgets; and, above all, if one understands it as the determination to reconsider the commercial definition of greater welfare, of being better off.

In order to effect such a transformation, however, negative growth in the strict sense of the term is not what the world needs. Nor even is a different growth which would not change anything in the structure of production. But rather, a radical change in the very nature of the material goods produced and of their relationship to the times, to awareness and to feelings.

Such a metamorphosis, which should lead to adequate growth (hence the neologism “adequagrowth”) would require thinking of the social system as being in the service of the best use of time, including noncommercial time; constructing a system of production unceasingly adapted to new knowledge about resource conservation; imagining a health system based on prevention, even noncommercial prevention, rather than on care, costly in itself; implementing continuously improving governance to take people’s long-term desires and preferences into account. Then, the economy would end up leaving much more room for the production and exchange of free immaterial goods, from knowledge to art; and the market would have to content itself with assuring the infrastructure for that, specifically through the production of goods that satisfy basic needs.

This transformation will require enormous investments, which will – for a long time – translate into strong growth in material production that will have become adequate, that is, ever more economical of energy and careful to preserve the environment, turned toward immaterial achievements, acts of freedom and altruism, spirituality and fullness. That development will give its full value to time lived and no longer to forced time. One day, it will, perhaps, make us forget the very idea of growth, to replace it with the idea of fulfillment.

Translation: Truthout French Language Editor Leslie Thatcher.

==========

Negative Growth?

by: Favilla, Les Echos

Thursday 17 December 2009

A theme haunts the debate on safeguarding the climate, that of “negative growth.” One of the protesters demonstrating at the Copenhagen countersummit cited by Le Monde expressed it this way: “Infinite growth is not possible in a finite world.” An apparently obvious fact which deserves reflection. To reduce greenhouse gas emissions – by 20 percent to 30 percent in 2020, as the European Union has committed to do, by as much as 80 percent in 2050, as mentioned by Barack Obama – there exist, roughly, three ways. The first is to reduce economic activity; the second is to lower the “energy intensity” of that activity by replacing modes of production as well as good and services that emit high quantities of greenhouse gases (buildings, appliances, transports …); the third is to substitute “clean” and renewable energies for polluting energies.

The first of these alternatives is a synonym for negative growth and implies a massive decline in life styles. The two others will be implemented precisely to avoid that unacceptable scenario – and both involve pursuit of growth. First of all, because the substitution of new for old will necessitate research, job and working hour expenditures that national accounting will very classically assign to gross domestic product. But also, and above all, because our very conception of growth is in the process of changing. As the Stiglitz commission report on the measurement of economic performance emphasizes, taking into account “negative externalities” modifies our view of the past: if we deduct the (negative) value of the greenhouse gas emissions they gave rise to form the value of goods produced, we shall have to make steep downward corrections to the growth rates of preceding decades. Inversely, an activity that removes a source of pollution (for example, by making a residential building energy self-sufficient) represents a positive value exceeding its monetary appraisal: we would have to talk about “reparatory growth.” Simply a question of vocabulary, will some say? Not solely: the way the issue of the next battle is presented is not without influence on the morale of the troops.

Translation: Truthout French Language Editor Leslie Thatcher.

================

A Sustainable Economy? We’re Not There Yet …

by: Guillaume Duval, Alternatives Economiques

December 2009

Can the economy become sustainable? We’re very far from it at the moment and our ability to achieve that condition before humanity crashes into the consequences of the ecological disasters it has generated seems highly uncertain. That reflects the technical difficulty of the thing – a real issue – less than the sociopolitical obstacles that oppose every rapid and substantial reorientation in our modes of production and consumption. For the actions that must be conducted are simultaneously expensive and have a very strong impact on the distribution of wealth and social position. Wherewithal to clash with powerful interests and challenge many established positions. In other words, reducing the inequalities in the world as well as within our societies is both a condition for beginning the necessary reorientations, and, at the same time, a condition for obtaining results commensurate to the scale and bearing of the issue.

The Tools Available

The ecological perils that have accumulated since the beginnings of the industrial era are colossal. In the context of the Copenhagen conference, there is presently much question of climate change and the means to limit it. And that’s totally to be expected: it is undeniably one of the most consequential and simultaneously difficult-to-address threats, since any effective battle must absolutely be global. However, climate is unfortunately very far from being the sole problem: shortages of fresh water, deterioration of soils, losses of biodiversity, the accumulation of toxic wastes in our environment and in our food chain … we have but an embarrassment of choice, even as growth in global population, even though significantly slowing, should continue through the middle of the century – unless there’s a war or health catastrophe, neither totally unlikely in the present context.

Yet, to a great extent we know what must be done. First of all, rapidly and massively reduce the use of fossil fuels and non-renewable raw materials. Energy production, transportation, building insulation … we have already mastered many techniques to succeed. Already 15 years ago, a Club of Rome report entitled “Factor 4” enumerated all the technologies that would allow energy consumption to be divided by four, even while offering the same services in the end. Furthermore, one of its authors, Amory Lovins, of the Rocky Mountain Institute in the United States, explained that originally that report was supposed to have been called “Factor 10,” but that he had decided to declare “only” Factor 4 so as not to scare away the incredulous … We also know that if we were to devote a major research and development effort to these issues, at the expense, for example, of the one devoted to weapons of mass destruction, we would be able to rapidly expand the field of possibilities.

Beyond technologies strictly speaking, we also know in what direction we would have to reorient the productive system and modes of consumption. We would have to take the path of what is called “industrial ecology” or “circular economy”: as is the case in nature, the production processes that we organize must no longer produce waste, but constituent products to be reused in other production processes. The idea is simple and very old, but remains easier to expound than to implement. Notably because it involves a very costly change in what economists call “transaction costs”: in order for someone to use the sulfur recovered from factory chimneys, he first needs to be apprised that the sulfur exists, to negotiate a price for it, timetables for delivery etc.

We also need to move toward a “functional economy”: today we waste a great deal because it is in producers’ interest to have us acquire goods that are not very durable and to lead us to buy new ones as soon as possible. If they rented us services instead of selling us goods, it would be in their interest to use durable, energy-conserving products that are easily repaired in order to make their services profitable. But, there also, the passage from one system to another would inevitably shake up the structure of what’s offered as well as habits of consumption. All you need to be convinced that that’s the case is to observe the problems systems of self-service car-sharing that people are trying to develop today, such as Autolib in Paris, encounter.

Finally, we know what public policy tools must be implemented to bring economic actors, manufacturers, consumers to change their behavior. And without necessarily giving up the many advantages a market economy offers with respect to decentralization and individual freedom as much at the level of producers as of consumers. With prohibitions, labeling, norms, taxes, emission permits … governments, in fact, have available a whole panoply of tools, already well mastered, to reorient the economy.

Inequalities at Issue

If the problem is neither really on the technical side nor even in the structure of the economic system, where is it situated? For over 20 years now, we’ve known that the environmental wall was approaching at high speed. So, why then do we remain as though paralyzed, incapable of beginning the demonstrably necessary transformations? It’s because, as is often the case, the most complicated question to resolve is that of the relations between human beings themselves. In a democratic context, political leaders need to be re-elected every four or five years. Yet, most of the measures to be taken to confront ecological imbalances have the character of investments: they are costly in the short term – preventing other public expenditures or drastically cutting citizens’ resources – and “pay back” in the long term only if, in two or three generations, we’ve succeeded in avoiding environmental catastrophe.

The result is that politicians, even when they are convinced of the stakes, have a lot of trouble getting the necessary measures adopted: there’s always a political adversary who will surf the discontent the proposed measures inevitably arouse. In spite of the Environment Summit and bipartisan consensus that seemed to take shape around these issues, we’ve just had a good example in France, with the political storm raised by the proposed carbon tax, even though it was quite minimal! This difficulty, intrinsic to democratic politics, is obviously multiplied on the international level by the absence of global governance and the bonus that gives free riders: on these problems which rarely respect country borders, one may often be a winner if others do the work without participating in the collective effort oneself.

But what makes these problems of political technique insurmountable are the fantastic inequalities that exist within each society and even more on the global level. The costly measures that must be taken have, in general, the effect of threatening – in relative terms – the incomes of the poorest more, both on the level of each society and on a global level. Nonetheless, at the level of each society, it is incontestably the rich who waste the most. To make things still more difficult, their conspicuous consumption also feeds the dynamic of waste by everyone else. Similarly, on a global level, the richest countries bear the greatest responsibility for the deplorable state of the planet, given the damage caused by two centuries of uncontrolled development.

In other words, the ecological problem may be solved only in the framework of a vast policy of wealth redistribution within each society and on a global level. But history shows that the upper crust never willingly agrees to have its position contested.

Waiting for Pearl Harbor

Will we ever succeed in overcoming these – human – obstacles in time? It’s not certain. But to conclude on a more optimistic note, let’s take up the analogy used by Lester Brown, one of the pioneers of ecology in the United States. The present period reminds him of the long and difficult discussions Americans had before entering the Second World War. And for perfectly comprehensible reasons, when one measures the sacrifices that ensued … And then there was Pearl Harbor. Afterward, and all the while remaining a democracy, the country mobilized entirely for the war effort: not a single individual automobile was manufactured for four years. Consequently, the present period may be only the long – and frustrating – period of inevitable maturation to discover the basis for an acceptable consensus in order to set off the effort necessary within societies as well as on a global level. If that’s the case, we may only hope that the environmental Pearl Harbor that will (finally) make us decide to act not be too dramatic …

They Said

Jean-Baptiste Say: “Natural wealth is inexhaustible; otherwise, we wouldn’t get it for free. Neither increasable, nor exhaustible, it is not the object of the economic sciences.”

Chateaubriand: “Forests precede people, deserts follow them.”

Gandhi: “The world contains enough for each person’s needs, but not enough for everyone’s greed.”

Anatole France: “It is human nature to think wisely and behave absurdly.”

Albert Camus: “It will be necessary to chose, in the more or less near future, between collective suicide and the intelligent use of scientific conquests.”

Dennis L. Meadows: “Humanity has lost thirty years. Had we begun to construct alternatives to material growth in the 1970s, we could regard the future in a more relaxed way.”

Herman Daly: “Adam Smith’s invisible hand has mutated into an invisible foot, kicking nature and society into pieces.”

Michel Serres: “If we make the bet of being environmentally imprudent and the future proves us right, we win nothing but the bet and we lose everything if the bet is lost; if we make the bet of being prudent and we lose that bet, we don’t lose anything, and if we win that bet, we win everything.”

Larry Summers: “Underpopulated countries in Africa are vastly underpolluted, their air quality is probably vastly inefficiently low compared to Los Angeles or Mexico City (…) shouldn’t the World Bank be encouraging MORE migration of the dirty industries to the LDCs [Less Developed Countries]?”

Translation: Truthout French Language Editor Leslie Thatcher.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.